Self, Psyche and Symbolism in the Roman de la Rose

by

Amy Kincaid Todey

May 1, 2012

It is a long-held belief in psychology that insight into the unconscious contributes to therapeutic relief. Similarly, it is widely thought that the resolution of internal conflicts promotes good psychological health. The present study of the medieval, illuminated manuscript the Roman de la Rose, demonstrates how life themes can be understood through psychodynamic analysis of symbols found in allegory and art. From a theoretical standpoint, this inquiry performs a Jungian analysis of four symbols of the human self that are embedded in the mythology and art of the Roman de la Rose: the dream, the mirror, the Pool of Narcissus and Pygmalion’s sculpture. This inquiry also reveals the presence of the Jungian archetypes of the anima, the animus, the self and the shadow that are evoked by the Roman de la Rose symbolism. The implications and impact of these Jungian archetypes are discussed as they relate to the integrity of the Roman de la Rose manuscript and expand traditional interpretations of Roman de la Rose symbolism to include the psychodynamic perspective.

Self, Psyche and Symbolism in the Roman de la Rose

The medieval mind understood the world largely through making sense of the symbols of the surrounding environment. In medieval culture, as reflected in the customs, literature, and art of the time, commonplace objects such as animals and plants were imbued with moral significance derived from their distinctive behaviors and physical traits. Through the interpretation of the natural environment by way of this familiar symbolic code, medieval men and women sought spiritual connectedness and insight into the human psyche. The medieval use of symbols to attain self-insight may be considered primitive and unscientific by modern terms. However, this practice reflects a profound, forward-thinking curiosity about the nature of the human psyche that did not completely emerge until the birth of psychology in the late nineteenth century.

Borrowing from the symbolic tradition of the Middle Ages, the Roman de la Rose, originally written by Guillaume de Lorris (circa 1235) and expanded by Jean de Meun (circa 1270), is an illuminated allegory that encompasses a wide range of medieval values, beliefs, and perspectives that contributed to the psychology of 13th Century France. The poem tells the story of a Lover who falls asleep and, while dreaming, stumbles upon a walled garden. The Lover is intrigued by the garden despite the plethora of hostile images embedded in its walls: personified vices including representations of hate (“Haïne”), violence (“Felonie”), abuse (“Vilanie”), greed (“Convoitise”) and misery (“Tristesce”). The Lover seeks and is eventually offered entry to the garden by Oiseuse (“Ease”/”Leisure”), the garden’s protector.

Once inside, the Lover encounters “Deduiz”, or “pleasure” who is accompanied by personifications of courtly virtues such as friendship (“Amis”), openness (“Franchise”) and reason (“Reson”). The Lover then stumbles upon the mythical Pool of Narcissus which contains crystals that reflect the contents of the garden, including several rosebushes. As the Lover looks into the pool, Venus shoots him with an arrow, causing him to fall in love with one particular rose. In Jean de Meun’s continuation, the Lover boldly and deceptively plucks the rose from the rose bush provoking a series of debates between personified virtues on the inside of the garden, and personified vices contained on the garden wall. The end of the poem contains a retelling of the Pygmalion myth, in which Pygmalion carves a statue of a woman, falls in love with it and prays to Venus to bring the statue to life. (de Lorris & de Meun, trans. 1974).

While the plot of the Roman de la Rose provides ostensible narrative structure, the manuscript’s deeper meaning derives largely from the profusion of symbolism, imagery and myth that it contains. The text and accompanying illuminations present a plethora of reemerging symbolic themes such as the dream, the journey, the walled garden, mythical beings, mirrors, references to alchemy and various personifications of psychological and emotional concepts commonly found in medieval literature and art. This medieval orientation toward symbolism, as reflected in the Roman de la Rose, fascinated psychodynamic theorist Carl Jung who similarly believed that unconscious symbols are projected, reflected and interpreted through dreams, art and myth. The understanding and interpretation of psychodynamic symbols comprised a major portion of Jungian theory of individual personality development and cumulative evolution of the human psyche (i.e. collective unconscious).

Despite the convergence of Jungian philosophy with the medieval symbolism contained in the Roman de la Rose, the poem’s psychodynamic themes have been largely neglected by traditional literary analyses. Further, psychological and literary critics of analytical psychology contend that Jung’s theoretical contributions to the understanding of human psychology have in fact been rendered archaic and obsolete by advances in modern neuroscience and biology. Nevertheless, research in behavioral biology, anthropology, evolutionary psychiatry, developmental psychology and psycholinguistics has provided cross-disciplinary empirical corroboration for aspects of Jungian theory such as archetypes, the collective unconscious and the psychological salience of dreams and myth (Haule, 2011; Stevens, 1995). This evidence points to the timeless and universal themes present in Jungian theory that indicate a confluence between spirituality, literature, psychology and modern science which Jung intuited long before the availability of the technological and scientific methods requisite for empirical investigation. The purpose of the present inquiry is therefore to identify the presence of Jungian symbolism in the Roman de la Rose and to discuss its significance in advancing understanding of the human psyche. To this end, this study will discuss how the allegory, myth and art of the Roman de la Rose lend to the projection of unconscious symbolism, provide analyses of psychodynamic symbols in the text and accompanying illuminated miniatures[1], and describe how psychodynamic symbols serve to enhance the integrity and unity of the combined Guillaume de Lorris and Jean de Meun Roman de la Rose manuscript.

Allegory, Myth and Illuminations of the Roman de la Rose

The monolithic importance and widespread influence of the Roman de la Rose is self-evident in its extensive manuscript tradition. Today, 310 whole or fragmentary Roman de la Rose manuscripts remain of which 230 are fully or partially illuminated. The present study concentrates on the particular collection of Roman de la Rose manuscripts referred to as the Aberystwyth Collection[2] preserved in the National Library of Wales. This collection of manuscripts has been described by scholars as exemplary in that its illuminations are neither outstanding nor idiosyncratic (Blamires & Holian, 2002). Given the wide range of illumination styles that exist for the Roman de la Rose, mainstream illuminations, such as those contained in the Aberystwyth collection, are most representative, most widely generalizable, and hence most appropriate as targets of analysis.

Allegory and Myth

The Roman de la Rose is considered to be the seminal work of medieval allegory that inspired a proliferation of succeeding allegorical works (Blamires & Holian, 2002; Huot, 1993; Lewis, 1936). In the classic sense, an allegory is a story that uses fictional figures and symbolism to portray generalizations about human behavior, society and existence. The allegory of the Roman de la Rose is enhanced by the mythical references and recapitulations of mythical stories, such as those of Narcissus and Pygmalion, which it contains.

Literary and psychological scholars alike have recognized the usefulness of myth and allegory as a means of understanding human beings. For Carl Jung (1990a), artistic and linguistic human expression often embodies unconscious psychic projections. “It is with the hand that guides the crayon or brush, the foot that executes the dance step, with the eye and the ear, with the word and the thought: a dark impulse is the ultimate arbiter of the pattern, an unconscious a priori precipitates itself into plastic form…” (p. 76). Similarly, Roman de la Rose literary scholar, C. S. Lewis (1936) describes how allegory serves to “paint the inner world” of individuals by revealing the complex and often contradictory motives, feelings, values and behaviors that comprise the human psyche. He further attests to the power of allegory in unveiling important aspects of our psychological past: “We shall understand our present and perhaps even our future, the better if we can succeed, by an effort of the historical imagination, in reconstructing that long-lost state of mind for which the allegorical love poem was a natural mode of expression.” (p. 1).

Lewis’ acknowledgement that our psychological past serves as a blueprint for our present and future behavior parallels Jungian theory of the collective unconscious. Jung (1990a, 2001) believed that fairytales and myths are indispensable parts of our psychic anatomy passed to us at birth. Moreover, an understanding of the collective unconscious necessitates looking beyond the superficial meaning that authors intentionally ascribe to allegoric personifications to the natural, spontaneous and unconscious projection of the more esoteric symbols of unknown parts of the psyche. In this way, Jung therefore differentiates semiotic meaning from symbolic projections. For example, in traditional interpretations of the Roman de la Rose the rose appears to be intentionally used by the authors to signify a woman sought after by the Lover. In this interpretation, the rose is what Jung would term a “sign” or “an abbreviated designation for a known thing” that in this case is a woman (285). In contrast, a psychodynamic interpretation of the rose might suggest that it is a symbol of the anima, the internal female aspect or “soul” of the human psyche (282). In the latter case, the rose functions as a “symbol” because, as Jung states, it is “the best possible formulation of a relatively unknown thing”, the anima, “which for that reason cannot be more clearly or characteristically represented” (285). The anima symbol is indeed a mystical, intra-psychic concept of femininity to be differentiated from the tangible, intentional and external allegoric personification of the rose as a sign of a woman. While many literary critics have interpreted the semiotic meaning found in the personifications of the Roman de la Rose (Blamires & Holian, 2002; Gunn, 1952; Huot, 1993; Lewis, 1936), few have looked beyond traditional allegorical interpretations to uncover the deeper psychodynamic symbolism it contains.

Illuminated Manuscript

In addition to its allegorical and mythical qualities, the Roman de la Rose is also an illuminated manuscript, a written story accompanied by decorated page borders, ornate lettering and miniature illustrations. During the Middle Ages, manuscript illuminations functioned as artistic supplements to written dialogue intended to provide visual commentary to complement textual discourse. However, the illustrations accompanying the Roman de la Rose are more than simple replications of the textual account of the story. Roman de la Rose scholars Blamires and Holian (2002) point out that “The illumination of a manuscript both makes it bright and illustrates and throws light upon its meaning” (p. xxviii). This perspective suggests that analysis of Roman de la Rose illuminations in conjunction with the text is essential because it yields an interpretation that is much more lucrative than an analysis of textual content alone. This view furthermore parallels Jungian psychodynamic theory that art provides a powerful canvas for the projection of unconscious symbols.

Besides the benefit of the abundant interpretive material offered by the illuminations of the Roman de la Rose, the manner in which the manuscripts were reproduced also lends itself to psychodynamic analysis. Manuscript reproduction during the Middle Ages relied on arduous, primitive printing methods that were expensive and time-consuming. The resulting economics of medieval book selling engendered a process of manuscript illumination that was often a capricious, impulsive and unsystematic. Incidentally, in effort to keep down costs, scribes often budgeted slots for miniatures with only superficial consideration of the integrity of the written manuscript. For the Roman de la Rose, this practice created an unexpected interpretive benefit ideal for psychodynamic study. (Blamires & Holian, 2002). According to Jungian theory, the most powerful, profound and revealing symbols of the unconscious are projected in a spontaneous, accidental way. Jung (1990b) observed that

One cannot invent symbols; wherever they occur they have not been devised by conscious intention and willful selection, because, if such a procedure had been used, they would have been nothing but signs and abbreviations of conscious thoughts. Symbols occur to us spontaneously, as one can see in our dreams which are not invented but which happen to us (p. 70).

Psychic symbols are engendered on instinct, without premeditation, intention or conscious thought. The presence of a symbol therefore implies a degree of spontaneity and imprudence, consistent with the illustration methods of the Roman de la Rose. Accordingly, the perfunctory nature of the Roman de la Rose illustration process produced a model scaffold for the spontaneous projection of psychodynamic symbolism.

Symbols in the Roman de la Rose

Through illumination and allegory, the Roman de la Rose gives an account of courtly romance as experienced by a lover in a dream. Although historically critics have interpreted the Roman de la Rose as a description of the various challenges that young people face as they enter adulthood (Blamires & Holian, 2002), the poem contains a deeper psychological meaning. The unconscious symbolism in the Roman de la Rose--contained both in the text and in the Aberystwyth illuminations discussed in this paper-- disguises the true psychic nature of the Lover’s quest. The application of psychodynamic interpretation to the Roman de la Rose reveals the presence of unconscious dream symbolism that exposes the Lover’s implicit search for his self and renders a surprising unity to the work. While numerous psychodynamic symbols exist in the Roman de la Rose, the current analysis will focus on the symbolic significance of the dream, the mirror, the pool of Narcissus and the Pygmalion sculpture and discuss how these symbols contribute to and advance the Lover’s search for his self.

The Dream

The dream serves as the central construct for the Roman de la Rose as it establishes the framework upon which the subsequent events build. The poem begins with the Lover’s profession of faith in the wisdom and prophetic power of dream visions as he asserts that “dreams are oft times true” (De Lorris & De Meun, 1962). Jungian theory mirrors the medieval belief in the authority of dreams and the influence of dream symbolism infused throughout the Roman de la Rose. Incidentally, Jung (1990b) described dreams as the “commonest and universally accessible source for the investigation of man’s symbolizing faculty” and “…the chief source of all our knowledge about symbolism” (p. 70). In the Roman de la Rose, the psychological significance of the symbolism that appears in the Lover’s dream is reinforced by the inseparability of the allegorical account of the Dreamer from the possibility of the authors’ actual dream experience. Therefore, the unconscious projection of the self may occur on two levels: the self first is projected into the dream that, in turn, is projected into the illuminations and the allegory of the Roman de la Rose.

Jungian dream symbolism, such as that which is found in the Roman de la Rose, represents the subconscious search for the unification of the contrasting parts of the human self. Nature is composed of opposites such as light and dark or warm and cold. Moreover, as products of nature, human beings are also polarized. For example, the conscious self, which consists mostly of positive qualities, opposes the shadow, which contains the negative parts of the self that have been repressed. Likewise, the anima, which represents the feminine half of the human whole, opposes the animus, or the male half. Most human beings have difficulty integrating the split parts of the self and therefore repress basic human urges into the unconscious, where they fight for control of the psyche. The reconciliation of virtue and vice, the self and the shadow, and the anima with the animus serves as the central quest of human beings as they search for wholeness and meaning in their lives (Jung, 1958, 1964).

In the Roman de la Rose, the Lover’s dream state allows him to embark on a psychic quest for the self. Indeed, as the hero of the story, the Lover embodies the universal archetype of the self that is repeated across cultures in dreams, art, and myth. “Empirically, the self appears in dreams, myths, and fairytales in the figure of the ‘supraordinate personality’…, such as king, hero, prophet, saviour, etc.” (Jung, 2001, p. 275). As the Lover’s dream journey unravels, many other psychic symbols emerge offering powerful clues into the unconscious mind. In this way the Roman de la Rose itself, with its narrative presentation of a journey embedded in a dream vision, can be viewed as an archetype of the universal human quest for psychic unity.

The Mirror

The prevalence of the search for the self in the Roman de la Rose manifests the symbolic representation of the mirror as the central theme of the work. Traditionally scholars have interpreted the mirror in the Roman de la Rose as a symbol of the cultivation of beauty or of lust relating to the Garden of Pleasure (Blamires & Holian, 2002). However, setting the mirror within a larger psychodynamic context of the poem casts light on a deeper, unconscious significance. The mirror has projective qualities that make it possible to simulate the image of the human face and displace it onto inanimate material. In the Roman de la Rose, the mirror not only projects the Lover’s physical traits, it also symbolically projects the innermost repressed urges of the Lover’s unconscious onto the objects and archetypes in the garden. In this way, the mirror serves as the medium that gives the Lover access to his unconscious through his dream.

The mirror symbol appears many times in the Roman de la Rose, functioning as a vehicle that offers the Lover increasing access into the layers of his unconscious mind. In Jung’s (2001) view, as in the Roman de la Rose, the mirror symbol is inextricably linked with the symbol of water, in that both possess reflective properties and signify the discovery of the unconscious.

True, whoever looks into the mirror of the water will see first of all his own face. Whoever goes to himself risks a confrontation with himself. The mirror does not flatter, it faithfully shows whatever looks into it, namely, the face we never show to the world because we cover it with the persona, the mask of the actor. But the mirror lies behind the mask and shows the true face (316).

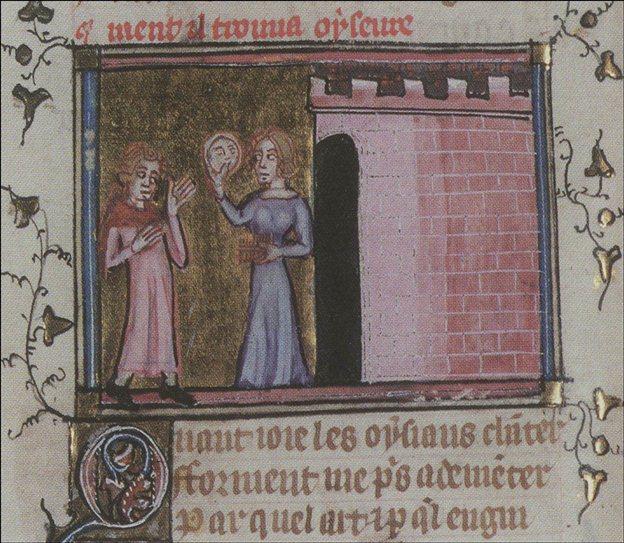

In the Roman de la Rose, the Lover’s access to his unconscious self through the mirror is foreshadowed by the symbolic act of washing his hands in a reflective basin at the beginning of the poem immediately before he enters his dream. The mirror symbol reappears (Figure A1) when the Lover encounters Oiseuse who is holding a mirror at the gateway of a walled garden, a psychodynamic symbol for the unconscious (Jung, 2001). Once inside the garden, the Lover then stumbles upon the Pool of Narcissus (Figure A2), a quintessential mythical mirror symbol, in which he sees the reflection of his face and the contents of the garden, including the rose. Finally, the presence of the mirror symbol culminates with Pygmalion’s sculpting of a female form (Figure A3), a mirror image of himself, at the end of the poem.

The Lover’s encounter with Oiseuse at the gateway of the Garden of Pleasure is the first scene in which the mirror appears explicitly and is clearly used to propel the events of the poem. The Aberystwyth illumination (Figure A1) illustrates the predominance of the mirror in the scene (Blamires & Holian, Plate 29). The mirror appears to be the point of focus of the image as it is stands out from the neutral background of the wall. Its color and design compared to the muted background draw attention to it. In addition, the Lover raises his arm toward the mirror, a gesture that underscores its importance.

The concentration on the mirror in the illumination is curious in that it contrasts greatly with its description in the text. In the poem, the mirror appears as one element of a much larger description of Oiseuse’s elegance. In a fifty line account of her beauty, the description of the mirror requires only six words. “En sa main tint un mireor” (de Lorris & de Meun, 1974, p. 57). Outwardly, the poet’s use of the mirror to denote Oiseuse’s magnificence seems superfluous in light of the verbose textual depiction. Further, the disproportionate weight placed on the mirror in the illumination suggests that it contains a value that extends well beyond its function as a symbol of beauty. In contrast to the traditional interpretation that gives limited insight into the mirror’s meaning, psychodynamic analysis of the scene seems to reveal that Oiseuse’s mirror represents access to parts of the unconscious mind that can only be seen if projected onto other people and objects in the surrounding environment. Indeed, it is directly following his encounter with the mirror that the Lover begins his journey that, from a psychodynamic perspective, appears to lead him into his personal unconscious, symbolized by the Garden of Pleasure, and eventuates in his symbolic discovery of the collective unconscious, symbolized by the Pool of Narcissus.

The illumination (Figure A1) of the Lover’s entrance into the Garden of Pleasure appears to represent the symbolic manifestation of the missing half of the Lover’s self that he seeks. One possible way to discern the psychodynamic symbolism of the Figure A1 illustration is to understand the inherent balance achieved through the duplication and completion of the archetypal figures represented in the scene. Following this interpretation, the Lover, represented at left, is followed by his reflection in the mirror that Oiseuse holds. This animus double is succeeded in the image by the archetype of the anima, Oiseuse, who stands near the obscure opening to the Garden. The image suggests that the Lover recognizes his animus--his male self reflected in the mirror--but must enter his unconscious through the garden gate to find his anima – his female half or “soul”. The Lover’s recognition of his feminine half would complete the illumination and make the Lover whole. This evidence establishes the role of the mirror as a mechanism that allows the Lover access to new vision and perspectives of his self.

In addition to the achievement of anima-animus unity through the balancing of female-male archetypes in the Figure A1 illumination, the Jungian theme of unity is also strengthened by an analysis of the reflection of the face in the mirror that Oiseuse holds. According to Blamires and Holian (2002), it is difficult to determine from the image if the Lover is gazing at Oiseuese or at the mirror itself (65-66). Indeed, both the Lover and Oiseuse seem to direct their gaze into it. In addition, both seem to acknowledge it’s magnitude in the scene. Oiseuse presents the mirror to the Lover who confirms its importance by pointing toward it. One possible psychodynamic interpretation of this illumination would be that the image in the mirror belongs to the Lover and that the scene foreshadows the Lover’s eventual discovery of his self in the Pool of Narcissus later in the story. As the gatekeeper, Oiseuse could be using the mirror to foretell what the Lover would unveil on the inside of the garden, namely his unconscious mind.

However, the image in the mirror seems intentionally ambiguous. There are no characteristics that stand out in any way: there is no hair on the face, the eyes are closed and there is no colored clothing reflected in the mirror. The hermaphroditic qualities of the face replicated in the mirror hold a certain psychodynamic wisdom in that they correspond to Jung’s belief that human beings possess both male and female parts. Further, the notion of material ambiguity makes up a significant part of alchemic beliefs in the uniformity of substance that are salient both in the Roman de la Rose and in Jungian philosophy. Jungian analyst and scholar Nathan Schwartz-Salant (1995) asserts that “In the alchemical tradition, the world is comprised of a prime matter with only the potential for existence. To be manifest, it had to be impressed by ‘form’. This meant not only shape but “something that gave a body specific properties” (p. 12). Just as nature projects images and ideas onto neutral matter as Schwartz-Salant (1995) describes, in the Roman de la Rose, the projections of the anima (Oiseuse) and the animus (the Lover) in the mirror combine to create a completed being devoid of the disparate male and female characteristics that humans typically possess. Although the Lover does not appear to attain full unification with his anima in this scene, the potential of becoming whole predicted by the androgynous reflection in the mirror seems to draw him into the Garden of Pleasure where he could symbolically continue his psychic journey. In the scene illuminated in Figure A1, the mirror therefore appears to offer the Lover the opportunity to explore the garden of his unconscious where he may have the potential to reconcile the incongruent aspects of his psyche. Oiseuse’s mirror not only foreshadows the unification of the Lover’s male and female self, it also seems to echo the self-recognition of the authors, illustrators and readers as they follow the Lover on his journey into the unconscious. The indistinct characteristics of the mirror image render it adaptable to any face that gazes into it. Furthermore, it is turned flat and angled forward toward the audience. This gesture suggests an effort, whether conscious or unconscious, on the part of the manuscript illuminators of The Roman de la Rose to find their own selves and to invite readers to begin their own personal self-seeking journeys. In accordance with Jung’s philosophy, human beings involuntarily project repressed urges onto archetypes that appear in dreams and art. The symbol of the mirror in this illumination empowers the readers and the authors to project aspects of their selves to the archetypal personages of the illumination.

The Pool of Narcissus

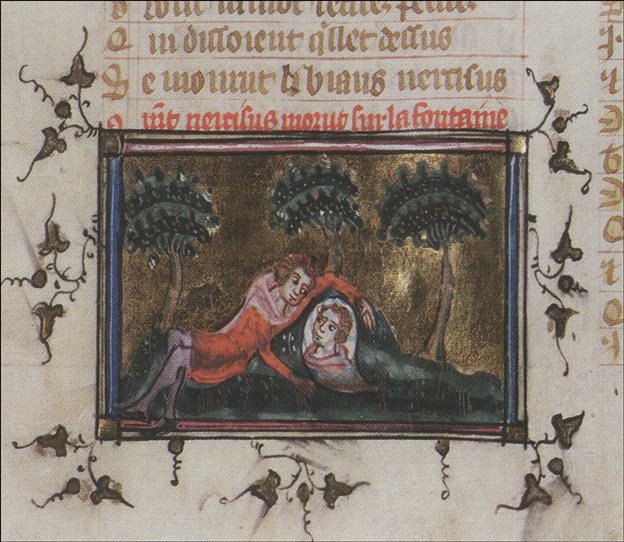

The Lover’s knowledge of his psyche expands as he enters the garden and encounters a reflection of his collective unconscious in the mythical Pool of Narcissus (Figure A2). The journey of the Lover to the pool and his psychological descent into its depths parallels a universal human dream quest to understand the unconscious, described in symbolic terms by Carl Jung (2001). “Therefore the way of the soul in search of its lost father…leads to the water, to the dark mirror that reposes at its bottom…This water is no figure of speech, but a living symbol of the dark psyche” (313). The Lover’s encounter with the pool of Narcissus is therefore a recapitulation of a common archetypal dream which Jung views as symbolic of a spiritual awakening, or healing. To illustrate, Jung (2001) references the pool of Bethesda, a biblical pool that possessed healing powers whenever an angel miraculously touched its waters. The divine intervention that occurred at the pool of Bethesda is reflected in the Roman de la Rose as Venus shoots the Lover with arrows, causing him to fall in love with the rose, or, in psychodynamic terms to encounter his anima, a symbol of the feminine aspect or soul of the psyche. As Jung (2001) states, “Man’s descent to the water is needed in order to evoke the miracle of coming to life” (313). By descending psychologically into the Pool of Narcissus, the Lover appears to gain deeper access to the spiritual realm of his unconscious, leading him to a greater level of psychic unity and spiritual congruence.

Evidence of the psychodynamic symbolism of the Pool of Narcissus and its ability to transport the Lover to a deeper unconscious level is furthermore demonstrated by the Lover’s re-experiencing of the Garden of Pleasure through the reflections he sees in the pool. Before the Lover finds the pool and sees the contents of the garden through it, the text states that he had already thoroughly explored all the parts of the garden.

Well on I went, turning first right then left,

Till I had searched out and beheld each sight –

Experienced each charm that the place possessed

(De Lorris, G. & de Meun, J., 1962, 29).

Despite the Lover’s prior acquaintance with the contents of the garden, as the he gazes into the Pool of Narcissus he experiences them in a new way as they are reflected in the two crystals at the bottom of the pool. In fact, the text states that, when illuminated by the sun, the crystals have the power to transform the contents of the garden.

Two crystal stones within the fountain’s depths

Attentively I noted. You will say

‘Twas marvelous when I shall tell you why:

Whene’er the searching sun lets fall it’s rays

Into the fountain and it’s depths they reach,

Then the crystal stones there do appear

More than a hundred hues; for they become

Yellow and red and blue. So wonderful

Are they that by their power is all the place –

Flowers and trees – whate’er the garden holds –

Transfigured as it seems… (De Lorris, G. &

de Meun, J., 1962, 31 – 32)

From a psychodynamic perspective, the crystals in the Pool of Narcissus possess the power to uncover repressed parts of the Lover’s psyche, symbolized by the objects in the garden. The text specifies that there is nothing in the garden can hide from the illuminative power of the stones. It is indeed by way of the Pool of Narcissus, that the Lover discovers his shadow--or the competing vices that fight for control of his psyche--as well as his anima represented by the rose. The shadow and the anima are parts of the self that are typically obscured from human consciousness which explains why the Lover couldn’t clearly see them until he was allowed access to the collective unconscious through the Pool. Even still, despite the clarity that the crystals offer, they only reveal one half of the garden at a time which seems to illustrate the Lover’s struggle to integrate the opposing aspects of his self.

So do these crystals undistorted show

The garden’s each detail to anyone

Who looks into the waters of the spring.

For, from whichever side one chance to look,

He sees one half the garden; if he turn

And from the other gaze he sees the rest.

So there is nothing in the place so small

Or so enclosed and hid but that it shows

As if portrayed upon the crystal stones

(De Lorris, G. & de Meun, J., 1962)

The textual description of the scene in which the Lover discovers the Pool of Narcissus includes details of the garden that are illuminated by the reflection of the sun’s rays off the crystals in the pool. However, the illustration of the scene (Figure A2) diverges largely from the textual account. In the illumination, the Lover gazes into the pool and a face is reflected back to him. The illustration does not account for either the mysterious contents of the garden that were described in the poem or the crystals that play such an important role in the scene. Interpreted together from a psychodynamic perspective, the text and the illumination appear to indicate that the Lover sees a deep reflection of his psychic self in the pool, a reflection that contains not only his physical traits and consciousness, but also the repressed and archaic components of his unconscious disguised in the symbols generated by his dream. As the Lover looks into the Pool of Narcissus he sees a profound reflection of his psyche that is pushed so deeply into the cavities of his unconscious mind that he recognizes it only in the deep, cryptic layers of his dream.

As the Lover’s conscious self comes to know its unconscious, the balance that was foreshadowed at the gateway of the garden is achieved. The animus gazes into the pool of the collective unconscious and discovers its anima, symbolized by the rose, which is reflected back to it. The union of the animus and the anima in the scene represents the symbolic completion of the missing part of the Lover’s self. Likewise, in the depths of his unconscious, the Lover witnesses the internal battle of his conscious self with his repressed fears and collective human vices such as Jealousy, Hate, Sadness, Poverty and Old Age. Through the Pool of Narcissus the Lover recognizes and acknowledges the disparate parts of his psyche: male and female, virtue and vice. This reunion of the Lover’s self with his shadow and his animus with his anima, produces a whole, congruent, natural being.

Pygmalion

The psychic unification of the Lover that is enacted in the Pool of Narcissus culminates with Jean de Meun’s recapitulation of Ovid’s story of Pygmalion which is included at the end of the Roman de la Rose. Roman de la Rose scholar Alan Gunn (1952) observes that the Pygmalion story serves as a parallel to and an underscoring of the Lover’s pursuit of the rose and “affirms the meaning and end of the quest” (289 – 290). Through a psychodynamic lens, the entelechy that is made evident with the insertion of the Pygmalion myth into the poem brings to light the symbolic unification of the Lover’s anima and animus and reinforces the psychodynamic themes of self-creation, recognition and projection as central to the meaning of the poem.

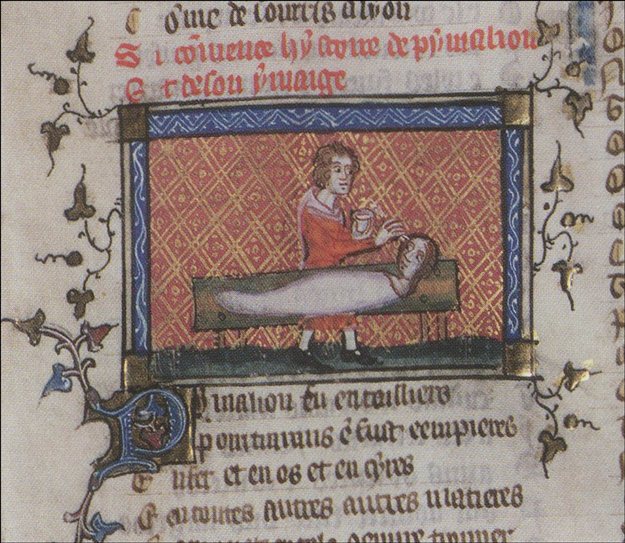

Pygmalion was a sculptor who carved an ivory sculpture of a woman who he found to be so beautiful that she could not be rivaled by any living being. He admired his sculpture so much that he fell in love with it and prayed to Venus to bring the statue to life. Although many Roman de la Rose scholars (Huot, 1993; Lewis, 1951) regard the Pygmalion passage with disdain and see it as contributing to the nonsensical, digressional style of Jean de Meun, from a psychodynamic perspective the Pygmalion scene seems complementary and, in fact, essential to the integrity of the completed allegory. The Pygmalion story, as retold by Jean de Meun, and the associated Aberystwyth illumination of the Pygmalion scene (Figure A3) once more evoke the concept of Alchemy that is thematically interwoven throughout Jungian theory and in the passages and illuminations of the Roman de la Rose. Indeed, Pygmalion fell in love with his own creation, an unconscious self-projection that spontaneously transformed the neutral matter of ivory into a sculpted figure of his anima. Stated another way, Pygmalion succeeded in giving ‘form’ to his soul, in the same way that Alchemists endeavored to create gold, the ideal, perfect metal, by the melting and combining of other metals such as copper, iron, mercury and lead. Jung’s perspective on Alchemy includes the assertion that human beings project soul onto matter. “The alchemists were fascinated by the soul of matter which, unknown to them it had received from the human psyche by way of projection” (Jung, 1995, 71). Interpreted in this way, Pygmalion’s drive to find his anima reveals his need to achieve wholeness by the unification of his masculine and feminine halves.

In addition to the anima-animus unification in the Pygmalion story that was made possible through Alchemy, the triadic change process that eventuates in the magical resurrection of Pygmalion’s statue also parallels the fundamental alchemical principal of transformation, known as the ‘Axiom of Ostanes’. Alchemists conceptualized change in terms of the union of different types of matter through a specific three phase transformational process: “A nature is delighted by another nature, a nature conquers another nature, a nature dominates another nature” (Schwartz-Salant, 1995, p. 8). This formula can be applied to the mutual process of change that Pygmalion and his statue experience. Pygmalion carves a statue and pledges his love to it. This reminds us of the first part of the axiom: “Nature is delighted by another nature”. Although Pygmalion’s love pledge can be conceived of as a union, this union state must overcome the fact that the statue is lifeless requiring another union with Venus and a new nature for the statue thus evoking the second part of the axiom: “A nature conquers another nature”. Finally, Pygmalion and his living statue unite as one demonstrated initially by an exchange of vows and culminating with their conception of a son. This final step can be seen as Pygmalion becoming one with his creation through another union in which “A nature dominates another nature”. Thus, for Pygmalion, his sculpting of his statue was much more than a mere technical act of carving. Through an artistic, alchemic process of creation, Pygmalion gave life to an inanimate object and both of them became part of a greater psycho-physical unity. In this way, the Pygmalion story reinforces Narcissus’ search for self evoked at the beginning of the Lover’s quest and parallels the dream-journey of the Lover through the garden of his unconscious. The mythological stories of Narcissus and Pygmalion therefore frame the Lover’s narrative in classical, mythological bookends, illustrating the spontaneous and universal repetition of archetypal figures that Jung describes through his theory of the collective unconscious. Consequently, in the Roman de la Rose, Narcissus, Pygmalion, and the Lover are essentially the same being, representative of the universal archetype of the self on its journey toward wholeness and integrity.

To take this interpretation further, Leusheuis (2006) has concluded that through Jean de Meun’s retelling of the Pygmalion myth, he poses Pygmalion as a symbolic reflection of himself, and therefore advances a form of himself as the ultimate protagonist. In this view, the alchemic, life-giving transformation of matter would occur on two levels: Pygmalion gives life to his statue as the author gives life to his words. Leusheuis (2006) furthermore contends that the Pygmalion story brings to light an important intersection between the story’s plot and the technical aspects of writing and language. According to him, it is only through sexual cooperation between the male author-artist (Jean) and the female divinity (Venus) that a soul can be given to Pygmalion’s lifeless statue. This interpretation has obvious alchemic significance and also provides further evidence to support the theoretical line of reasoning embraced by the present study by revealing the Roman de la Rose itself as an archetypal symbol of the universal human journey toward androgyny, wholeness, and ultimately self-recognition.

In addition, the view of Pygmalion as an embodiment of the author again evokes the three stages of the alchemic act as previously discussed. Jean de Meun encounters the story of Pygmalion and is delighted by it. He then projects himself into it as a dynamic factor that attributes new qualitative meaning to the myth, thus changing the original meaning. Finally, through the union of himself with the material of the story, Jean dominates the matter of the story, takes it into himself and a new spiritual space is therefore created.

In addition to the literary interpretation of the Pygmalion story that provides evidence of psychodynamic meaning, psycho-symbolic material can also be gleaned from a close analysis of the Aberystwyth illumination that accompanies the Pygmalion passage. The miniature that accompanies the Pygmalion story (Figure A3) portrays a sculptor working on a recumbent female form. However, in contrast to the chisel and hammer that would be expected tools of a sculptor, the Pygmalion in this illumination is equipped with a vessel and a brush. The use of such delicate tools has been interpreted by Blamires and Holian (2002) as indicative of “the elaborate attention Pygmalion is to pay to dressing and ornamenting his creation” (p.101). However, in addition to this interpretation, a psychodynamic perspective suggests that the vessel that Pygmalion holds implies a chemical transformation reflective of early forms of chemistry practiced by alchemists. Beyond the illustration of Pygmalion’s tools, other hints of alchemy exist in the illumination. For example, the statue being sculpted is only partly formed. The neck and head are finished but the body of the sculpture has not yet been carved. The unformed body of Pygmalion’s sculpture can be seen as symbolic of the formless matter of alchemy that invites projection and creation on the part of the artist.

Interpretation of the Pygmalion illumination is further expanded by Jung’s alchemical views of death. Blamires & Holian (2002) point out that the female shape resembles a corpse with a head protruding from a body tightly wrapped in a funeral sheet. In this way, the illumination invokes “the art of the funeral moment” (p.99) in that it resembles images of the dead that were traditionally carved on top of caskets. If Pygmalion is viewed as a reflection of the Lover and the Pygmalion passage as a reinforcement of the Lover’s journey, the death scene, then, may illustrate the symbolic death of the Lover’s old self as he unites with his anima. Jung discusses this figurative death in alchemical terms stating “No new life can arise, say the alchemists, without the death of the old” (Jung, 1995, p. 202).

The insinuation of death invoked by the Pygmalion scene furthermore calls to mind the integration process of the collective unconscious and may represent the desire of Pygmalion, the Lover and Jean de Meun to integrate all aspects of Self and psychic inheritance. Jung (1995) agreed with the alchemical theory that the psyche contains a collective unconscious that is composed of a “conglomeration of ancestral units, called Mendelian units” (p.140). In Jung’s view, Mendelian units are comprised, not only of physical qualities, but also of psychological elements that are collectively inherited from human ancestors and expressed in character traits. According to Jung, in order to be fully whole with one self, an individual must be able to integrate the ancestral spirits that make up their psyche. Conversely, Jung said: “When someone is threatened with dissolution, it is just as if these particles could not be united, as if the ancestral souls would not come together” (p.142). In short, Jung believed that there is an “other aspect of the dead: it is not only the dead body, but the spirits of the dead” (p.142). The conflict among these Mendelian units, or spirits of the dead, is represented earlier in the Roman de la Rose by the psychic elements that compete for control of Lover’s soul. Threatened with self-dissolution, the Lover moves to come to terms with these chaotic psycho-spiritual traits as Jung describes. “…if a primitive wants to become a medicine man, a superior man, he must be able to talk to the dead, must be able to reconcile them…That is necessary for everybody in order to develop mentally and spiritually. He has to collect these spirits and make them into a whole, integrate them…” (p142). Therefore, in the Roman de la Rose, the Lover’s quest for the rose culminates at the Pygmalion scene, where the Lover must relinquish his old Self in order to fully accept the new whole being he has become. He must turn toward death, as illustrated in the illumination, in order to reconcile the contending forces of the collective unconscious that, until this moment, have prevented him from achieving oneness with himself. The symbolic death of the Lover, the inner reconciliation of the Lover’s contending spirits and the revival of the anima at the end of the Roman de la Rose signify the culmination of the Lover’s quest for unity.

Textual Integrity of the Roman de la Rose

The theme of balance and unity that plays a critical role in the Lover’s discovery of his self in the Roman de la Rose is paralleled by the fusion of the contrasting allegorical styles of Guillaume de Lorris and Jean de Meun. Numerous readers and scholars that have analyzed the Roman de la Rose, object to Jean de Meun’s approach to the continuation of Guillaume de Lorris’ poem (Gunn, 1952; Lewis, 1951; Lowes, 1934). In the opinion of some critics, the radical diversity in the styles of the two authors disrupts the internal consistency of the work and creates an inner disharmony. The idealized account of chivalric romance described by de Lorris progresses into a cynical discussion of virtue and vice by de Meun. Indeed, the continuation represents a broad departure from the original work and calls into question the intentions of the second author. Further, de Meun’s ending is wrought with digressions that appear to deviate immensely from the story line. C. S. Lewis (1951), who is one of the most avid critiques of de Meun’s account, attacks what he perceives to be severe internal inconsistencies in the latter half of the Roman de la Rose. While Lewis applauds de Meun’s vivid imagination and creativity in the conception of the value debates, he contends that de Meun lacks the ability to reintegrate these debates into the larger framework of the chivalric love quest that was the theme of de Lorris’ poem. He therefore dismisses de Meun’s ideas as meaningless and convoluted, seeing them as detracting from the general progress of the story: “…While all these solutions are good, the fatal defect is that they have really nothing to do with one another…All Jean’s ideas were in themselves capable of fusion but he could not fuse them” (154 – 155).

While many scholars will agree that de Meun’s continuation possesses perceived inconsistencies, debate surrounds the contention that his divergence from the first half of the poem interferes with the unity and coherence of the integrated text. In defense of de Meun’s work, Alan Gunn (1952) describes his vision of the latter contribution to the poem:

Jean de Meun designed his own work so as at once to enlarge and to alter the significance of his predecessor’s chivalric romance. In doing so, he made it a member of a new and equally organic poetic structure. That is why one can speak of the completed Roman de la Rose as both an original and a unified work… (325).

In addition to Gunn’s interpretation, the application of psychodynamic principles to an analysis of the textual cohesion of the Roman de la Rose demonstrates that the contrast of the artistic vision of the two authors is what engenders the balance and unity of the completed masterpiece. The concurrent dissonance and collusion of the writing corresponds to the internal struggle of the Lover to assimilate the contrasting forces of his spirit. Just as the human self is composed of opposites, the Roman de la Rose itself is divided into idealistic and cynical halves. The Lover’s human tendency to incorporate the good parts of the psyche into his self-concept and to ignore and repress the bad parts, is mirrored by the unwillingness of scholars to validate a more pessimistic and skeptical approach to idealized love. Furthermore, Jean’s alteration of Guillaume’s original Roman de la Rose manuscript models the alchemic transformation process that is at the heart of the Jungian theory of self-discovery. Just as the ‘Axiom of Ostanes’ can be aptly applied to Jean’s retelling of the story of Pygmalion, on a larger scale it applies to the continuation of Guillaume’s story on the whole. Jean encounters Guillaume’s original Roman de la Rose manuscript and appreciates it, (“A nature is delighted by another nature”), writes a continuation of it, which engenders a qualitative transformation that alters the meaning of the original poem (“A nature conquers another nature”) and the two parts of the allegory form a union, creating a new, unique object, containing parts of both original works (“A nature dominates another nature”).

Conclusion

Through dream symbolism expressed in art and allegory, the Roman de la Rose describes the shared human quest to uncover the self and to attain spiritual congruence by the reunion of our internal opposites. These opposites manifest in the allegorical archetypes through which readers may come to know the dynamics of their collective unconscious. In certain ways, we are all similar to the Lover in that we struggle with a certain internal disharmony which stems from our efforts to control and deny our fears and faults while acknowledging only the socially desirable parts of ourselves. The symbols in the Roman de la Rose were projected and are absorbed largely on an unconscious level. However, their mysterious existence, and the tension that they reveal, has been implicitly recognized by scholars who have appreciated the unique qualities of the Roman de la Rose throughout the centuries.

The present analysis of the Roman de la Rose demonstrates how life themes can be understood through psychodynamic analysis of symbols found in allegory, myth and art. The psychodynamic themes uncovered in the Roman de la Rose demonstrate how psychologists can use works of literature and art as vehicles to help clients better understand themselves and their unconscious processes. It is a long-held belief in psychology that insight into the unconscious contributes to therapeutic relief. Similarly, it is widely thought that the resolution of internal conflicts, as illustrated by the journey of the Lover in the Roman de la Rose, promotes good psychological health. To the degree that we as psychologists remain open to the mystical, complex and intangible aspects of the human psyche captured in dreams, art and myth, we will be better able to address the diverse, anecdotal, and subjective aspects of life that contribute to the collective human experience.

Works Cited

Blamires, A. & Holian, G. (2002). The Romance of the rose illuminated: Manuscripts at the National Library of Wales, Aberystwyth. Tempe, Arizona: Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies.

De Lorris, G. & de Meun, J. (1962) The Roman de la Rose. (H. W. Robbins, Trans.) New York : E. P. Dutton & Co., Inc.

DeLorris, G & De Meun, J. (1974) Le Roman de la Rose. (D. Poirion, Ed.) Paris : Garnier-Flammarion.

Gunn, A. M. F. (1952). The mirror of love: a reinterpretation of the “Romance of the Rose”. Lubbock, Texas: Texas Tech Press.

Haule, J. R. (2011). Jung in the 21st Century Volume One : Evolution and Archetype. New York, NY: Routledge.

Huot, S. (1993). The Romance of the Rose and its Medieval readers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Jung, C. G. (1933). Modern man in search of a soul. (W. S. Dell & C. F. Baynes, Trans.). New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company.

Jung, C. G. (2001). On the nature of the psyche. (R.F.C. Hull, Trans.) London: Routledge Classics.

Jung, C. G. (1958). Psyche and symbol. (V. S. de Laszlo, Ed.). Garden City : Doubleday & Company.

Jung, C. G. (1964). Man and his symbols. (M. – L. von Franz, Joseph L. Henderson, Jolande Jacobi & Aniela Jaffé, Eds.). Garden City : Doubleday & Company Inc.

Jung, C. G. (1974). Dreams. (R. F. C. Hull, Trans.). Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Jung, C. G. (1984). Dream analysis. (W. McGuire, Ed.). Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Jung, C. G. (1990a). The basic writings of C. G. Jung. (V. deLazlo, Ed. & R. F. C. Hull, Trans.) Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Jung, C. G. (1990b).The undiscovered self. (R. F. C. Hull, Ed.). Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Jung, C. G. (1995). Jung on alchemy. (N. Schwartz-Salant Ed.). London: Routledge.

Leushuis, R. (2006). Pygmalion's Folly and the Author's Craft in Jean de Meun's Roman de la Rose. Neophilologus, 90(4), 521-533.

Lewis, C. S. (1951). The allegory of love: A study in medieval tradition. London: Oxford University Press.

Lowes, J. L. (1934).Geoffrey Chaucer and the Development of His Genius. Boston, MA.

McCaffrey, P. (1999). Guillaume de Lorris and Jean de Meun: Narcissus and Pygmalion. Romanic Review, 90(4), 435-449.

Nouvet, C. (1994) “An allegorical mirror: the pool of Narcissus in Guillaume de Lorris’ Romance of the Rose”. The Romanic Review 91.4 (1994): 353 - 374.

Schwartz-Salant, N. Introduction: Alchemy, Science and Illumination. Jung on Alchemy. By C. G. Jung. 1995. London: Routledge.

Stevens, A. (1995). Jungian psychology, the body and the future. Journal of Analytical Psychology, 40, 353 – 364.

Appendix

Figure A1. The Lover Encounters Oiseuse. In this illumination, the Lover discovers a reflection of his Anima in the mirror that Oiseuse holds. He is drawn into his Personal Unconscious by way of the mirror.

By permission of Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru/ The National Library of Wales

.

Figure A2. Narcissus Gazes at the Spring. In this illumination, the Lover discovers deeper layers of his Self through his reflection in the Pool of Narcissus. The mirror of the water serves to draw the Lover into his Collective Unconscious.

By permission of Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru/ The National Library of Wales

Figure A3. Pygmalion Sculpts a Female Form. In this illumination, the Lover, represented by Pygmalion, reunites his Anima and Animus. Pygmalion projects his Anima onto a statue he carves, falls in love with it, and prays that it be brought to life.

By permission of Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru/ The National Library of Wales

[1] Illuminated miniatures were commonly used during the Middle Ages as supplements to written works. They were artistic images often carved out of wood and stamped onto the pages of manuscripts. They range from simple and iconographic to ornate and extravagant and were used as accompaniments to written text, often functioning to underscore the meaning of a story.

[2] The Aberystwyth collection contains five manuscripts that are illuminated. It was originally made by Francis Bourdillon, a British poet, translator and renowned Roman de la Rose scholar.

Received: October 31, 2011, Published: May 1, 2012. Copyright © 2012 Amy Kincaid Todey