Arabic Poet Al-Mutanabbi: A Maslovian Humanistic Approach

by

Ratna Roshida Abd Razak

December 14, 2007

This paper is concerned with the Maslovian “real self” of al-Mutanabbi, a great poet of the Abbasid period (750-1258 AD). I have made an effort to discover the deeper aspects of al-Mutanabbi’s personality, which constitute an important aspect of his artistic expression. The study I’ve undertaken here -- a humanistic psychological approach to Arabic poetry -- will deal with some general ideas about humanistic psychology and al-Mutanabbi’s poetry. I will employ Maslovian theory to consider al-Mutanabbi as a self-actualizing person. This attempt is made to see how humanistic psychology can open the door to a new world in the study of Arabic poetry and help us to understand the greatness and insight of the works of al-Mutanabbi. In spite of his great poetic achievement, particularly during the Abbasid period, Maslovian theory reveals the poet to us as a complex and fascinating human being.

Introduction

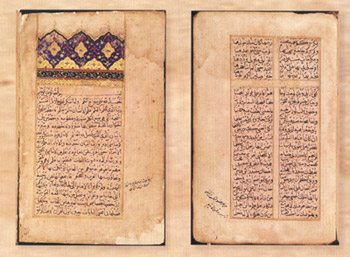

Abu al-Tayyib Ahamad Ibn al-husayn Ibn al-Hassan Ibn Murra Ibn Abd al-Jabbar known as al-Mutanabbi, a poet of the Abbasid era (750-1258 AD), occupies a place of supremacy in the annals of Arabic poetry. Readers of Arabic culture acknowledge that his Diwan (collection of poems)1 along with the Quran and the Maqamat (writings) of al-Hariri constitute the pinnacle of Arabic writing, all three venerated in the same way that English readers treasure the King James version of the Bible and the works of Shakespeare. Most of his poems could be classified as poems of praise and satire and most were composed for and dedicated to his patrons. Al-Mutanabbi’s work is still read and appreciated to this day in the Arabic speaking world. His poetry is considered unique in the history of classical Arabic literature and serves as the vehicle for his immortality.

Even though al-Mutanabbi has been the subject of a considerable number of studies from a variety of perspectives, in both the East and the West, not much attention has been paid to the humanistic aspect or to the psychology of the man himself, with the exception of a 1995 article by J.E. Montgomery entitled “Al-Mutanabbi and the Psychology of Grief.” No great effort has been made to dig beneath the surface in order to examine his strong and forceful personality. Many modern studies of Arabic poetry have focused on al-Mutanabbi’s verses, concentrating on the construction of the poems and the instruments employed by the poet to compose his polythematic poetry, while ignoring the man’s psychological makeup (Van Gelder 5).

Arabic literature, in particular poetry, and especially during the Abbasid period, is a vast repository waiting for psychological insight. Jung comments that the most fruitful subject for the psychologist is the poet who has not yet committed to paper a psychological interpretation of his own character. The poet leaves ample room for the psychologist to analyze, examine, and interpret his poetry. According to Jung,

An exciting narrative that is apparently quite devoid of psychological exposition is just what interests the psychologist most of all. Such a tale is built upon a groundwork of implicit psychological assumptions, and, in the measure that the author is unconscious of them; they reveal themselves, pure and unalloyed, to the critical discernment. (Modern 178)

I have undertaken this psychological study of al-Mutanabbi in order to continue the efforts that have been made to examine the nature of artistic creativity, which is still one of the most ambiguous and incomprehensible issues in the realm of psychology. The various aspects of poetic creativity in general may also be applied to other art forms, for the arts have many features in common, emerging from one source, namely the human psyche. Jung acknowledges the intangible character of artistic creation:

Creativeness, like the freedom of the will, contains a secret. The psychologist can describe both these manifestations as processes, but he can find no solution of the philosophical problem they offer. Creative man is a riddle that we may try to answer in various ways, but always in vain, a truth that has not prevented modern psychology from turning now and again to the question of the artist and his art. (Modern 192-93)

Humanistic Psychology and the Artist

To investigate the personality of a poet, there is one promising psychological theory, known as humanistic psychology, that may provide new insights. There are three important proponents of this theory, namely Carl Rogers, Abraham Maslow and Karen Horney. This theory offers a comprehensive account of psychological growth; it concerns a way of life, not only of the person as a separate individual, but also of the person as a social being, an integral member of society.

Humanism is here taken to be a theoretical orientation that emphasizes the unique qualities of humans, especially their free will and their potential for personal growth. Humanistic psychology originated in the United States of America. The American capitalist ideology puts stress on the individual striving to become what she can. The innate striving toward self-fulfillment, along with the realization of a person’s own unique potential is the constructive, guiding force that motivates each person to become engaged in generally positive behaviors and to enhance the self (Zimbardo 437). A person who recognizes herself as being in possession of artistic talent may have a need to pursue art for its own satisfaction. As a component of self-satisfaction, art may be pursued instead of monetary ends. Without art, a gap is left in the artist’s life. Humanistic theory also proposes that the environment has a very important role to play, having an enormous impact on the growth of the individual. The individual will fulfill her genetic potential, become strong and self-directing if the environment seems favorable for growth and is based on real needs. When growth is naturally encouraged, then honesty and openness will prevail.

Maslovian Theory

Abraham Maslow, was a humanistic theorist who believed that an accurate and viable theory of personality must include not only the depths, but also the heights that each individual is capable of attaining. His theory mainly relies on mentally healthy human beings, and is based on the concept that human beings are governed by a hierarchy of biologically based needs. He used the word “hierarchy” because he felt that these needs formed a hierarchy of propensity, since the lower needs must be satisfied in order to be able to move on and gratify the upper ones (Toward 27).

According to Maslow, the most basic human needs are physiological, the needs for oxygen, food, and water; next, when physiological needs have been satisfied and are no longer occupying a person’s thoughts and actions, come the needs for safety and security; then the needs for love, affection and belonging follow. And when these first three categories of needs are satisfied, the needs for esteem, both esteem from others and self-esteem, become salient. Self-actualization, according to Maslow, is the last step of the hierarchy, at the top of the pyramid; it is a person’s need to be and do what the person was “born to do.” So, the hierarchy of needs goes in this order, starting from the most basic: physiological; safety and security; love, affection and belonging; esteem and, finally, self-actualization.

Maslow’s theory is primarily concerned with that part of human motivation and behavior which is based on the higher needs. He concentrates on the process of self-actualization in the movement that a healthy person makes toward “the actualization of his potential, capacities and talents.” Maslow’s prime concerns are the highest needs which incorporate motives for growth. He defines self-actualization as the “full use and exploitation of talents, capacities, potentialities as fulfillment of mission” (Toward 35). In addition to this, it is an episode, or a spurt, in which the powers of the person come together in a particularly efficient and intense, as well as enjoyable, way. Maslow also argues that self-actualization is not a static condition, but an ongoing process of using one’s capacities fully, creatively and joyfully. Maslow finds that self-actualizing people are dedicated to a vocation or a cause.

Actualizing the real self demands a culture that offers a course of activity congruent with the individual’s inner bent, and which permits the individual to realize her capabilities. In childhood there also needs to be a set of significant adults who are interested in the child as a being in herself, and who will also allow the child to have her own feelings, tastes, interests and values (Toward 58). Wherever possible, the child must be allowed to exercise her own choices. The child’s own understanding of her inner nature and acting in accordance with it is essential, especially because self-actualizing people, those who have come to a high level of maturation, health and self-fulfillment, have so much to teach us that sometimes they seem almost like a different breed of human being (Toward 71).

In Maslovian terms, the child is a weak and dependent being whose needs for safety, protection and acceptance are so strong that he will sacrifice himself, if necessary, in order to get these things. If the child is faced with a choice between his own delightful experience and the approval of others, he generally will choose approval. Generally speaking, this will lead to the development of disapproval of the delightful experience, embarrassment and secretiveness about it, and finally the inability even to experience it. The self-actualizing person, however, will be occupied, not with controlling the urges of his ego, or with becoming “well-adjusted” to his society, but with cultivating the development of the real self, his human nature. He will expose to himself the real self and this exposure will be manifested in his greater congruence, his greater transparency and his greater spontaneity.

Personality is displayed in many ways, for example through behavior patterns, thoughts and feelings. Behavior is the result of drives and, furthermore, associations develop between drive stimulations and objects or responses (Deci 6). Humanistic theory postulates that the motivation for behavior comes from a person’s unique biological and learned tendencies, and capacity to develop and change positively in relation to the goal of self-actualization, which is the desire to realize one’s potential (Toward 113).

The Application of Maslovian Theory to Al-Mutanabbi and His Poetry

Al-Mutanabbi was born in 303 AH/915 CE and thus witnessed at first hand the chaotic situation Islam found itself in: the Sunni caliphate was being beleaguered by an increasing number of Shi’ite dynasties, like Ikhshidid in Iran, the Hamdanid in Aleppo and the Buwayhids in Iran and Iraq. The Shi’ite environment in which al-Mutanabbi had grown up, and his experience of the Carmathians in both Kufah and Syria, all of which he regarded as instruments of spiritual oppression, led him to become very stoical. Because of this, as the Egyptian scholar, Muhammad Muhammad Husayn, points out in a booklet entitled al-Mutanabbi wa al-Qaramitah, al-Mutanabbi became a fanatical anti-Carmathian.

Al-Mutanabbi’s father, al-Husayn Ibn al-Hassan Ibn Murra Ibn Abd al-Jabbar, a descendant of an ancient Yemeni clan known as the Banu Ju’ff, is said to have been a water carrier, a rather lowly occupation (al-Baghdadi, 103). It is also said that his father was known as Abdan (al-Wahhab Azzam 28). In the Muslim World, Yemenis were renowned as stalwart soldiers, generous hosts, and lovers of both poetry and eloquence. They were also held to be quarrelsome, strongly conservative and individualistic. Al-Mutanabbi himself was convinced of the superiority of the Arabs of the South over those of the North, largely because of his association with them. He had devoted his life to asserting and fulfilling his ideology. The pattern of his ideal life as an individual and of the community was based on the Arab ideology of chivalry and the high ideal of sincerity.

No reference to either al-Mutanabbi’s father or his mother appears in his Diwan. According to Abdul al-Wahhab Azzam, this is probably because, during his boyhood, he was accused of committing a serious offence against the whole community while still below the age of legal responsibility. In order to conceal his identity, he disowned his grandfather’s genealogy as well as his own (91). It could be argued that another reason for the concealment of his genealogy is that he did not want other people know that he belonged to the lower strata of society. This is because for him honor could be attained through his own self, not in his ancestors. As he asserted,

Not in my people have I found honor but rather they in me

And my boast is in myself, not in my ancestor. ( Arberry, Poems 22)

The only member of al-Mutanabbi’s family mentioned in his poetry is his maternal grandmother, a woman of a tribe called Hamdan, which originated in southern Arabia. His life of long traveling had kept him from his beloved grandmother. In an elegy to his grandmother, al-Mutanabbi, on his way to Baghdad, revealed that he had written her to announce his return after a long absence, and she had died upon receiving this joyful news:

Oh how you are bereaved of your beloved

Victim of a passion that carries no disgrace.

I forbid my heart happiness, for her death

I consider that from which she dies poison. (Larkin 18-37)

The political and cultural environment in the 4th AH/10th CE century had a great impact on the growth of al-Mutanabbi, for it helped to develop his powerful assertion of individualism, as witnessed by a burst of personal expression in the domain of literary creativity as well as political action. Al-Mutanabbi fulfilled his genetic potential and became strong and self-directing when the environment was favorable for him to grow, especially when he had the chance to be under a famous and great patron like Sayf al-Dawlah. When this growth in natural channels was encouraged, then his honesty, sincerity and openness prevailed.

In this essay I will employ Maslovian theory to examine Al-Mutanabbi’s life with Sayf al-Dawlah. This is because in Maslow’s theory, the two concepts, “love” and “creativity” play a vital role in the self-actualization process. Likewise in al-Mutanabbi’s case, we can make a plausible assumption that these two attributes are crucial elements in his relationship with Sayf al-Dawlah.

The Search for Safety

In spite of its political turmoil especially when the Carmathians, a revolutionary group, who called for radical changes in economic, social, political and religious life, the 4thAH/ 10thCE century witnessed a remarkable growth of cultural life. Cultural and intellectual activities developed in an environment of material prosperity and religious heterodoxy. The age’s creative achievements had a personal and individual character. This period also witnessed the emergence of an affluent and influential middle class, which was keen to acquire knowledge and social status. The pursuit of knowledge was considered to be a path toward human perfection and happiness.

In al-Mutanabbi’s time, rank and status were determined by knowledge, intelligence and talent. Rulers and statesmen were avid patrons of learning, entertaining philosophers, scientists and men of letters in resplendent courts where the cultural elite included poets, scholars and scribes. The provincial courts of local rulers and viziers also became the center of intellectual activity. Poets served in all these courts as panegyrists, while scholars acted as scribes, historians, astronomers, advisors, spies and purveyors of edification and delight.

From the early Abbasid era, patrons were often among the well-versed in Arabic literature and poetry. Many of them had received a thorough training from philologists who played a very important role in Arabic life. For religion and political purposes, many Abbasid caliphs were keen to be defenders of the faith. To do so, they needed to master Arabic. In the courts and homes of the patrons, men of letters gathered. For the patrons, the way to earn prestige was by demonstrating their discernment and devotion to Arabic literature and Islamic culture through largesse. For the men of letters, support meant livelihood and sometimes fortune. In order to please patrons, poets had to compose panegyrics (love poems) that satisfied their patrons by showing mastery of the language. The poet would be conferred prestige after giving praise for his patron’s accomplishments and composing scathing satires of his enemies. Thus, the poets wandered from court to court in search of a good patron.

According to Arabic scholar A.J. Arberry, from the outset, the Arab poet was understood to perform a clearly defined social function, namely to sing the praises of his tribe, to defend its honor and attack its enemies, as well as to rouse his people to military zeal through stirring poetry (Arabic Poetry 2). The recital of a panegyric was an important formal occasion and provided an opportunity for the sovereign to demonstrate his generosity publicly by handsomely rewarding the poet, who, if he genuinely, but secretly admired his patron, could be inspired to produce truly excellent work.

Using this as a starting point, in order to psychologically analyze al-Mutanabbi based on his poetry composed to his patron Sayf al-Dawlah, I will focus primarily on al-Mutanabbi as a poet rather than an individual.

According to humanistic psychology, safety needs include physical well-being as well as psychological security derived from stability, predictability, and structure. Al-Mutanabbi needed a strong, protective patron who not only valued his poetry, but also was able to give him many opportunities to display his talent as a poet. Only such knowledgeable, generous patronage would allow him to achieve fame and a comfortable livelihood as a poet. In 337AH/948CE al-Mutanabbi finally succeeded in attracting the attention of the illustrious Hamdanid ruler of Aleppo, Prince Sayf al-Dawlah. The Banu Hamdan was a distinguished Arab family of Bedouin origin and Shi’ite inclination. They played a vital role as warriors in affairs of the declining Abbasid caliphate from near the end of the 3rd/9th century until about the end of the following century.

Al-Mutanabbi was able to feel safe and secure in the company of Sayf al-Dawlah, who became his intimate friend and comrade in arms. As a result, al-Mutanabbi was better able to appraise the heroism of the prince wholeheartedly. Furthermore, from his patron’s constructive energy he gained strength that urged him on towards inner freedom. It also gave him the power to sustain the inevitable pain of maturation and made him willing to take the risk of changing attitudes that had given him a feeling of safety. He started to feel the need to fulfill other desires, an indication of his healthy growth.

The Need to Belong and Affection

When physical needs are largely satisfied and a sense of safety and security is in place, the needs for love, affection and belonging come to the forefront as motivations. We could consider that al-Mutanabbi now hungers for affectionate relationships with friends, and specifically with a powerful and influential patron. Having gained intimate knowledge of Sayf al-Dawlah, we can presume al-Mutanabbi then grew to love him as his patron. It could be considered that he was expressing his love to Sayf al-Dawlah when he said that he had chained himself to Sayf al-Dawlah:

I chained myself to your love in affection

He who loves good deeds is held by a chain. (Wormhoudt 373)

From the verses that were written in his happy period at the court of Sayf al-Dawlah, we could consider that al-Mutanabbi was able to enjoy feelings of belonging and affection:

Every day you load up fresh

and journey to glory, there to dwell

And our wont is comely patience

were it with anything but your absence that we were tried

Every life you don’t grace is death

every sun that you are not is darkness. (Arberry, Poems 5)

The Need for Self Esteem

Assuming that at this point the first three levels of the hierarchy of al-Mutanabbi’s needs were adequately satisfied, we would expect him to be concerned with the needs for esteem. Maslow distinguishes two types of esteem needs. The first is esteem from others. This involves the desire for reputation, status, recognition, fame and a feeling of being useful and necessary. Individuals need to feel respected and valued by others for their accomplishments and contribution. Self-esteem, on the other hand, involves a personal desire for feelings of competence, mastery, confidence and capability.

Self-esteem is therefore closely linked to the desire for superiority and respect from others, and to some extent, these are part of an accepted practice in Arabic poetry. Moreover, for the Arabs, poetry is a source of pride and rivalry. So the poet, by skilful ordering and vivid imagery could play upon the emotions of his listeners. Al-Mutanabbi’s pride, for example, can be seen in the following verses:

In whom indeed is the pride of every true Arab

and the refuge of the wrongdoer , and the succor of the outcast.

If I am conceited, it is the conceit of an amazing man who has

never found any surpassing himself. (Arberry, Poems 22-23)

The fulfillment of the need for self-esteem is an indication of healthy growth since it will release feelings of self-confidence, worth, strength, capability, and adequacy, of being useful and necessary in the world.

Prompted by the envy and jealousy of the rivals when he was at Sayf al-Dawlah’s court, al-Mutanabbi’s customary arrogance, his intemperate and unbridled boasting appears in his own poetry. For example, he says,

Reward me, whenever a poem is recited to you, for it is only

with my poetry repeated that panegyrists come to you.

And disregard every voice but mine, for

I am the singer who is mimicked; the rest are the echo. (Khalaili 8)2

The Quest for Self-Actualization

Al-Mutanabbi began to attain the final level of Maslow’s hierarchy after he had satisfied his physiological needs and those for safety, love, belonging and self-esteem. This final level of Maslow’s hierarchy is known as that of “self-actualization”—in other words, becoming what one is uniquely adapted to be by nature and temperament.

Al-Mutanabbi’s aim in life could never be realized unless he was utterly true to his own self and nature. As a self-actualized person, he could be defined as someone who was no longer principally motivated by the needs for safety, belonging, love, status and self-esteem because these needs had already been satisfied. However, we may wonder what motivated him, or in other words, what were the psychological systems and theories that gave him motivation and drove his central concepts.

The components of the real self are potentialities. Al-Mutanabbi, who was given the appropriate conditions, i.e. working under a great patron, was able to grow to realize his inherent potential. He became more completely himself. Thus, he became more easily self-expressive and spontaneous without effort, more daring and courageous. He launched himself fully into the stream of life. He had attained a healthy sense of the self as he was provided with a proper emotional climate, since humans will only grow to be emotionally healthy if they are surrounded by warmth and acceptance.

A Self-Actualizer’s Love

Love, for a self-actualizer, consists primarily of a feeling of tenderness and affection coupled with great enjoyment, happiness, satisfaction, elation and even ecstasy. In the most desirable way, the self-actualizer’s beloved is perceived as beautiful, good and attractive. There is a simple pleasure in looking at, and being with, the loved one. As a result, there is a tendency to focus complete attention on the loved one, to forget other people, to narrow perception in such a way that other things are not noticed.

From the love poem composed during his period with Sayf al-Dawlah, we can conclude that Al-Mutanabbi’s love for Sayf al-Dawlah grew out of his more than satisfactory life with his patron. As the self-actualizer’s love relationship continues, there is a growing intimacy and honesty and self-expression, which when at its height is a very rare phenomenon. Al-Mutanabbi’s intense love for his patron can be deduced from the verses below:

Why do I hide this love which wastes me away

While for Sayf al-Dawlah the world feigns love?

Since we all must love him, let us share his love

Proportionally according to our love of him. (Jayyusi and Middleton 87)

Al-Mutanabbi’s expression of his undying love for Sayf al-Dawlah appeared when he mentioned the latter’s bravery in his wars with the Byzantines. It shows that he genuinely admired, as well as loved, the Hamdanid prince. He also celebrates the prince’s exploits in war, by using martial images that strongly assert valor and an enduring will to cut down the enemy (Jayyusi 9).

I’ve visited him when the Indian swords were sheathed

And I’ve seen him when swords were dripping blood.

The flight of your enemies is victory enough

Encompassing at once triumph and regret.

The rumors of your valor made them flee in fright

The terror of your name inspired more fear than a mighty army. (Jayussi 9)

In composing this panegyric, al-Mutanabbi expressed his gratitude as an all-embracing love for Sayf al-Dawlah. His impulse to praise his patron far transcended the responsibilities of his position.

There I remembered a union it was as if I had never attained

and a pleasurable period it was as if I had passed in one leap.

And a maiden of bewitching eyes, mortal and desire

When her sweet perfume diffused over an old man he became youthful again.

And O my yearning, how long you have continued!

And O, who will deliver me from the anguish of separation. (Arberry, Poems 64)

Al-Mutanabbi’s strong love for Sayf al-Dalwah who can be regarded as his beloved in a spiritual sense, manifested itself perhaps most acutely when he was separated from him. He fondly remembered his beloved at this time and resigned himself to his fate:

I desire of the Days that which they do not desire, and I

complaint of our separation to them, but they are its warriors.

They banish far a love with whom we are co-joined. So how much

more the case with a love from whom we are divided

The temper of this world [is such that it] will not let a loved

One stay for long, so how can I ask it to bring back a loved

One [that has gone]. (Khalaili, Poem 4: 1-3)

In the eyes of al-Mutanabbi, Sayf al-Dawlah was a perfect figure, a role model embodying all that he admired. He personified the Bedouin style of life in Syria with which al-Mutanabbi was so fascinated. Sayf al-Dawlah also possessed the valorous spirit of the desert: he led his warriors into battle personally and never hesitated to engage in hand-to-hand combat.

Creativity and the Self-Actualizing Person

According to Maslow, the most universal characteristic of all the people he studied and observed was their creativity. Regarding this, he notes that a fundamental characteristic of human nature is the potential to be creative which is given to all human beings at birth. (Maslow opines that genius, talent and productivity are not synonymous since some of the greatest talents, men like Van Gogh and Byron were not psychologically healthy people. For him, creativity is the universal heritage of every human being and it co-varies with psychological health).

Every self-actualizing person displays a fresh and creative approach to life, a virtue by no means limited to the artist or genius. Literary critic al-Tha’alabi lists among the creative innovations which al-Mutanabbi introduced “addressing the patron as one addresses one’s beloved,” and “using expressions proper to love poetry in the description of war” (34).

The majority, both of Eastern and Western critics, agree that al-Mutanabbi’s poetic performance during his life with Sayf al-Dalwah marked the zenith of his profession. It is important to note that, during this period, he accomplished commendable levels of poetic production and maturity. The poet’s ability to invent something, which would leave its mark on the listener’s soul and inspire emotion and passion determined the estimation of his talent. It was judged according to how far it could raise listeners’ appreciation to the level of intense delight. It can be argued convincingly that al-Mutanabbi was at his most brilliant in his Saifiyyat-collection of poems, produced during his time with Sayf al-Dawlah.

Conclusion

To recapitulate the discussion, I show that four basic tendencies characterized al-Mutanabbi’s journey toward his self-actualization. The first tendency was to strive for his personal satisfaction in ego recognition. The second was to struggle toward self-limiting adaptation for the purpose of belonging and gaining security. The third was toward self-expression and creative accomplishments and the last was toward integration or order upholding.

Al-Mutanabbi’s creativity flowed spontaneously from his personality and the key to al-Mutanabbi’s triumphs as a panegyrist lies in his relationship with Sayf al-Dawlah. We might also affirm that al-Mutanabbi was consciously and courageously struggling towards authentic self-development. However, it is especially difficult to judge how far al-Mutanabbi actualized himself as a poet. As we are dealing with internal matters, it is impossible to prove absolutely any hypothesis concerning a figure from the past. Maslovian theory may nevertheless be of considerable value in allowing us to understand the motivation and the mental and emotional structure of the creative individual in general.

Al-Mutanabbi’s safety need predominated until he obtained secure patronage from the Hamdanid prince, Sayf al-Dawlah, an aristocratic warrior and the personification of Arab chivalry whose court was renowned as a center of intellectual and cultural excellence. We could say that the fundamental goal which motivated al-Mutanabbi during his time with Sayf al-Dawlah was to become a great poet. His desire to secure a special place at Sayf al-Dawlah’s court reflected his ambition to achieve mastery over his art, and his privileged position was to be the means of attaining it. Apart from that, it provided an indication of the poet’s power of creativity, his emotional, intellectual as well as imaginative talents.

It is crucially important to note that for humanistic psychology in general and Maslovian theory in particular, the problem of creativity is the problem of the creative person (rather than of simply the creative product, or of creative behavior). In other words, the ‘creative person’ is not a special kind of person, but one in whom creativity is developed to an unusually strong degree. Since creative people embody the essence of all of our creativity, they represent the problem of the transformation of human nature, the transformation of character, and the full development of the whole person in Maslovian terms.

I hope that this essay, applying Maslovian theory to al-Mutanabbi as a poet, will contribute to our appreciation of the brilliance and genius of one of the truly great masters of Arabic literature.

Notes

1 This essay contains quotes of al-Mutanabbi’s poems which are found in several works by several translators; therefore I felt it was clearer to cite the translator and the page number after each quote, rather than the work in which the translation is found and the page number. The translators as listed by last name in the Works Cited.

2 I believe that al-Mutanabbi’s pride at this time is a healthy one. It is based on the substantial attributes and a warranted high regard for hi special achievement.

Works Cited

Adonis. An Introduction to Arabic Poetics. Trans. Catherine Cobham. London: Saqi Books, 1999.

Ahmad, M. M, A Critical Edition of Kitab al-Fasr, Ibn Ginni’s Commentary on the Diwan of al-Mutanabbi. University of St. Andrews, 1984.

Arberry, A. J. Arabic Poetry, A Primer for Students. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1965.

_____. Poems of al-Mutanabbi, A Selection with Introduction, Translation and Notes. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1965.

Aronoff, Joel. Psychological Needs and Cultural Systems. Princenton: Van Nostrand, 1967.

Azzam, Abd al-Wahhab. Dhikra Abu al-Tayyib Ba’da Alf Am. Cairo: n.p., 1994.

Al-Baghdadi, Al-Khatib. Tarikh Baghdad. 14 vols. Cairo: n.p., 1349-55.

Al-Barquqi, Abd al-Rahman, Sharh Diwan al-Mutanabbi. 2 vols. Cairo:n.p., 1930.

Charlton, H. B. The Art of Literary Study. London: n.p., 1924.

Deci, Edward L. Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior. New York: Plenum, 1985.

Dew, R. P. “The Poetry of al-Mutanabbi.” Journal of Royal Asiatic Studies (1915): 118-122.

Feibleman, James K. “The Psychology of the Artist.” Journal of Psychology 9 (1945): 165-189.

Fromm, Erich, ed. The Nature of Man. New York: Macmillan, 1968.

Husayn, Taha. Ma’al al-Mutanabbi. Cairo: Dae al-Ma’arif, 1949.

Jayyusi, S. K. “The Persistence of the Qasida Form in Qasida Poetry in Islamic Asia and Africa.” Qasida Poetry in Islamic Asia and Africa. 2 vols. S. Sperl and Christopher Shakle, eds. Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1996.

Jayyusi, S. K. and C. Middleton, Trans. “Qasida 5: 2-3.” Qasida Poetry in Islamic Asia and Africa. S. Sperl and Christopher Shakle, eds. Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1996.

Jung, C. G. Modern Man In Search of a Soul. London: Ark Paperbacks, 1992.

_____. Man and His Symbols. New York: Doubleday, 1964.

Khalaili, K. Al-Mutanabbi in his Role as Eulogist and Satirist of Kafur: A Study Edited Text and Annotated English Translation of the Kafuriyyat. Manchester: U of Manchester, 1978.

Larkin, M. “Two Examples of Ritha: A Comparison between Ahamad Shawqi and al Mutanabbi, Journal of Arabic Literature 14 (1990): 18-37

Maslow, A. H., “Higher and Lower Needs.” Journal of Psychology 25 (1948): 433-346.

_____. “Deficiency Motivation & Growth Motivation.” Nebraska Symposium on Motivation: 1955. ed. M. R. Jones. Lincoln: U of Nebraska P, 1955.

_____. ed. New Knowledge in Human Values. New York: Harper, 1959.

_____. “Self-Actualizing People.” Reprinted in The World of Psychology. G.B. Levitas, ed. New York: Braziller, 1963.

_____. Motivation and Personality. New York: Harper, 1954.

_____. The Farther Reaches of Human Nature. New York: Viking, 1971.

_____. Toward a Psychology of Being. New York: Van Nostrand, 1968.

_____. The Healthy Personality: Readings. New York: Van Nostrand, 1969.

Montgomery, J. E. “Al-Mutanabbi and the Psychology Grief.” Journal of the American Oriental Society 115.2 (1995): 285-292.

Sperl, Stefan, “Islamic Kingship and Arabic Panegyrics Poetry in the Early 9th Century.” Journal of Arabic Literature 8 (1977): 20-35.

Al-Tha’alibi, Abu Mansur Abd al-Malik Muhammad Ibn Ismail al-Naysaburi Abu Tayyib al- Mutanabbi, Wa malahu Wa ma’alaihi. Cairo: n.p., 1915.

Van Gelder, Jan Geert. “Al-Mutanabbi’s Encumbering Trifles.” Arabic and Middle Eastern Literatures 2.1 (1999): 5-19.

Wormhoudt, A., Trans. and ed. The Diwan of Abu Tayyib Ahmad ibn al-Husain al-Mutanabbi, al- Saifiyyat. 2 vols. Oskaloosa, Iowa: William Penn College, 1971.

Zimbardo, Philip G. Psychology and Life, 12th ed. London: Scott, Foresman, 1988.

Received: January 1, 2007, Published: December 14, 2007. Copyright © 2007 Ratna Roshida Abd Razak