Snarling into the Abyss: An analytical account of the psychological meaning of distortion in Francis Bacon’s (1909 – 1992) portraiture

by

Stephen Quigley ,

Mark A. Elliot

,

Mark A. Elliot

February 20, 2014

In addressing this topic, the article will firstly give an introduction to the life and work of Francis Bacon, this is followed by a discussion of the meaning of distortion in a general sense, and then with specific reference to Bacon’s art. Prior to analyzing Bacon’s motivation to distort it is necessary to outline the effect which distortion has on observers of his art. Both Bacon’s conscious and subconscious motivations to distort are then theorized and discussed.

Snarling into the abyss:

the psychological meaning of distortion in Francis Bacon’s portraiture.

Stephen Quigley and Mark Elliot

In addressing this topic, the article will firstly give an introduction to the life and work of Francis Bacon. This is followed by a discussion of the meaning of distortion in a general sense, and then with specific reference to Bacon’s art. Prior to analyzing Bacon’s motivation to distort it is necessary to outline the effect which distortion has on observers of his art. Both Bacon’s conscious and unconscious motivations to distort are then theorized and discussed.

It is taken for granted that the reader has at least a cursory knowledge of the life and works of Francis Bacon. It is nevertheless necessary to outline some important life events to give context to our topic. Bacon was born in Dublin in 1909, the only child of Eddy Bacon, a retired British army officer, and Winnie Bacon, a steel business heiress. Bacon had a troubled childhood, overshadowed by World War 1, chronic sickness and homosexual tendencies. Bacon was banished from the family home of Straffon lodge in 1926, when his father found him admiring himself in front of a large mirror wearing his mothers underwear. Prior to earning a living from his art, he spent most of his time living in London on allowances from his mother. Nevertheless, Bacon still managed to

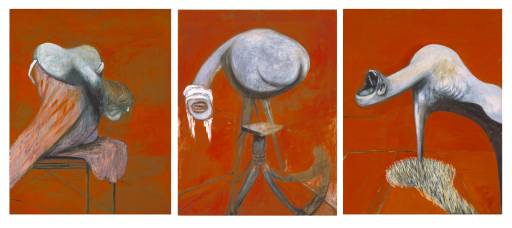

Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion (1944). Tate Gallery, London

live in occasional comfort through the generosity of rich gentlemen who’s company he would frequent. It was not until the mid 1940’s that his career as an artist began to truly flourish. His works ‘three studies for figures at the base of a crucifixion’ (1944) and ‘Painting’ (1946) are among his greatest. When Painting sold for £200 in 1946 Bacon promptly moved to Monte Carlo where he remained for 2 years. By 1949 he couldn’t even afford to buy a canvas (“Francis Bacon (painter)”, 2008). He himself described his life as being lived “between the gutter and the Ritz” (Cronin, 2000). Fond of excess, a terrible money manager, Bacon was nevertheless notoriously generous with friends. Bacon undoubtedly knew great suffering, but also great luxury. He had a number of relationships throughout his life, in the end bequeathing his entire estate to a close friend John Edwards. On occasion, Bacon had to rely on his wit alone for survival. Although he had little formal schooling Bacon had an astute understanding of people; both their strengths and weaknesses.

Painting (1946) Museum of Modern Art

Bacon’s art is focused on humanity, the human condition. His paintings nearly exclusively depict humans or humanoid beings. His portraiture depict humans on a similar scale; approximately three-quarters life size, they tend to be solitary and are frequently contorted in some manner, be it physical or emotional. The distortion of the face is a common feature in much of his art; specifically the area above the mouth was frequently obscured or omitted in some way. This distortion is all the more apparent due to the level of detail often afforded to other features such as the mouth itself. This distortion was clearly deliberate. It is not from lack of artistic ability that features were distorted, rather it was a calculated decision. Since the distortion of the face is so prevalent, it is this specific area of distortion that the article focuses on. However, firstly we must ask what exactly it means to ‘distort’.

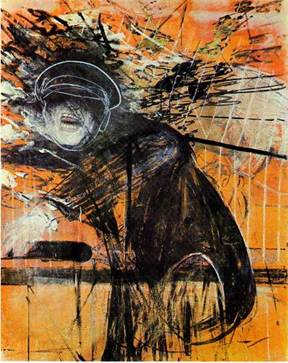

Man in a Cap (c.1943)

Distort: “to twist or pull out of shape” (Davidson, 2006)

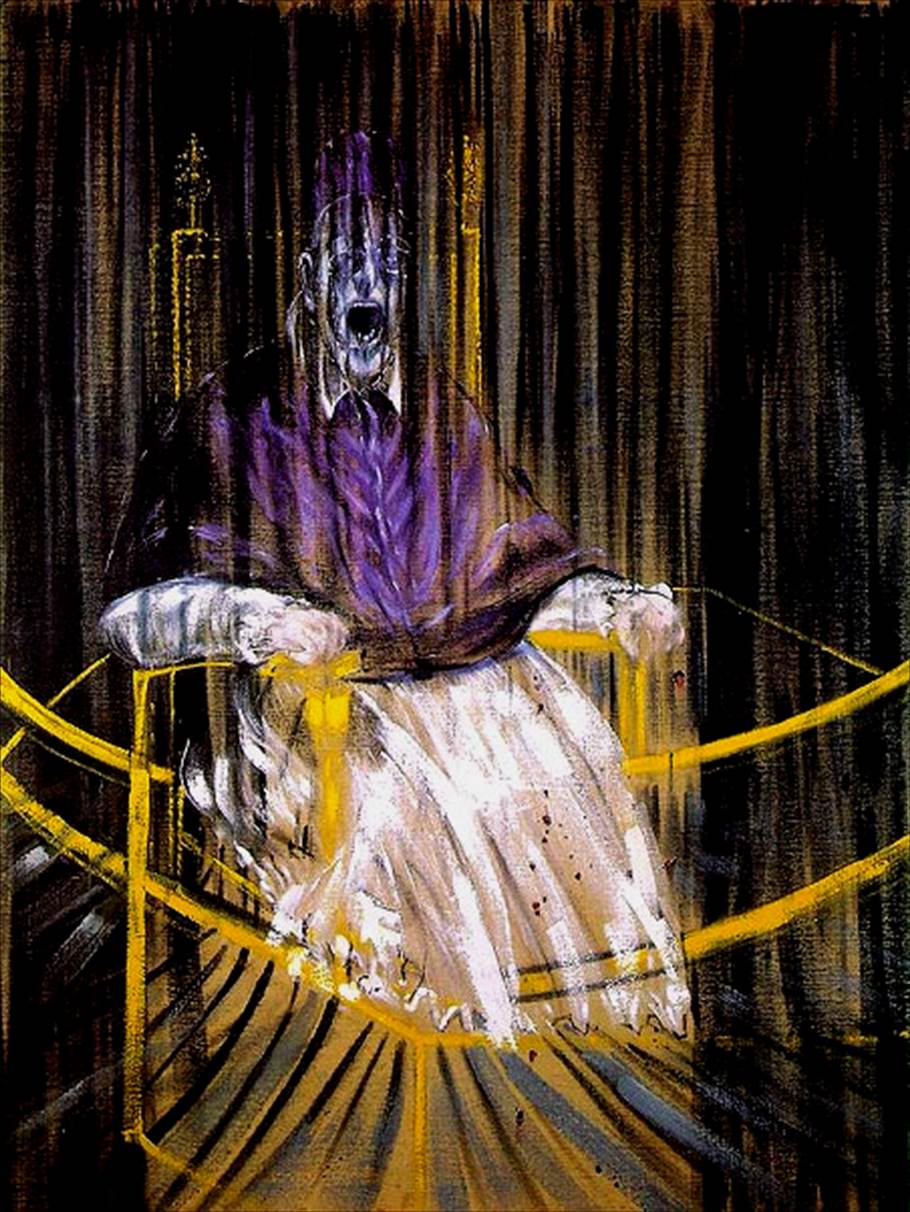

In order for distortion to occur, there must be some norm that is altered. Since the norms that bind society change considerably across cultures and time, so too must the ‘distortion’ of these norms. In order to label something as distorted within the world of art we must first enquire as to what the artist intended to represent. To illustrate this idea I will refer to ‘Study after Velazquez’s portrait of Innocent X’. If Bacon had intended to create an accurate physical representation of Pope Innocent X then we should conclude that he failed miserably. However, if instead Bacon intended to represent a nightmarish image which seethes with aggression, and yet communicates the inherent isolation of the pontiff’s position, than his work is perfectly accurate. It therefore must be recognized that distortion does not equate to misrepresentation. Bacon’s art itself is not distorted, our understanding of visual reality is challenged, and it is within us that the distortion occurs. This does not stop us from investigating why Bacon chooses certain means of representation over others, to address this we must firstly understand the effect that the distortion of norms has on an observer.

Velazquez's portrait of Innocent X Study after Velazquez's portrait (1650) of Innocent X (1953)

Velazquez's portrait of Innocent X Study after Velazquez's portrait (1650) of Innocent X (1953)

Two characteristics of distortion in Bacon’s early portraiture are particularly apparent; the omission of eyes and the expressive mouth. If the eyes are the windows to the soul, than Bacon’s subjects have no souls. The lack of eyes has an immediate dehumanising effect; “wholeness of the personality disintegrates” (Ficacci, 2006, p. 72). In any human interaction, the eyes serve as a focal point for the participants visual attention; this has been shown in many modern eye tracking experiments (e.g. Henderson, Falk, Minut, Dyer, & Mahadevan, 2000). When viewing Bacon’s art the observer’s eyes are left searching the canvas for an alternative focal point of attention, this is provided in an eerie fashion by the mouth. A detailed depiction of teeth, and sometimes tongue, tend to be offset by thin lips. The expressions give the portrait an emotion which is rendered animalistic through the lack of eyes. A final tool was used by Bacon to ensure the observers discomfort; a pane of glass. Nearly all his paintings were behind glass, this is not a common feature of great works of art due to the reflectance of light caused by the glass. However this may be the very reason that Bacon insisted on the glass cover, it gives an added discomfort to the viewer of seeing their own reflection in the paintings (Ficacci, 2006, p.72). Since Bacon’s paintings were frequently commentaries on the human condition, you, the observer, are brought into the paintings, close enough to smell the mortality. As Bacon himself said;

Three studies of the human head (1953) Fine arts and projects, Mandrisio

“The greatest art always returns you to the vulnerability of the human situation” (Hicks, 1989, p. 28). Now that we have a comprehension of the effect of his art, we are in a better position to analyse the psychological motivation for the distortion of the face.

Bacon’s conscious motivation to distort is firstly discussed, followed an examination of possible unconscious motivations. The face is key to a portrait, the disturbance of the facial features of Bacon’s portraiture communicate a very deep disquiet. As an atheist in a post war world, Bacon lived in a society which grappled to come to terms with the horrors of nuclear holocaust and concentration camps. With no god to appease or displease, he relentlessly roared his message of mortality – wake up and smell the meat! The faces of his portraiture are filled with emotion but devoid of identity. The choice to distort the upper part of the face could have more to do with a pre-occupation with the mouth than a disregard for the eyes and nose. Omitting the eyes and nose forces the observer to focus on the mouth. Bacon’s focus on the mouth may have developed for several reasons. In the early years of his career as an artist he purchased a French book containing illustrations of various mouth diseases. Bacon openly admitted the considerable influence which this book had on him (Calvocoressi, 2006). When this is coupled

Picture of mouth disease (sourced from a book bought by Bacon c1928)

with the fact that Bacon had sinus problems in his childhood and underwent an operation on the roof of his mouth in the mid-1930s, it is easier to see why he may have been preoccupied with the mouth (Ficacci, 2006). Of course it is of special significance in its own right; the mouth is a gateway to the senses, it is potentially a weapon, a means of communication, and even a sexual tool. In short, the mouth serves as a reminder of many of our human drives. The mouths which he depicts are distorted both physically and emotionally. Perhaps Bacon considered distortion to be the only lens with which it was possible to view a distorted, modern world. Following the horrors of the war, society was left to grasp for meaning, Bacon remorselessly strips humanity of its frills in an audacious reminder that we are all animals after all. Or as Bacon himself put it; “We are born and we die, but in between we give this purposeless existence a meaning by our drives” (Sylvester, 1996, p. 133).

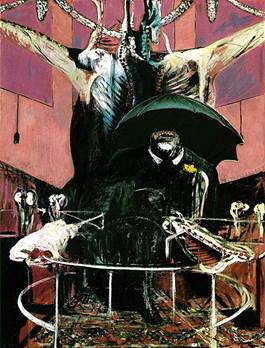

Figure with Meat (1954) The Art Institute of Chicago

Theorizing Bacon’s unconscious motivations for distorting the faces of his subjects is veritable goldmine for psychoanalysts and a minefield for legitimate academics. In addressing the issue we will firstly examine possible motives based on the theories of the two most widely recognized (and widely debunked) psychoanalytic theorists; Freud and Jung, before tentatively forwarding our own hypotheses. Freud’s early theories on art were outlined in General introduction to psychoanalysis (1917), the artist was seen as a near neurotic who had failed to gain success elsewhere in life and so created fantasies in which their wishes (largely sexual) could be expressed. In later theories, Freud recognized the necessity for a good artist to maintain contact with reality and combine this with their neurotic fantasies. These later theories saw the artist as having insights into the human mind, similar to those of a psychoanalyst (Spector, 1972, p. 77-78). Freud would have had a field day with Bacon. His homosexuality, his childhood cross dressing, his lack of formal schooling, and particularly his self confessed sexual attraction to his father, would certainly give Freud a rich array of potential unconscious motivations which were expressed in Bacon’s artwork. There is no doubt that his paternal relationship and his homosexuality had a significant impact on his life works, and found expression in the dark and ominous

Head 1 (1949) Belfast, Collection Ulster Museum

overtones present in the majority of his works. Bacon also had several insights into the base nature, isolation and despair that can haunt the human mind. However, it would be a discredit to the artist to imply that the profound commentaries on the human condition found in his work are merely the product of certain hardships. Many people have suffered far greater but produced no masterpieces. The theories of Carl Jung may have greater relevance to this artist. Given Jung’s preoccupation with symbolic meaning it is not surprising that he has wider spanning theories of art, even going so far as to write about distortion within art. Jung saw the distortion of beauty in art as a consequence of the destruction of the personality. According to Jung, the distortion of art is not an expression of the destruction of the artist’s personality, rather the artist finds the unity of his artistic personality in destructiveness. This theory offers a closer fit to the Pandora’s Box of Bacon’s unconscious mind. Long before Bacon’s work was commercially successful he chose to paint in this unique macabre manner, it must have been reinforced in some

Two figures (1953) Private Collection

Manner other than monetary gain, potentially it allowed him to express his darkest private thoughts in a public, open manner – catharsis for the unconscious mind.

When one comes to view the art of Francis Bacon it is clear that it contains a deep rooted aggression. The snarling, carnal, dehumanised subjects are not the product of a mind at ease. Bacon’s life was spent on the periphery of society, his expulsion from his family, rejection of religion and his homosexuality meant that he was frequently the dispassionate observer of the human race. Like a zoologist living in a colony of civilised monkeys, Bacon thrilled in the opportunity to strip his companions of their illusions. However, his removal from society did not give Bacon an objective viewpoint, it is our opinion that Bacon saw far too much of the underbelly of society, was he born in modern day San Francisco the artist would have had a very different perspective on his fellow man. Nevertheless one must have great respect for the audacity and courage of this artist. Bacon fought with many demons and in the end he conquered them by locking them in paint, or as Damien Hirst put it: “Bacon’s got the guts to fuck in hell” (Burn, 2001).

Head IV (1949) London, Arts Council Collection, Hayward Gallery

To conclude, it is worth bearing in mind that when we analyse this art, there are three degrees of separation between what we perceive and the subject that Bacon chose to paint. The first degree of separation occurs in Bacon’s own mind where his brain actively binds the information relating to his subject supplied to him from both his sensory and memory systems. Bacon chose an appropriate manner of depicting his subject, or, as was often the case, the manner of depiction was actively reached during the painting process. As we have seen from his art, there was often little relation between the subject matter and the representation which Bacon chose for it. The second degree of separation occurs between that which Bacon means to mark on the canvas before him, and that which ends up marking the canvas. Bacon was notorious for destroying his own works with which he was dissatisfied, once going so far as to buy one of his paintings at an exhibition only to destroy it. The third degree of separation occurs between that which is on the canvas and that which an observer perceives, which once again must be filtered through a biased system of perception and bound with information stored in memory. So when we come to look at great art, and analyse the meanings and motivations contained within it, we might as well be analysing the meanings and motivations contained in a murky mirror.

Study For A Portrait (1952) London, Tate

Reference Section

Burn, G. (2001, October 8) Hirst on Francis Bacon. The Guardian.

Calvocoressi, R. (2006) Francis Bacon embalmed. The Times.

Cronin, A. (2000) Life Works. The Guardian.

Davidson, G (Sr. Ed.). (2006). Collins English Dictionary. London: Collins.

Ficacci, L. (2006) Bacon Germany: Taschen

Francis Bacon (painter). (2008, February). Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Retrieved February 21, 2008, from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Francis_Bacon_(painter)

Hicks, A. (1989). The School of London: the resurgence of contemporary painting. London: Phaidon.

Henderson, J., Falk, R., Minut, S., Dyer, F., & Mahadevan, S. (2000). From Fragments to Objects: Segmentation and Grouping in Vision. Amsterdam: Elsevier

Spector, J. (1972) The aesthetics of Freud. London: Penguin Press.

Sylvester, D. (1987) Interviews with Francis Bacon. New York: Thames & Hudson.

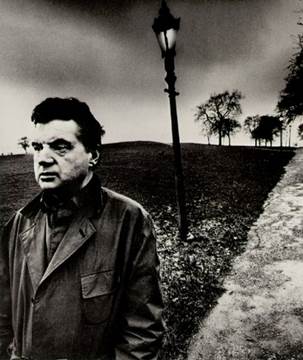

Portrait of Francis Bacon by Bill Brandt

Received: January 29, 2014, Published: February 20, 2014. Copyright © 2014 Stephen Quigley and Mark A. Elliot