Mother-Daughter Ambivalence According to Sigmund Freud and Chantal Akerman

by

Missy Molloy

December 14, 2014

Freud’s defensive stance toward female psychosexual development has two clear sources: one, his sensitivity to feminist critiques; and two, his awareness that female sexuality remained slippery despite his sustained effort to incorporate it into his major theories. Like the psychoanalytic process, which brings patients into direct contact with areas of psychic tension, Freud’s writings on female sexuality expose the theoretical ambiguities that continue to complicate cultural analyses oriented by gender. This essay reads Freud in conjunction with representations of the mother-daughter relationship in several films by Chantal Akerman, which affectively render the ambiguity Freud diagnosed in that often-fraught familial bond. In the process, I employ an analytical approach that integrates aesthetic and psychoanalytic theories, a combination I consider productive in relation to 21st century culture, which defines itself as sexually progressive while avoiding significant blind spots that make widely-circulated notions of gender equality ring hollow.

Mother-Daughter Ambivalence According to Sigmund Freud and Chantal Akerman

Missy Molloy, University of South Florida

Freud’s defensive stance toward female psychosexual development has two clear sources: one, his sensitivity to feminist critiques; and two, his awareness that female sexuality remained slippery despite his sustained effort to incorporate it into his major theories. Like the psychoanalytic process, which brings patients into direct contact with areas of psychic tension, Freud’s writings on female sexuality expose the theoretical ambiguities that continue to complicate cultural analyses oriented by gender. This essay reads Freud in conjunction with representations of the mother-daughter relationship in several films by Chantal Akerman, which affectively render the ambiguity Freud diagnosed in that often-fraught familial bond. In the process, I employ an analytical approach that integrates aesthetic and psychoanalytic theories, a combination I consider productive in relation to 21st century culture, which defines itself as sexually progressive while avoiding significant blind spots that make widely-circulated notions of gender equality ring hollow.

The Chantal Akerman films discussed below uncannily reflect the contradictions that frustrated Freud, and I’ll demonstrate that they also contribute new information in the form of affective visuals that advance Freud’s theories. Besides the fact that is well-worn territory, analyzing Freud for evidence of phallocentrism and latent misogyny seems both a reduction of his work and a missed opportunity. My intention is not to refute or replace Freud’s theories but to explore intersections between his work and these films in order to complicate both for productive purposes.

Freud’s “Two Tasks”

“A comparison with what happens with boys tells us that the development of a little girl into a normal woman is more difficult and more complicated, since it includes two extra tasks, to which there is nothing corresponding in the development of a man . . . In the course of time, a girl has to change her erotogenic zone and her object—both of which a boy retains. The question then arises of how this happens: in particular, how does a girl pass from her mother to an attachment to her father? Or, in other words, how does she pass from her masculine phase to the feminine one to which she is biologically destined?” (Freud on Women 346-348)

Freud identifies two tasks that a woman has to accomplish in order to achieve “normal” femininity: her main erogenous zone must shift from clitoris to vagina and she must transfer her primary sexual attachment from her mother to her father (and thus overcome her original homosexuality). Freud uses these tasks to adapt female sexuality to fit his Oedipal frame; however, he is well aware that this adjustment is far from seamless—an awareness that casts doubt on his use of the word “normal” to describe the “final” stage of feminine sexuality, which centers on vaginal, heterosexual pleasures.

His language often reveals hesitation about the conclusions he draws, and he seems dissatisfied by the ease with which female sexuality can develop along other paths than the one he identifies as “normal”: “The development of femininity remains exposed to disturbance by the residual phenomena of the early masculine period. Regressions to the fixations of the pre-Oedipus phases very frequently occur . . . Some portion of what we call ‘the enigma of women’ may perhaps be derived from this expression of bisexuality in women’s lives” (359; emphasis added). His pejorative language indicates his disapproval of these alternative developments, including one that leads to “sexual frigidity” and another to “a manifest masculinity complex” and homosexuality. However, his “third path,” the one he categorizes as normal, involves complex psychic maneuvers that sound far from natural.

Despite the complications this third path introduces into Oedipal theory, Freud tries hard (and with admirable commitment) to make female sexuality complement his formulation of male sexual development: “Only if her development follows the third, very circuitous, path does she reach the final normal female attitude . . . Thus in women the Oedipus complex is the end-result of a fairly lengthy development” (327). Because Freud recognized that the path he proposed was “circuitous” and “lengthy,” he emphasized the importance of the “pre-Oedipus phase” of female development, which allowed him to attribute some ambiguities of his female Oedipus complex to this earlier, enigmatic stage.

Three conclusions from “Female Sexuality” demonstrate the critical role the pre-Oedipus phase plays in Freud’s account of female sexuality (by the early 1930s): one, that the attachment to their mothers “possesses a far greater importance” than for males (327); two, that “the girl’s final hostility” toward her mother is excessive (331); and three, that her “intense attachment to her mother is strongly ambivalent and . . . it is in consequence precisely of this ambivalence that her attachment is forced away from her mother” (332). Ambivalence is the crux of his proposition because it enables him to reconcile the paradox of his first two conclusions. Whereas the original erotic zone and object remain the same for boys, girls, in the course of performing the two “necessary” sexual transfers, must turn away from the mothers to whom they had been intensely attached. Freud relies on the term “ambivalent” to explain the intensity of her affection and its conversion into hostility, and in the process, he concludes that this contradictory emotional response is an essential rather than a secondary social process.

Two early films by Chantal Akerman, Les rendez-vous d’Anna (1978) and News from Home (1976), explicitly evoke the pre-Oedipal attachment to the mother and explore its impact on adult female sexuality. Les rendez-vous d’Anna presents a series of encounters between Anna (played by Aurore Clément), who is traveling from Germany to France promoting her films, and five people: two strangers, the mother of her childhood friend and ex-fiancé, and the two people she is most intimately connected with—her mother and her most consistent lover, Daniel. Akerman stresses Anna’s aloofness from the people she encounters; as she listens intently to their monologues that awkwardly combine banal details of their lives and extremely personal information, she remains emotionally distant. Anna exposes herself only in two specific moments: when she describes (in her own monologue) a lesbian affair to her mother and when she sings a song to Daniel about intense love that ends in suicide.

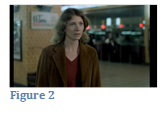

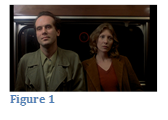

Les rendez-vous d’Anna’s five encounters are structured to emphasize her fourth encounter with her mother. Ambivalence is defined as “the coexistence in one person of contradictory emotions or attitudes (as love and hatred) towards a person or thing” (“Ambivalence”). In the threads that connect the five encounters, Akerman suggests that Anna’s ambivalence toward her mother informs all of her relationships. Aurore Clément’s face consistently conveys alienation while also revealing, regularly if inconsistently, a desperate desire for intimacy. Two images indicate her emotional range in the film from remote (figure 1) to vulnerable, as in the image on the right (figure 2), which conveys Anna’s surprised recognition of her mother from a distance. In this particular shot, the camera remains focused on Anna’s face for approximately ten seconds while her expression serially registers surprise, apprehension, and desire.

Les rendez-vous d’Anna’s five encounters are structured to emphasize her fourth encounter with her mother. Ambivalence is defined as “the coexistence in one person of contradictory emotions or attitudes (as love and hatred) towards a person or thing” (“Ambivalence”). In the threads that connect the five encounters, Akerman suggests that Anna’s ambivalence toward her mother informs all of her relationships. Aurore Clément’s face consistently conveys alienation while also revealing, regularly if inconsistently, a desperate desire for intimacy. Two images indicate her emotional range in the film from remote (figure 1) to vulnerable, as in the image on the right (figure 2), which conveys Anna’s surprised recognition of her mother from a distance. In this particular shot, the camera remains focused on Anna’s face for approximately ten seconds while her expression serially registers surprise, apprehension, and desire.

The prolonged focus on Anna’s face establishes this meeting’s primacy, while Anna’s expression offers viewers a potential explanation for the emotional detachment she usually evinces. During the first three encounters, her emotional distance rarely wavers even when she verbally expresses sympathy for the speaker. Her expression while she gazes at her mother from across the station connotes emotions barely hinted at in her previous encounters. Structurally, the fourth and fifth encounters retroactively shed light on Anna’s inaccessibility during the prior meetings. By stressing that the encounter with her mother affects Anna most, Akerman suggests that her relationship with her mother is the source of Anna’s opaque emotions and their dramatically uneven distribution. In addition, Akerman incorporates several strategies to explicitly link Anna’s unusual affect to her sexuality: first, by having Anna attempt and fail to reach her female lover by phone several times throughout the film; second, by showing Anna narrate her lesbian sexual encounter to her mother while they are laying together naked in a hotel bed; and third, by following the emotionally-charged meeting with her mother with the one between Anna and Daniel. I interpret the sequence as far from arbitrary, even though Akerman doesn’t explain the order in an obvious way. She does, however, shift the emphasis from Anna as passively receptive, yet disinterested in early encounters to vulnerable and confused in her meetings with her mother and Daniel. Akerman punctuates the different emotional register of these final encounters by choreographing Anna’s orientations to her mother’s and then Daniel’s bodies according to her ambivalence toward them. For instance, the long take of Anna and her mother’s slow approach from opposite directions and their passionate embrace recalls romantic conventions, but their subsequent appraisal of each other connotes restraint and unease.

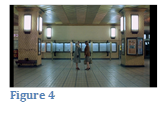

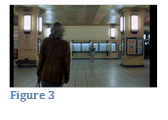

Immediately after the long take I described above, of Anna’s face in close up observing her mother across the train station, their simultaneous approach is shot first from Anna’s perspective, which stresses the space around them rather than the diminishing distance between their bodies (figure 3). Next, instead of moving closer to their bodies once they embrace, Akerman maintains the long shot as the two distant figures meet slightly off-center in the frame. Then, filmed in profile and from the same distance, their bodies are close but no longer touching (figure 4). Because Akerman avoids the conventional tendency to move the camera closer to the characters to augment their intense emotions, she cultivates an ambiguous dynamic between the two characters. Anna’s desire is conveyed via her expression in close up, but their physical contact is presented from a far distance. This aesthetic choice is crucial because it combines a desire for intimacy with distance. In other words, an intense attachment can manifest in emotional distance: that disjunction informs Freud’s account of the normal development of the mother-daughter bond and Akerman’s depiction of Anna’s relationship with her mother. Akerman’s compositions and staging thus reflect the ambivalence of the emotional encounter along with its intensity and anxiety.

Immediately after the long take I described above, of Anna’s face in close up observing her mother across the train station, their simultaneous approach is shot first from Anna’s perspective, which stresses the space around them rather than the diminishing distance between their bodies (figure 3). Next, instead of moving closer to their bodies once they embrace, Akerman maintains the long shot as the two distant figures meet slightly off-center in the frame. Then, filmed in profile and from the same distance, their bodies are close but no longer touching (figure 4). Because Akerman avoids the conventional tendency to move the camera closer to the characters to augment their intense emotions, she cultivates an ambiguous dynamic between the two characters. Anna’s desire is conveyed via her expression in close up, but their physical contact is presented from a far distance. This aesthetic choice is crucial because it combines a desire for intimacy with distance. In other words, an intense attachment can manifest in emotional distance: that disjunction informs Freud’s account of the normal development of the mother-daughter bond and Akerman’s depiction of Anna’s relationship with her mother. Akerman’s compositions and staging thus reflect the ambivalence of the emotional encounter along with its intensity and anxiety.

The specific causes of a daughter’s hostility toward her mother perplexed Freud considerably. He proposes the girl’s resentment about her lack of male genitals as one potential cause, and the girl’s suspicion that her mother “did not give her enough milk” as another, but the only conclusion he settles firmly on is “that the little girl’s attachment to her mother is strongly ambivalent, and that it is in consequence primarily of this ambivalence that . . . her attachment is forced away from her mother” (332). Akerman’s approach to the mother-daughter relationship exhibits the same incomplete logic. Like Freud, Akerman does not provide a solid rationale for the ambivalence, but unlike Freud, she does not seem concerned about the cause of her character’s complicated emotional response. Instead, she offers this simultaneous attachment and resistance as the foundation of Anna’s ways of interacting with other people.

Released a year before Les rendez-vous d’Anna, News from Home uses distinctly different cinematic strategies to express the ambivalence of mother-daughter relations. An autobiographical film composed of long takes and slow pans of New York City, the images convey a sense of alienation from the urban scenes whether the camera captures the early-morning stillness of lower Manhattan (figure 5) or the contained chaos of a crowded subway car (figure 6). The sound of Akerman reading letters her mother sent from Europe while Akerman lived in New York City (from 1971-1972) accompanies the documentary footage of Manhattan. The relationship between the letters and the urban scenes is left open. The shots are not obviously chronological (for example, several long takes of empty, pre-rush hour streets are followed by nocturnal images from the same neighborhood), and no obvious narrative can be applied to either the content or sequence of the long takes. Similarly, the letters are not dated, and the repetitive content of her mother’s messages has a timeless effect; whether or not Akerman reads them chronologically becomes irrelevant in the stagnant mood established by the letters, which suggests that time progresses without effecting remarkable changes.

Her mother’s constant emotional appeals comprise the bulk of the “news” from home. The letters are mainly exhortations that beg Chantal to write more often by continually emphasizing the crucial role Chantal’s letters play in her life. They also express anxiety about Chantal’s situation in New York in a manner that is both solicitous and overtly manipulative:

Her mother’s constant emotional appeals comprise the bulk of the “news” from home. The letters are mainly exhortations that beg Chantal to write more often by continually emphasizing the crucial role Chantal’s letters play in her life. They also express anxiety about Chantal’s situation in New York in a manner that is both solicitous and overtly manipulative:

Sweetheart, I just sent some summer clothes to the last address you sent. Why did you move? I hope you get the package soon. It takes a week. I paid the postage. I hope you won’t owe anything. It’s complicated to send packages, so if you need anything, I’ll include some dollars in my letters. I hope it’s not too hot. I know sunny weather depresses you, and you don’t even have any sandals. I’m sure there must be good ones you can buy there. I hope you get through the summer all right. Sweetheart, at first you wrote so often. Now I’m only getting one letter a week. Make the effort to write. You can’t imagine how much your letters cheer me up . . . Please write soon.

The letters are remarkably uniform. Her mother mixes different types of information without an overt pattern; one detail simply leads to another in an associative process that would confuse viewers who weren’t extremely familiar with this type of discourse. For example, take the first few sentences: “Sweetheart, I just sent some summer clothes to the last address you sent. Why did you move? I hope you get the package soon.” The first sentence is informative; it lets Chantal know that a package is coming. Her question is inquisitive and could also be interpreted as manipulative because it directly follows the information about the gift in the mail, which seems at least partially intended to promote gratitude. Her next statement (“I hope you get the package soon”) appears disingenuous in relation to the question—as if “hope” that the package arrives “soon” is meant to offset the invasive aspect of the question, a conclusion strengthened by her injunction to write later in the letter: “Make the effort to write.” In the collage-like composition of the letter, this demand is the most direct, which suggests that it is the main motivation for writing; in light of this conclusion, the other information indirectly supports this request. Many of her statements that express concern for Chantal are significantly undercut by her mother’s continual emphasis of the difficulty helping her daughter entails: “It’s complicated to send packages, so if you need anything, I’ll include some dollars in my letters.” These offers to help expose the mother’s desire to be needed; they are also compounded by the mother’s need for her assistance to be appreciated. Her appeal is based on the following formula: I’ll provide x if you ask me, but in order to ask, you have to write. And the help offered comes with strings attached; she expects gratitude and more regular contact in return. The letter’s ulterior motive is to convince Chantal, through various persuasive methods, to write, and to write often.

The impact of the letters relies upon the familiarity of the content, not only to their recipient but also to viewers. A review posted on the website “Strictly Film School” describes the letters as “maternally manipulative,” a phrase that suggests an intimate correspondence between the two terms—as if there is a special category of manipulation practiced mainly (or only) by mothers (Strictly Film School). News from Home exploits the widespread familiarity of “maternal manipulation” in order to indirectly express Chantal’s ambivalence about the letters. A female figure barely discernible in a dark subway window literalizes the daughter’s response to the pressure of her mother’s affections (figure 7); the constant, undifferentiated emotional appeals erase her identity, her sense of herself as distinct. The film promotes and sustains the daughter’s ambivalence without offering any directions regarding what to do with these confusing emotions. By intimately connecting her mother’s charged appeals to the camera’s steady, impervious gaze, Akerman creates an affective atmosphere that uncannily overlays foreignness and the familiar space of maternal discourse.

The impact of the letters relies upon the familiarity of the content, not only to their recipient but also to viewers. A review posted on the website “Strictly Film School” describes the letters as “maternally manipulative,” a phrase that suggests an intimate correspondence between the two terms—as if there is a special category of manipulation practiced mainly (or only) by mothers (Strictly Film School). News from Home exploits the widespread familiarity of “maternal manipulation” in order to indirectly express Chantal’s ambivalence about the letters. A female figure barely discernible in a dark subway window literalizes the daughter’s response to the pressure of her mother’s affections (figure 7); the constant, undifferentiated emotional appeals erase her identity, her sense of herself as distinct. The film promotes and sustains the daughter’s ambivalence without offering any directions regarding what to do with these confusing emotions. By intimately connecting her mother’s charged appeals to the camera’s steady, impervious gaze, Akerman creates an affective atmosphere that uncannily overlays foreignness and the familiar space of maternal discourse.

In conjunction, the two layers of New From Home’s narration—the letters read in voiceover and the impersonal views of the city—perfectly express the dual meaning of heimlich, which Freud famously scrutinizes in The Uncanny; what the letters’ familiar content conceals is the recipient’s sense of alienation from what is supposedly familiar. In developing his notion of the uncanny, Freud focuses on the complex relationship between the two German terms, heimlich and unheimlich. What fascinates Freud about these superficially opposite terms is the fact that they are not seamless inversions of one another; the definition of heimlich contains aspects of unheimlich, which suggests that their relationship is ambiguous rather than antonymic:

Among its different shades of meaning the word ‘heimlich’ exhibits one which is identical with its opposite, ‘unheimlich’ . . . the word ‘heimlich’ is not unambiguous, but belongs to two sets of ideas, which, without being contradictory, are yet very different: on the one hand it means what is familiar and agreeable, and on the other, what is concealed. (The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud 223)

The maternal discourse foregrounded in News from Home illustrates the key features of heimlich as defined by Freud: “Thus heimlich is a word the meaning of which develops in the direction of ambivalence, until it finally coincides with its opposite, unheimlich. Unheimlich is in some way or other a sub-species of heimlich” (225). By using impersonal images of a foreign city to complement the letters, Akerman animates the uncanny aspects of maternal discourse.

The letters’ cyclical, repetitive rhetoric initially invites viewers to experience the “familiar,” “intimate,” and “tame” aspects of heimlich; however, prolonged exposure to this familiar communicative mode pushes viewers towards experiences of unheimlich, “‘the name for everything that ought to have remained … secret and hidden but has come to light’” (223). By isolating a discursive mode that usually only plays a supporting role in feature-length films, Akerman foregrounds the uncomfortable affect of a type of communication so familiar that its specific properties are often overlooked. The structure of News from Home simply and eloquently communicates Freud’s insight about heimlich, that it “belongs to two sets of ideas, which, without being contradictory, are yet very different.” Freud’s conclusions about the uncanny have been frequently integrated into film analyses, but the emphasis is most often on his idea that the uncanny “arouses dread and horror” (219). Consequently representations of maternity as monstrous receive the most ciritcal attention.[i] Akerman’s innovation is to represent maternity not as monstrous, but as utterly commonplace—predictable and mundane. By avoiding spectacle, Akerman taps into the subtle discomfort of maternal discourse and prolongs it; therefore, she invites viewers to carefully reflect on the complicated effects of maternal attention, which can simultaneously inspire opposing emotions.

Akerman’s films draw viewers in and keep them at a distance, mimeses of maternal gestures. The ambivalence of the mother-daughter relation frustrated Freud’s attempts to explain female sexual development, and one could argue that his inability to convincingly theorize female sexuality crucially impacted his theoretical trajectory and his late work on the drives, for instance in Beyond the Pleasure Principle. His perplexity about the exceptions to the pleasure principle resembles his confusion about women’s ambivalent emotions toward their mothers. Her early attachment to her mother introduces her to desire, yet she must reject her mother in order to become normal. In An Outline of Psycho-Analysis, Freud outlines the mother’s role as the child’s first erotic object: “By her care of the child’s body she becomes its first seducer. In these two relations lies the root of a mother’s importance, unique, without parallel, established unalterably for a whole lifetime as the first and strongest love-object and as the prototype for all later love-relations—for both sexes (Freud on Women 364). Les rendez-vous d’Anna and News from Home approach a mother’s influence on her daughter differently than Freud because, without identifying its intense ambiguity as negative, the films stress that daughters’ perceptions of the external world are constituted, and indeed haunted, by their contradictory feelings for their mothers, their first, discarded love-objects.

Works Cited

Akerman, Chantal, dir. Les rendez-vous d'Anna. Paradise Films, 1978. Film.

---. News from Home. Paradise Films, 1977. Film.

“Ambivalence.” Oxford English Dictionary. 2013. Web.

Creed, Barbara. The Monstrous-Feminine: Film, Feminism, Psychoanalysis. New

York: Routledge, 1993. Web.

Freud, Sigmund. Freud on Women. Ed. Elizabeth Young-Bruehl. New York: Norton

& Company, 1990. Print.

---. The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud. Ed.

James Stratchey. London: Hogarth Press, 1974. Web.

[i] Cinematic scholarship on the horror genre most often integrates ideas from The Uncanny to address representations related to femininity and maternity. A classic example is Barbara Creed’s The Monstrous-Feminine: Film, Feminism, Psychoanalysis.

Received: November 4, 2014, Published: December 14, 2014. Copyright © 2014 Missy Molloy