Situating the "Real," Discovering Desire

by

Lesley Marks

July 9, 2011

Gerhard Richter grew up during the war and Soviet occupation of East Germany. After working briefly in the East, he moved to the West in 1961 to develop his career as an artist. I examine Richter’s work through the prism of Lacanian theory. Lacan recognises humanness in the dialectical relations between the eye and the gaze: it is our need to see and be seen (recognised) that differentiates us from the animal world. Similarly, Richter’s paintings-from-photographs address the impossibility of piercing the surface of another’s gaze; he paints representations that ask questions, yet give no answers. Lacan and Richter both cast doubt on the notion of ‘truth’ and express the tension between truth and appearance, seeking to better understand the desire and lack that characterise the way human beings relate both to themselves and others. Richter’s paintings are a dialectization of the Lacanian ‘real’, attempting to speak the unspeakable and come to terms with its impact.

Introduction

What follows is a study of some of Gerhard Richter’s paintings-from-photographs, analysed through the lens of Lacanian psychoanalytic theory. I have juxtaposed the artist and the psychoanalyst for a number of reasons, not least because both had tremendous impact on cultural theory and fine art respectively from the mid-twentieth century. Lacan’s psychoanalytic work is – as his biographer Elisabeth Roudinesco explains –“treated as if it were holy writ”[1] in the French psychoanalytic movement, though in English-speaking countries he was seen more as a French philosopher than as the author of a clinical doctrine[2]. But English-speaking writers like Hal Foster and Judith Butler use Lacanian theories to pursue a wide variety of arguments ranging from art criticism and film studies to feminism and gender studies.

Richter’s impact on the world of fine art is harder to measure, partly because he is still alive, and still painting and exhibiting new works. However, since the 1960s Richter has become known for his complexity and range of styles. The scope Richter embraces leads him to be described by one of the National Portrait Gallery’s critics as “one of the world’s leading contemporary artists”[3]. This study is concerned with paintings-from-photographs, but it must be noted that Richter’s oeuvre includes thousands of works and the examples shown here constitute only a small measure of his output.

Both Lacan and Richter address the issues of desire and lack. In Lacan these have almost ontological status: “Once the subject himself comes into being, he owes it to a certain nonbeing [lack] upon which he raises up his being [desire]”[4]. The Lacanian subject’s desire is unattainable; it eludes him and he lives his life within the context of the lack. In Richter the viewer is presented with a view of her desire which is subsequently negated through a system of painterly techniques, such as blurring and wiping. His work can be described as underscoring the human dilemma of our desire to understand the world and our place within it, yet being denied the comfort of enjoying any certainty about our knowledge.

In addition, both analyst and artist ask us to locate the ‘real’. The ‘real’ has different meanings for Lacan and for Richter. In Lacan the ‘real’ is an “unrent, undifferentiated fabric”[5]; there are no divisions or gaps in his ‘real’ register as it belongs to the period before language and the ‘symbolic’ order, and equates to the time before the baby’s body was socialised and coaxed into compliance. The ‘real’ in that sense does not exist – it is “killed” by the letter of the ‘symbolic’ order which, as Bruce Fink puts it, “cuts into the smooth facade of the ‘real’, creating divisions, gaps and distinguishable entities... laying the ‘real’ to rest”[6]. Lacan borrows from Heidegger when he says that the ‘real’ “ex-ists” outside of our reality; it only exists insofar as we use language to describe it and give it a sort of substance.

Richter questions what is real in his painting-from-photographs, a medium which also links him to Lacan. The photograph captures a subject which is irreproducible and unsymbolisable; it is “killed” by the act of capture in the frame[7]. Thereafter it exists as a thing-in-itself, as something in the register of the ‘real’. It symbolizes nothing other than its own referent. The only way, then, to make a photographic image a symbol of something is to re-create it, re-frame it and re-represent it. Recreating, reframing and representing is the business of Gerhard Richter.

By bringing together the artist and the psychoanalyst, I am using one to better understand the other. Both express the tension they perceive between ‘truth’ and appearance, and both explore the ways in which human beings relate to themselves and to others. I propose that Richter and Lacan are mutually reinforcing: Richter deals with the visual, Lacan with the spoken; each questions what we see and what we say, asking what is real and what is predicated on what we desire and what we lack. There is no unitary concept of ‘reality’ as such either for Richter or Lacan: there is a tension between reality and illusion that needs to be worked through in order for the subject or the viewer of the painting to gain new knowledge.

Lacan questioned the notion of truth or authenticity in language and in what we see, as he makes clear in his description of the ‘imaginary’ order and his claim that: “In this matter of the visible, everything is a trap”[8]. Similarly, Richter questioned our understanding of what we see when we view an object – and what is involved in the process of ‘apprehending’. The ‘imaginary’ order is relevant to both – we look to see what we desire and we don’t find it. I will endeavor to show that both analyst and artist propose that the perceiving subject is deceived, or that she deceives herself as a result of her desire.

Memory

Richter’s early photo-paintings can be understood as having been executed by a Lacanian ‘divided subject’, an artist who is other to himself. Between 1962-1965, he created a series of works which relate to his family during the war: his mother’s adored brother Rudi who was killed in the early weeks of the war (Fig.1); the artist being held by his retarded Aunt Marianne, who was later killed in a Nazi euthanasia camp (Fig.2), and several paintings of military aircraft which recall how close Richter was to the bombing of Dresden as a young boy (Fig.3 is one example of this series). Yet Richter treated these war-related topics with complete neutrality, claiming to believe in nothing and calling the works meaningless. In an interview in 2002 with Robert Storr, Richter recalled that the events of the war and the atrocities of the Holocaust were not a topic of open discussion in the early 1960s in Germany, and artists and the viewing public were “unable to see the statement in the work… We rejected it; it didn’t exist… You could only take it as a joke”[9]. However, Richter painted several versions of Uncle Rudi and many different types of warplanes – mostly those used by the anti-German Alliance. This repetition is a signature feature of his work. He often repeats an image

Fig 1: Uncle Rudi, 1965 Fig 2: Aunt Marianne, 1965 Fig 3: Bomber, 1963

several times, or uses the same subject in different contexts. Lacan discusses repetition in relation to memory and offers us two concepts. The first is Wiederholung - the repetition of the repressed as symptom or signifier, which he calls the automaton. According to Lacan, memory is indestructible: despite Richter’s pronouncements that the paintings held no meaning (“I might have just as well painted cabbage”), and his insistence on having no ideology or beliefs, the signifying chain remembers for him, and these images with their painful memories emerge in his early paintings.

These images from childhood link to the Lacanian claim that repetition is the resistance of the subject against the hors-signifie – or what Lacan later calls “objet a”. In addition to avoiding objet a, the subject also avoids any primal feeling of pleasure or pain associated with it and the relationship to objet a is characterised by primal feelings of disgust or aversion, as in hysteria, or a sense of being overwhelmed and the need to avoid, as in obsession[10]. The act of repetition, then, can be linked to avoidance of an aspect of the ‘real’.

Parenthetically, we might ask why Richter chose to paint Rudi, his father’s brother, and not his own father who also returned home a defeated Nazi soldier; and why he felt compelled to paint himself with his very young Aunt Marianne so many years after her murder by the Nazis? Can we read a desire to recapture a sense of pre-war family unity; a dreamed-of golden period which reflects the misrecognised specular image of the baby who sees himself in the mirror?

The second kind of repetition-as-memory is Wiederkehr – the repetition of a traumatic encounter with the ‘real’, something that resists the ‘symbolic’ and which is not a signifier at all. Lacan calls this the tuché. We see an example of Wiederkehr in the series of paintings titled 18 October 1977, which present the protagonists of the Baader-Meinhof Group who were found dead in their cells under suspicious circumstances.

Fig.4: Confrontation 3, 1988 Fig.5: Dead, 1988 Fig.6: Man Shot Down 2, 1988

Baader-Meinhof arose partly out of the failed de-Nazification programme in post-war Germany, and the attempt to deal with feelings which arose from the previous generation’s refusal to acknowledge the collective guilt of the holocaust and atrocities perpetrated by Nazi ideology. The generation born during and after the war was left to name the horror and deal with it.

A decade after their deaths, Richter treats the protagonists of this series in a way which is both affectless and affective, repeating each person’s image several times. There is in the stories of these comrades-in-arms an unassimilable, unsymbolisable content which Richter describes by means of repetition and by use of the colour grey which he calls the colour of no-thing – nothing being the affectiveless views of these people as seen in press photographs, or the no-thing they are as Lacanian subjects who have been eclipsed by language. Their names (signifiers) now point to dead people or to “terrorists”, nothing more. The people they were, their ideas, dreams and aspirations have been killed both by the language of the press which defined them collectively as “terrorists” and by their deaths which are shown as traumatic. Paradoxically and typically in Lacanian terms, Ulrike Meinhof, Andreas Baader and Gudrun Esslin fall beneath the signifier “terrorist”, and they no longer exist.

The images work like the Lacanian screen that both protects from, and yet forces an encounter with, the traumas of childhood (the tuché). Richter’s paintings may be understood as a dialectization of the Lacanian ‘real’ and, as such, reflect an attempt to speak what was then unspeakable, and to come to terms with its impact.

The blurring of the portraits is a typical Richterian technique. It may be taken to signify the blurring of memory, of the blurring of truth – for example, by the press and police whom many claimed were responsible for the deaths of these young revolutionaries. The blurring is also a painterly technique which forces us to look and look again, to try to refocus, or verify what it is we see. This is close to the Lacanian demand that we listen more carefully to what we say and what we hear: there are no truths on which we can rely in Lacan, just as there are no truths contained in the works of Richter. Neither offers us a god to take our troubles to: the viewer, like the analysand, has to ask herself again and again what it is she sees and hears, and why and for whom she acts as she does.

Symbolising Desire and Lack

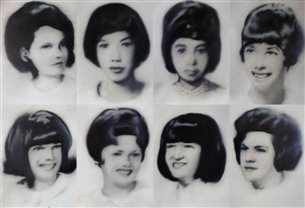

Fig.7: Eight student nurses

Fig.7: Eight student nurses

Above is Richter’s re-creation of eight student nurses, brutally murdered by Richard Speck in Chicago in 1966. Richter takes the trouble to re-make the image from the contemporary press as a painting comprising eight separate canvases which are then re-situated together as a group. This allows him to highlight the way in which the nurses’ individuality was erased in the police files and press photos. The fact that the news of their deaths was reported under the headline “eight student nurses” fixes the girls in a death-like pose; the language of the title “eight student nurses” reduces the subjects to a signifier and divests them of the true dimensions of their identity.

Richter’s painterly treatment blurs the girls’ individual features thereby further highlighting the negation of identity, though he takes care to differentiate each from the other seven by retaining the shape of each face, the hair and general features. However, it is clear we are viewing a representation: this is not a picture which connotes likeness (like so many traditional paintings of the dead), but a re-presentation of girls who no longer exist. It is this “no-longer-exist” that forms the subject of these paintings, and it is this which becomes the moral of the work.

Death is perhaps the easiest way in which to understand aspects of the Lacanian ‘real’. It is death we ignore throughout much of our lives, avoiding mention of the inevitable as if it will not happen. Lacan joked about the ‘real’ being troumatic (creating a pun on the French word trou meaning ‘hole’). Death is a hole through which we are forced to confront our own mortality. It is the “nothing-left” of the nurses that points up the ontological lack of Lacan.

Roland Barthes reminds us that the referent of a photograph includes an element of death as it contains something which cannot be retrieved. The nurses are ultimately the object lost in the language and media culture of the times. Richter’s ability to re-present them retrieves them in one sense. However, his retrieval might also be seen, in Lacanian terms, as a desire for the lost objet a, which can never be retrieved – in this case, an attempt to negate the particular cruelty of the manner of the deaths and make reparation.

In discussing the gaze, Lacan borrows from Merleau Ponty to establish the subject's dependence for recognition – and perhaps for his very existence – on the fact of being seen or recognised. Thus the dialectic of truth and appearance determines that if I am recognized in the eyes of the other, then I exist. It is this desire to be recognized by the other which distinguishes us as human.

Lacan takes this further, explaining that there is a lure in the relation between the gaze of the other and what one wishes to see; but the subject is seen in a way which falls short of how he wishes to be recognized (seen). Thus the eye – the organ which sees – functions in the same way as Lacan's objet a and, like the phallus, symbolizes a lack.

Richter, too, battles with the question of what it is we see when we look at an object. He says that what he sees is not what any other sees. For Richter, appearance is a “phenomenon”: what is seen is informed by who the see-er is, her life experiences, her own way of understanding the world. So whatever object it is that Richter paints, he is painting it in order to convey the way in which he, Richter, sees it. It is Richter's gaze we are looking at when we look at his paintings. In this respect, he comes very close to Lacan in his understanding of the lack that inheres in the tension between seeing and knowing, as illustrated below.

The painting shown below is of Jackie Kennedy, painted from a 1963 newspaper image of her responding to the news of her husband’s death. Her anonymity is preserved in Richter’s painting by the fact that her name does not appear in the title. This may be Richter’s way of freeing the viewer from the limitation imposed by “knowing”, and thus allowing us to continue the process of trying to fathom the image ourselves. It may also be a way of re-affording her the respect she was not given by the press reporters and photographers at the time.

Fig 8: Woman with umbrella, 1964

Fig 8: Woman with umbrella, 1964

The painting is characteristically blurred, denying the viewer clarity and creating an impressionistic vision of a woman in a very specific gesture of horror. The handkerchief, in particular, recalls the Lacanian stain; it almost looks like a stain on the woman’s heart and is barely recognizable as a handkerchief. Lacan tells us: “…[I]f I am anything in the picture, it is always in the form of the screen, which I earlier called the stain, the spot”[11]. Here Richter’s painting offers up a representation of the concept of the Lacanian gaze. The woman looks at something, but she is also looked at and perceived as a “woman with umbrella”. There is a two-way gaze where neither viewer can fathom what it is she sees: the woman-with-umbrella is in shock and appears paralysed, unable to take in what she has heard or seen. The viewer is left with an unclear image which leaves us somehow dissatisfied – we cannot fathom the pieces of this puzzle: a woman, an umbrella, a handkerchief which appears as a stain on her heart – but we are nevertheless drawn to understand the situation that has given rise to this powerful gesture. The painting becomes a screen on which the image of a subject is projected and which, after typical Richterian treatment, appears more like a “stain” than a figurative likeness. Thus the canvas becomes a site of mediation between artist and viewer: Richter offers something partly or fully unrecognizable; the viewer must work out what it is and, more importantly, what he feels about it. But if we know this is Jackie Kennedy responding to news of her husband’s assassination, we no longer need to work anything out. Richter demands that we engage in the process of mediation, that we forgo knowing, which in any case is an illusion.

I propose that the Jackie-we-think-we-know is not the subject of this painting; rather, that this is a painting about appearance in which Jackie Kennedy represents the iconic subject of our gaze – someone we are sure we know as she is so incomparably familiar. Richter takes Jackie-as-icon and uses her to symbolize what we don't (can't) know, that is, the lack.

This lack is inevitable: there cannot be an imposition of one person’s viewpoint upon another. That would be tantamount to “violence”, says Richter[12] who refuses to impose his own ideas on viewers of his art. Lacan shares this perception of violence as the imposition of one person’s ideas and interpretations upon another: “When the function of speech has become so firmly inclined in the direction of the other that it is no longer even mediation, but only implicit violence…”[13] then the function of speech in the analytic experience is altogether questionable. The Lacanian analyst will find a way of bypassing the conventional function of speech and interrupting the mundane discourse of the analysand.

Portrait and the Gaze

I don’t think the painter need either see or know his sitter. A portrait must not express anything of the sitter’s ‘soul’, essence or character. Nor must the painter ‘see’ the sitter in any specific, personal way”[14].

This statement about portraiture by Richter recalls the Lacanian concept of desire as embodied in the gaze of the other. A child may seek to catch the object of his mother’s gaze which appears to him imbued with her desire, but he is never able to capture it; he can never know the object of the [m]other’s desire. In Lacanian terms, desire simply is; Bruce Fink calls it the state of “pure desirousness”[15]. It has no object and cannot be fathomed. I propose that Richter’s paintings embody the same notion and that he tries to both capture and negate the unfathomable gaze.

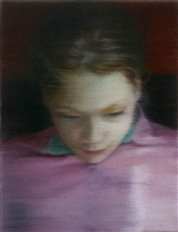

Fig 9: Ella, 2007

Fig 9: Ella, 2007

The painting of Ella (Richter's daughter) is a reflection of the averted gaze. Here Richter gives us an impression of Ella, but no more than that. This is a painting which is purely about appearance. In Ella we have an impression of her which, as our eye moves down the painting from top to bottom, seems to fade away – an impression of someone we might see on the street whose appearance we catch and then lose and quickly forget. The painting questions the function of portraiture in the media age. Although Richter's portraits contain many of the qualities attributed to the genre by art history, Richter manages to completely undermine our expectations of portraiture. Working as a man very much of his time, Richter turns the portrait into a representation of representations wherein the painterly techniques he employs, such as blurring, are just as important as the elements which permit us to “recognize” the person we are viewing. We must regard differently what we think we know. The all-too-familiar concept of “portrait” which we take completely for granted - ever more so since the advent of the digital camera and the ease with which a portrait is captured – must now be considered anew, with different elements. As technological innovation impacts profoundly on the media, and we are offered myriad representations of people and events in real time, we have to look for new ways of processing what it is we see. This too is embedded in the message Richter offers us about appearance.

In the same vein, Lacan moves the original concept of (Freudian) psychoanalysis into the background. He has re-formulated it so that it has a new primary function. Psychoanalysis is no longer about putting ‘I’ where ‘it’ was (wo Es war, soll Ich werden) through the process of free association, transference and counter-transferential understanding and intellectual interpretations. It is no longer the talking cure in the presence of an all-knowing analyst. In Lacan’s re-formulated psychoanalysis there is no omniscient analyst, no Other who sees the truth. The Lacanian analyst can only ask questions of the analysand which will help him to take responsibility for himself and in this way put I where previously ‘it’ prevailed.

Bruce Fink’s reading of Lacan proposes that the way in which a man looks at a woman may arouse the desire of the woman; or the way in which a woman speaks may arouse the desire of a man. It is neither the gazing man, nor the speaking woman – or their characteristics and qualities – which arouse desire, but the unsymbolisable ways in which they look and speak. In Fink’s own words:

“…the Other’s desire as manifested in the voice and in the gaze, both of which are unspecularizable: you cannot see them per se, they have no mirror images… They belong to the register of the ‘real’… They are nevertheless closely related to the subject’s most crucial experiences of pleasure and pain, excitement and disappointment, thrill and horror”[16].

It is at this point where we may see Lacan and Richter as being closest in terms of their expression of the ‘real’, and they arrive at it through a mutual mistrust of the perceived world: the visual for Richter is analogous to the spoken for Lacan. Just as Lacan mistrusts what he hears spoken in the ‘symbolic’ register, so Richter was innately suspicious of any definition of “reality” contained in paintings. He understood the reality that we see as being:

“...mediated through the lens apparatus of the eye, and corrected in accordance with past experience... all our reference points, everything we talk about the way we act – it’s all clichés”[17].

Similarly, Lacan explores optics in his Seminar, “The Line and the Light”:

“The essence of the relation between appearance and being... is not in the straight line, but in the point of light – the point of irradiation, the play of light, fire, the source from which reflections pour forth. Light may travel in a straight line, but it is refracted, diffused, it floods, it fills”[18].

As a result:

“In this matter of the visible, everything is a trap, and in a strange way... entrelacs (interlacing, intertwining)”[19].

Thus for Richter, his paintings do not represent an idea; they themselves are the idea in visual or pictorial form[20]. There is no difference for Richter between abstraction and realism and this is perhaps best represented in the Grey series, which gave him an opportunity to reiterate John Cage’s words: “I have nothing to say and I am saying it”[21]. Or as Richter states in a letter to the art critic, Benjamin Buchloh:

“...I can communicate nothing... there is nothing to communicate... painting can never be communication... [no] trick whatever is going to make the absent message emerge of its own accord... I look for the object and the picture: not for painting or the picture of painting... I want to picture to myself what is going on now...”[22].

This, in turn, recalls Lacan’s interpretation of de Saussure’s structural linguistics: there are only signifiers and the signified; there are no meanings that stand alone outside of the random chain of signification. In Lacanian terms, no matter what we articulate in the ‘symbolic’ order, the object of desire is but a signifier in a chain of endless signifiers.

Richter was looking for a painterly way to transcend understanding – which, in Lacanian terms, would mean understanding in the ‘symbolic’ order - and achieve a level of incomprehensibility. Richter gives his definition of incomprehensible:

“...[incomprehensibility] partly means ‘not transitory’: ie. essential. And it partly means an analogy for something that, by definition, transcends our understanding, but which our understanding allows us to postulate”[23].

Some essential aspect of ourselves or our lives which was incomprehensible and therefore unsymbolised and unfathomable, is now re-presented to us in a form which evokes questions which, in turn, may lead to symbolisation and understanding. The Grey paintings are a good example. They resist casual intellectual description; they are at first glance purposeless, then – at least for this

Fig 10: Grey, 1970 Fig 11: Grey, 1970

Fig 12:Inpainting (Grey), 1972 Fig 13: Grey, 1973

viewer – they evoke the purposelessness of life that we sometimes feel, or the void that we fall into when life delivers pain, tragedy and meaninglessness. There is no innate compassion, no god to take our troubles to, in Richter’s world. Rather, like the analytic session, the Grey paintings offer a surface which reflects the viewer back to him or herself.

Further, when confronted with an abstract painting, we look for a word in the title, or some visual sign to give us a clue as to what it is. This quest for the familiar obviates the need to recognise the nothingness or void of the ‘real’ which is embodied in the utterly unknown and which is equatable to death. Richter himself says:

“The abstract works are my presence, my reality, my problems, my difficulties and contradictions. They are very topical for me”[24].

In the Grey series, as Richter struggles with his own reality, problems, difficulties and contradictions, the viewers are drawn into the “presence” that Richter describes in paint and there lies the opportunity to encounter the ‘real’. The viewer can avert her eyes, or look for a way to speak what she feels and articulate what the otherness or strangeness means to her.

As noted above, Lacan sees a trap in everything that we see. In Richter's art we find visual representations of those traps, perhaps most obviously in the mirror-paintings and ready-mades.

Fig 14: Grey mirror, 1992 Fig 15: Mirror, blood red, 1991

In the 1980s Richter experimented with the mirror, painting pictures of red, grey and clear mirrors, and making colour-coated ‘ready-mades’. Stefan Gronert suggests these be regarded as portraits as they faithfully reproduce the image of the viewer, and “reveal the psychological meaninglessness of the mere surface”[25]. In this respect we see Richter and Lacan at the closest point in their thinking and their treatment of the visual; Richter’s painted mirrors can be understood as directly representing Lacan’s concept of the mirror-image: the viewer looks at herself in the painting and re-recognizes (mis-recognises again) herself as the image she has come to know as ‘I’. But the mirror is empty; it is painted grey (no-thing). The viewer simultaneously sees nothing and sees herself; she is confronted therefore with a specular re-presentation of the lack of being (manque-à-être) that, in Lacanian terms, she is.

Alternatively, the viewer may confront Richter’s mirrors painted in red and recognize the colour of blood that runs through the veins of the ‘real’, encountering a negation of the image of specular unity, or the smooth superficially acceptable ego he calls “me”. In this case the viewer is offered a glimpse of the abject - that part (blood) which is normally contained within; or that which resides in the unconscious. But he is not offered any insight into the internal world of “me”; there are no immutable truths that the artist (or the mirror) can convey.

In addition, as person and mirrored image stand in mutual confrontation they gaze at one another in an endless questioning. This recalls Lacan’s dialectic of lack between the eye and the gaze: the mirror becomes the screen, or site of mediation where the subject meets both herself and the gaze.

The Betty portraits below draw our attention to how we look at what we see and draw us to follow their gaze, recalling the iconic portrait of the Mona Lisa.

Fig 16: Betty, 1977 Fig 17: Betty, 1977

Fig 18: Betty, 1988

Fig 18: Betty, 1988

In Fig. 16, Richter’s blurring technique works to negate any recognition by making the subject so indistinct. But a Lacanian reading of this technique recalls Freud’s concept of negation and we understand that this blurring-as-negation is actually an affirmation – this is a kind of Mona Lisa, but not the kind we have come to expect. This one undercuts our expectations, initially by virtue of the blurring; so we have to ask, what kind of portrait is this?

If Mona Lisa was an icon of the mysterious to her 16th century viewers, as represented by her apparently all-seeing eyes and strange smile, perhaps this Betty is an icon of something mysterious located in the 20th century. How hard it is to represent mystery in our age when even the most hidden and remote elements are now visible and accessible: genes, atoms, microbes and pictures from Mars! What is mysterious to us today, in the context of this study, is desire; more specifically the Lacanian desire of the other embodied in the gaze. One way Richter finds to represent the mysterious gaze of his subject in these Betty pictures is by blurring the portrait or turning it on its side, as he does here with Betty. He literally over-turns the original concept of the portrait and we have to ask why. In this context, it is the father who has painted his child, so we might also include the possibility that we are also looking at the father's desire to fathom the desire of his daughter. In 1977 he paints her as mysterious, beautiful and desiring. The 1977 portrait (Fig 17) stares up at us, positioned rather awkwardly on her back, yet looking up at the viewer with a gaze which is completely calm and in repose – as relaxed and confident as the Betty who turns away. She has nothing to say and we know nothing about her. We are left as viewers with only the surface, but also perhaps the words of Lacan which approach quietly as we gaze at this picture: “You never look at me from the place at which I see you”[26] - words which might be spoken by the father who gazes at his child gazing at him, and which underscore not only the lack but also the very human desire to be recognized as loving father, as independent child – the viewer cannot possibly know the desires encapsulated in the gazes to which we are witness.

The 1988 Betty (Fig 18), painted a decade later, is even more pointedly representative of the concept of lack. She looks at a point behind her, out of the viewer’s sight, which “guides the viewer’s gaze into the infinite distance”[27] - somewhere which pulls her into an awkward pose – an anti-pose; she is an anti-portrait and characteristically Richterian in the sense that this portrait both fulfills and undermines our expectations of the genre. In Lacanian terms, there is the lack of a face and therefore of recognition, of course, but also the lack of any ability to fathom the gaze, ie. the desire of the Betty of this painting. Indeed here, even the gaze itself is lacking and we are left with what I can only describe as a tantalising view of Betty, which underscores desire and lack.

Concluding note

I have interpreted these samples of Richter’s work as an effort to paint - or symbolize in painterly terms - the gaze as cause of desire. Richter’s techniques of blurring and fading remind us of the impossibility of specularising the gaze as cause of desire. But Richter’s works also offer a graphic representation of Lacan’s notion of the screen: his paintings both screen us from the trauma because they are only representations, and simultaneously act as a screen upon which we face the trauma because in our human-ness we are drawn to look.

Bruce Fink comments that the gaze of the other has no mirror image[28], and so takes us into the ‘real’, thus setting off the dynamic of repetition as the Thing-like quality of the gaze resists symbolization. This resistance is reflected in the analytical process: the benefits of the “talking cure” emerge from assimilating the traumatic experience into language. In analytical terms, only an experience which is spoken – translated into the symbolic – can be drained of its traumatic content. Once we hit the real (as Fink puts it) we can articulate desire. When words fail us, perhaps art or photography can give us the tools we need to describe feelings, to locate and articulate the unspeakable, and to situate ‘I’ where ‘it’ went before.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Barthes R. (1984), Camera Lucida, London: Flamingo.

Becker J. (1989), Hitler’s Children: The Story of the Baader-Meinhof Terrorist Gang, 3rd edition, London: Pickwick Books.

Elger D. & Hans U. Obrist (eds), (2009), Gerhard Richter Text, London: Thames & Hudson.

Fink B. (1995), The Lacanian Subject, Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Freud S. (1905), “Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality”, SE VII.

Freud S. (1925), “Negation”, International Journal of Psycho-Analysis, 6: 367-371.

Freud S. (1960), The Ego and the Id, (trans. Joan Riviere). New York: W.W. Norton & Co Inc.

Freud S. (1965a), The Psychopathology of Everyday Life, (trans. Alan Tyson). New York: W.W. Norton & Co.

Freud S. (1965b), The Interpretation of Dreams, New York: Avon Books.

Furnari R. (2002), Screen (2), http://csmt.uchicago.edu/glossary2004/screen2.htm, [accessed 29.6.10].

Gronert S. and H. Butin (2006), in H. Cantz (ed), Gerhard Richter Portraits, Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz Verlag.

Homer S. (2005), Jacques Lacan, London: Routledge.

Lacan J. (2006), Ecrits, (trans. Bruce Fink). New York & London: W.W. Norton & Co.

McGonagill D. (2006), Warburg, Sebald, Richter: Toward a Visual Memory Archive, (doctoral thesis), Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press.

Miller J.A. (ed), (1981), The Seminar of Jacques Lacan, Book XI. The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis, (trans. Alan Sheridan). New York: W.W. Norton & Co.

Miller J.A. (ed), (1988a), The Seminar of Jacques Lacan, Book I. Freud’s Papers on Technique: 1953-1954, (trans. Sylvana Tomaselli). New York: W.W. Norton & Co.

Miller J.A. (ed), (1988b), The Seminar of Jacques Lacan, Book II. The Ego in Freud’s Theory and in the Technique of Psychoanalysis: 1954-1955, (trans. Sylvana Tomaselli). New York: W.W. Norton & Co.

Miller J.A. (ed), (1998), The Seminar of Jacques Lacan, Book XX. On Feminine Sexuality: The Limits of Love & Knowledge, 1972-1973, (trans. Bruce Fink). New York: W.W. Norton & Co.

Roudinesco E. (1999), Jacques Lacan, United Kingdom: Polity Press.

Storr A. (2002), Gerhard Richter: Forty Years of Painting, New York: Museum of Modern Art.

[1] Roudinesco, p.435

[2] Ibid, p.375

[3] http://www.npg.org.uk:8080/richter/exhib.htm [accessed 28.6.2010]

[4] Miller (1988b), p.192

[5] Fink, p.24

[6] Ibid.

[7] See Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida,

[8] Miller, 1981, p.93

[9] Storr, .289

[10] Fink, p.95

[11] Miller (1981), p.97

[12] Elger & Obrist, p.32

[13] Miller (1988a), p.51

[14] G. Boehm, in Cantz (ed), p.209

[15] Fink, p.91

[16] Ibid, p.92

[17] Elger & Obrist, p.65

[18] Miller (1981), p.94

[19] Ibid, p.93

[20] Elger & Obrist, p.70

[21] Ibid, p.94

[22] Ibid, p.93

[23] Ibid, p.120

[24] Ibid, p.146

[25] S. Gronert in Cantz (ed), pp.63-64

[26] Miller (1981), p.103

[27] S. Gronert in Cantz (ed), p.57

[28] Fink, p.92

Received: May 18, 2011, Published: July 9, 2011. Copyright © 2011 Lesley Marks