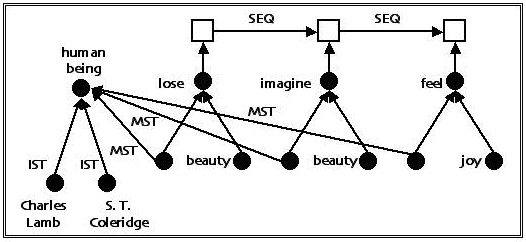

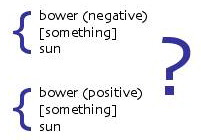

By recasting Vygotsky’s account of language acquisition in neural terms we see that language itself functions as a transitional object in Winnicott’s sense. This allows us to extend the Schwartz-Holland account of literature as existing in Winnicottian potential space and provides a context in which to analyze Coleridge’s "This Lime-Three Bower." The attachment relationship (between Caretaker and Child) provides the poem’s foundation. The poet plays the Child role with respect to Nature and the Caretaker role with respect to his friends. The friends, Charles in particular, play the mediating the role of transitional object in the first movement while Nature becomes a mediator between one person and another in the second movement. The first movement starts with the poet being differentiated and estranged from Nature and concludes in an almost delusional fusion of poet, friends, and Nature. The second movement starts with the poet secure in Nature’s presence and moves to an adult differentiation between poet, friends, and Nature.

The supposedly separate realms of the subjective and the objective are actually only poles of attention. The dualism of observer and environment is unnecessary. The information for the perception of "here" is of the same kind as the information for the perception of "there," and a continuous layout of surfaces extends from one to the other. . . . Self-perception and environment perception go together.

-J. J. Gibson, The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception

The place where cultural experience is located is in the potential space between the individual and the environment (originally the object). That same can be said of playing. Cultural experience begins with creative living first manifested in play.

-D. W. Winnicott, Playing and Reality

In the working model of the world that anyone builds, a key feature is his notion of who his attachment figures are, where they may be found, and how they may be expected to respond.

-John Bowlby, Separation: Anxiety and Anger

Language and Love

In the summer of 1973 Dœdalus published a special issue on "Language as a Human Problem." Looking back, I would imagine that I recognized only three of the names on the cover - Morton Bloomfield, Dell Hymes, and Eric Lenneberg, whose now-classic Biological Foundations of Language I had studied with considerable interest and care - but I purchased the issue because the topic interested me. Judging from my marginal notations I read twelve of the seventeen articles, including Lenneberg’s on "The Neurology of Language," but not Edward Keenan on "Logic and Language." I do not recall just why I passed over that one, but I suspect it was because I had taken a rigorous course in symbolic logic as an undergraduate and thus had spent many hours translating the meanings of ordinary and rather simple English sentences into logical formulae. I did not find that terribly difficult, but it wasn’t very illuminating either. However meaning worked, it seemed to me it surely did not work like that.

Apparently I read Paul Kiparsky’s "The Role of Linguistics in a Theory of Poetry," but I do not remember the central points of his argument. Certainly I would have read an article with such a title, for I was then preparing to enter graduate school to write a dissertation on language and poetry. I suppose if I do not remember Kiparsky’s article it is because I wanted to know how language means, and he had little to say about that, nor did linguistics in general have much to say on that subject. There was something called generative semantics, but it looked more like syntax than semantics to me, and it was a little too close to formal logic for my comfort.

The article that I ended up reading with the greatest care and interest was written by a scholar I’d never heard of, David G. Hays: "Language and Interpersonal Relationships." The first sentence took the form of a question: "How does language engender love?" I cannot say that, at this time, I recall the central points of Hays’s article any more than I do those of Kiparsky’s. That is because I so studied his article that I internalized his ideas and so can longer distinguish them as specific objects of thought.

Hays’s subject would have interested Coleridge, who wrote a series of poems in which he explored his love for a small circle of intimates. These poems, generally known as the Conversation Poems, all take the form of an address from the poet to a familiar companion, variously Sara Fricker, David Hartley Coleridge (Coleridge’s infant son), Charles Lamb, the Wordsworths, or Sarah Hutchinson. "This Lime-Tree Bower My Prison" is one of these and first appeared in a letter to Robert Southey written on 17 July 1797. Coleridge tells Southey how he came to write that text (in Wheeler 1981, p. 123):

Charles Lamb has been with me for a week - he left me Friday morning. - / The second day after Wordsworth came to me, dear Sara accidentally emptied a skillet of boiling milk on my foot, which confined me during the whole time of C. Lamb’s stay & still prevents me from all walks longer than a furlong. - While Wordsworth, his Sister, & C. Lamb were out one evening;/sitting in the arbour of T. Poole’s garden, which communicates with mine, I wrote these lines, with which I am pleased?

The poem then follows directly. A moderately revised version was published in 1800, "Addressed to Charles Lamb, of the India House, London."

On Coleridge’s account then, the poem has its origins in a sense of loss, Coleridge is confined to quarters unable to go out rambling over hill and dale with his friends. Thus this poem at least seems to invert the familiar Wordsworthean formula of "emotion recollected in tranquility." The first text seems to have been an attempt to bring a state of tranquility out of the anxiety and sadness of unwanted isolation. That is, Coleridge is using language as a means, if not of engendering love, at least of restoring himself to a sense of being loved by others and of having the power actively to love them.

It is in those terms that I will conduct my analysis, which proceeds by stages, alternating theoretical and methodological issues with practical analysis of Coleridge’s poem. As a courtesy to devotees of the so-called Cognitive Turn, I feel honor-bound to disclose my intention to argue for the continuing relevance of psychoanalytic thought. I agree with Alan Richardson and Francis Steen (2003, p. 156) that we have "a striking opportunity to learn from and contribute to an emerging understanding of the human mind" based on these new lines of inquiry. I can even agree with them when they assert that "cognitive and neuro-scientific research and speculation do strike us as far more interesting than, say, psychoanalysis or pre-Chomskian linguistics." The fact that I find these newer psychologies more interesting does not, however, mean that I have dismissed psychoanalysis from my working conceptual tool kit.

I have, on the contrary, found psychoanalytic ideas indispensable in thinking about literature (e.g. Benzon 1998, 2003) but feel that psychoanalysis needs to be reconstructed in new terms, not discarded. Thus, while critical pieces of my conceptual apparatus in this essay derive from the newer psychologies, the general strategy of my analysis derives from psychoanalysis. Beyond its value as an analysis of "This Lime-Tree Bower My Prison," I regard this essay as an example of how literary analysts can contribute to the reconstruction of psychoanalytic thinking by using intellectual tools that were unavailable when psychoanalysis was first conceived.

Affective Technology

When Coleridge published "This Lime-Tree Bower My Prison" (henceforth LTB) he presented it with a short preface:

In the June of 1797 some long-expected friends paid a visit to the author’s cottage; and on the morning of their arrival, he met with an accident, which disabled him from walking during the whole time of their stay. One evening, when they had left him for a few hours, he composed the following lines in the garden-bower.

In a general way, it tells much the same story he’d told Robert Southey three years before. As Kathleen Wheeler has pointed out (1981, p. 146) there are discrepancies between the two versions. For example, the July visit of the 1797 letter has been displaced to June in the 1800 preface and the second-day accident of 1797 has been mis-placed to the first day in 1800. But the central point remains the same: Coleridge was separated from his friends by an accident. They were able to go walking about in Nature while Coleridge was not. He wrote the poem while his friends were out and about and he was confined to the garden.

But why did he write the preface at all - Wheeler suggests that "the most fundamental function of the preface is to establish some relation between the poem as art and the world of reality" (146). I agree with that, though I find the implications she draws from that to be a bit over complex. Coleridge was simply telling us: That’s how it happened, what it says in the poem. My friends deserted me; I was feeling alone; I started thinking about what they might be seeing, started composing a poem on that topic, and, all of a sudden, I was feeling better.

The poem itself says nothing about poetry; it simply reports the poet’s thoughts and feelings of an evening. In contrast, the preface does talk about poetry, or rather, about the poem to which it is affixed. By saying that Coleridge himself, like the person who speaks the poem, was alone one evening while his friends went for a walk, the preface indicates to us that the act of writing the poem played some role in the process that brought about a change in his mood. In brief, Coleridge is telling as that poetry is affective technology, a mind-altering activity.

There is nothing strange in that, at least I do not myself find it strange. I would assume that notion is comfortable and familiar to professional students of literature, but I do not really know, because the practice of critical "reading" tends to focus on meaning, not feeling. We may talk about what characters in novels, plays, and poems feel; but we tend not to talk about what readers or play-goers feel, neither in specific (this or that person) or in general terms.

I do not see any way radically to change that situation. Though I will shortly offer a minor bit of personal revelation, I have no interest in calling for a more confessional criticism. Some people can do that well, but I do not think that such writing is a useful starting point for an objective understanding of the mechanisms that underlie this affective technology, though it may provide raw data for such study. I do think that we should pay more attention to just how people actively use literature to change their moods, much like musicologists Tia DeNora, Music in Everyday Life, Charlie Keil, My Music (Crafts, Cavicchi and Keil 1993), and others (cf. Juslin and Sloboda 2001) have been doing. But I am not going to argue for that kind of work in this essay, as it isn’t specific enough for my present intellectual purposes. I am more interested in recent brain-imaging studies that reveal deep brain activity in response to music, Anne Blood’s work for example (1999, 2001, 2003), or Semir Zeki’s work on romantic love (Bartels and Zeki 2000) and beauty (Kawabata and Zeki 2004).

The conceptual distance between any of the various conventional vocabularies of literary analysis and that of brain imaging is, alas, more of a canyon than a gap and I do not propose to close it. But I can toss a few cables across the canyon in hope that others will find them useful in constructing a bridge. Thus I will use John Bowlby’s work on attachment to conceptualize the relationship between mother and infant. Bowlby was trained as a psychoanalyst, but came to reconstruct the dynamics of that relationship in terms of behavioral biology and informatics. I will then propose simple neural relationships in which to think about Winnicott’s work on transitional objects and elaborate on the model by drawing on L. S. Vygotsky’s account of language learning. That will lead us directly to Norman Holland’s recent work on the neuro-psychoanalytic foundations of literary experience.

Loss and Restoration

When I was young my parents would punish me by sending me to my room. Not only was I thus unable to continue doing whatever it was that I had been doing, but I was also separated from the world in general and, of course, separated from my parents in particular. While confined to my room I would feel aggrieved and brood for a bit and sooner or later imagine a scenario in which I had died somehow. I would continue the story by imagining my parents grieving for me, and saying how they had wronged me, but it’s too late now because I’m dead. By then I would start feeling better.

This, of course, is a form of play, though it is not the sort of thing that typically comes to mind when we think of childhood play. But play it is, for it required me to imagine myself in a role quite different from my actual situation. It also required that I imagine a situation in which my parents were as bereft as I felt, thereby making me superior to them.

I have no idea how common this particular mood-altering play scenario is, but something like it seems to have informed Chapters 13 through 15 of Mark Twain’s Tom Sawyer. While the incidents in those chapters may have been based on Twain’s childhood experience, those chapters are themselves works of fiction. We can read them in an hour or so, but they depict fictional events that transpired over a course of days.

As Chapter 13 opens, Tom is feeling aggrieved. His aunt had recently punished him for a prank he had played on the family cat and Becky Thatcher was ignoring his romantic overtures.

Tom’s mind was made up now. He was gloomy and desperate. He was a forsaken, friendless boy, he said; nobody loved him; when they found out what they had driven him to, perhaps they would be sorry; he had tried to do right and get along, but they would not let him; since nothing would do them but to be rid of him, let it be so; and let them blame him for the consequences -- why shouldn’t they? What right had the friendless to complain? Yes, they had forced him to it at last: he would lead a life of crime.

Tom encounters his friend Joe Harper, who is of a similar mind, and they join up with Huck Finn and run away to Jackson’s Island, where they intend to live a fine life as pirates.

Late in their second day they hear canon shot over the water. Tom concludes that the townsfolk suspected the boys had drowned and so were trying to bring their bodies to the surface. That night - we are now in Chapter 15 - Tom slips back to town and sneaks into his house. There he listens to his Aunt Polly and to Joe’s mother commiserating over their loss, affirming that, though a bit devilish, their boys were good at heart. These words had a powerful effect on Tom:

Tom was snuffling, now, himself - and more in pity of himself than anybody else. He could hear Mary crying, and putting in a kindly word for him from time to time. He began to have a nobler opinion of himself than ever before. Still, he was sufficiently touched by his aunt’s grief to long to rush out from under the bed and overwhelm her with joy - and the theatrical gorgeousness of the thing appealed strongly to his nature, too, but he resisted and lay still.

Tom then returned to the island in time for breakfast and "recounted (and adorned) his adventures. They were a vain and boastful company of heroes when the tale was done."

Though I do not recall the details of any of the childhood fantasies I employed to restore my sense of well-being, I rather suspect that Twain’s three chapters are more richly realized than anything I managed to conjure up. The most interesting aspect of Twain’s story is that the boys ran away to become pirates. That is, within the means available to them, they did their best to become free and autonomous actors rather than being bound to adults in the role of a child. It was from within that bit of adventuresome pretense that Tom overheard the heart-warming conversation. Though sorely tempted, he did not immediately break from his pretended autonomy. Rather he returned to the island and thus afforded Twain the pleasure of extending this theme through four more chapters worth of variations.

Let us now return to LTB. As I mentioned in the introduction, we know from Coleridge’s own hand that the first text of the poem was occasioned by an incident which prevented him from going on a nature walk with his friends, Dorothy and William Wordsworth and Charles Lamb. So it is possible that the writing of the poem was occasioned by a bout of melancholy and that, by the time a text had been drafted, the melancholy was gone. I take Coleridge’s account of the poem’s origins, however, as nothing more than a clue to its supporting affective dynamic. Yet it is a clue that was important enough to Coleridge that, when he published the poem, he provided it with a preface indicating roughly, though not exactly, what he had said in the letter to Southey.

We should, nonetheless, remind ourselves to honor the distinction between that real occasion and the poem itself regardless of how well the events in the moment mimic the real events of the evening. The events of the evening took place over some hours, but one can read the poem itself in a few minutes. And you do not need to know anything about Coleridge’s life or the topography of the Lake District to understand and appreciate the poem.

With these various experiences in mind, the real and fictional, I want to turn to the work of John Bowlby (1969, 1973, 1980; Parkes and Hinde 1982), who has revised traditional psychoanalytic understanding of the psychology of attachment, loss and separation. Trained as a psychoanalyst, Bowlby came to doubt the classical psychoanalytic belief that the child’s attachment to her mother was rooted in the mother’s provision of nutrition. He came to believe, instead, that it was the mother’s caring presence itself that was significant to the infant and undertook an extensive cross-disciplinary conceptual program to argue his case. One of Bowlby’s signal moves was to ground his study of human attachment in the ethological literature about attachment among animals, including imprinting in birds. To this I would add more recent neurobiological work that has identified many of the neural circuits mediating infant-parent bonding (e.g. Panksepp 1998, Konner 2004). This behavior has a long phylogenetic history and is mediated by specific neural circuits.

It is those circuits, I am suggesting, that are active in the various real and fictional cases of loss or separation we have been considering. In the case of the real events- my childhood maneuver, Coleridge’s experience one evening in 1797 - the circuits are those in my brain and in Coleridge’s. In the case of the fictional events - Tom Sawyer’s fictional activity, and the events in LTB - the circuits are those in the brains of those who read those fictions. In these latter cases the readers may be reading those texts to sooth some sense of real loss in their lives, but not necessarily so. They may just be reading for pleasure - or to satisfy a course requirement.

These situations are sufficiently different that I think they require different accounts, but I have no intention of attempting that here. My interest is in one case, that of the brain of someone reading LTB. But I would first like to make some more general remarks.

Let us remind ourselves that attachment is a relationship and, as such, involves two parties, the infant or Child and the Caretaker - terms I will use when talking about these roles. Discussions of attachment tend to focus on the infant, on her need for attachment, her strategies of maintaining it, her response to loss, and so forth. But the infant’s activities would be fruitless if the Caretaker were not highly motivated, not only to respond to the infant’s actions, but to anticipate the infant’s needs and actively to arrange the world for the infant’s benefit. While the relationship is very intense for both Caretaker and Child, they play very different roles in that relationship.

This leads to a suggestion about the mechanism of the particular psychological strategy I have been examining: at the point where the child is imagining his parents in grief over the child’s death, that child has, in his imagination, assumed the Caretaker role in the attachment relation. The child can thus reinterpret his own sense of loss as empathy with or response to his parent’s grief over the child’s imaginary death. Further, as the child imaginatively enacts the Caretaker role he can project the Child role onto his parents. Thus the child can master his own sense of separation and loss by employing his identification with his parents to engineer an imaginative transformation of that loss. That, more or less, is what I suspect I was doing as a child.

And I propose that that is what Mark Twain was depicting in Tom Sawyer. That is why I called attention to the fact that Tom and Joe ran off to be pirates and thus had, at least in their own minds, ceased to be children. They had become autonomous adults of a particularly adventuresome kind, living at the fringes of civilization. It is from that point of view that Tom observed the conversation between Aunt Polly and Mrs. Harper and it is from that point of view that he felt an impulse to reveal himself to his Aunt and thus relieve her grief and anxiety. Twain tells us, however, that that impulse also came with a sense of "the theatrical gorgeousness of the thing." That has the smell of the child about it. But I regard that as further evidence of my point, that in a person mature enough to take at least some care for others it is easy, under the appropriate circumstances, to flip from one role to the other in the attachment interaction.

Just what is going on in the brain of someone reading Tom Sawyer is, of course, a different question. I have already argued (Benzon 2001) that we use the same neural circuits to understand fictional events that we use to understand and enact real events, but I don’t want to repeat those arguments here. The reader of Twain’s book thus has an opportunity to enact a certain strategy for mastering loss in a context that is completely safe, as the events are not real and so the readers' own welfare is not in jeopardy.

And so, I will be arguing, does the reader of LTB. We must be careful, however, in identifying just what it is that has been lost. Both the preface and the opening lines of the poem quite clearly state that his friends have left him alone. Once he has registered that fact, however, the first loss the poet complains about is that of "beauties and feelings." His friends may have left him, but it isn’t their presence that he misses, it is those beauties and feelings, by which he presumably means the things his friends will see on their walk. He misses the opportunity to go out in Nature; that is why the bower is a prison. Something then happens during the first two stanzas that transforms the poet’s mood so that, when he once again turns his attention on the bower at the beginning of the third stanza, he does so in delight. The setting that had seemed barren is now experienced as overflowing with life.

It would seem that, if I want to analyze this dynamic in terms of the attachment relationship, then I have to put the poet in the Child role and (Mother) Nature in the Caretaker role. It is Nature that is lost in the beginning, and it is Nature that is found later on. The process that leads from the first state to the second involves the poet’s imagining what his friends might be seeing on their walk; they thus mediate his re-attachment to Nature. This relationship then becomes inverted in the course of the third stanza so that at the very end, Nature mediates the poet’s relationship with one of his friends, Charles Lamb:

My gentle-hearted Charles! when the last rook

Beat its straight path across the dusky air

Homewards, I blest it! deeming its black wing

(Now a dim speck, now vanishing in light)

Had cross’d the mighty Orb’s dilated glory,

While thou stood’st gazing; or, when all was still,

Flew creeking o’er thy head, and had a charm

For thee, my gentle-hearted Charles, to whom

No sound is dissonant which tells of Life.

He blesses the rook, not for what it is, but for what it is to his gentle-hearted friend. This natural creature, and the sun that is its setting, is a link to his friend, just has his friend had been his link to nature earlier in the poem.

Thus we must augment Bowlby’s account of attachment with a theory of mediation in the attachment relationship. Fortunately D. W. Winnicott has provided us with such a theory.

Transitional Objects

Winnicott’s theory is about what he calls transitional phenomena. By way of introduction, he tells us (1971, p. 2) that he is interested in

the intermediate area of experience, between the thumb and the teddy bear, between the oral eroticism and the true object-relationship, between primary creative activity and projection of what has already been introjected, between primary unawareness of indebtedness and the acknowledgement of indebtedness (’Say: "ta"’).

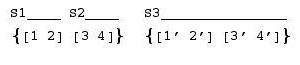

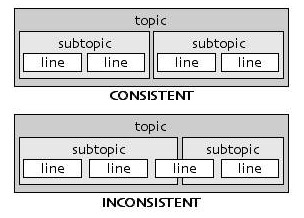

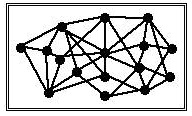

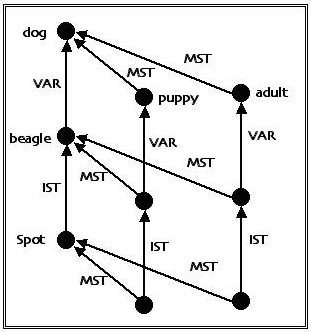

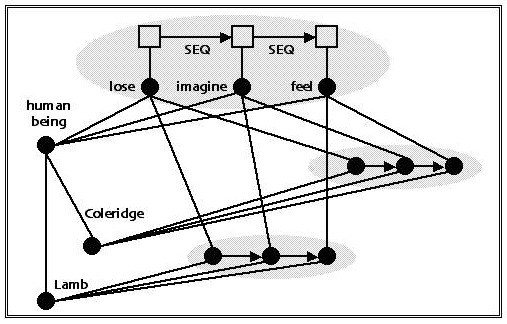

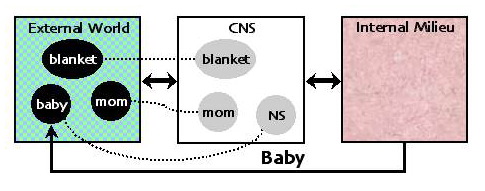

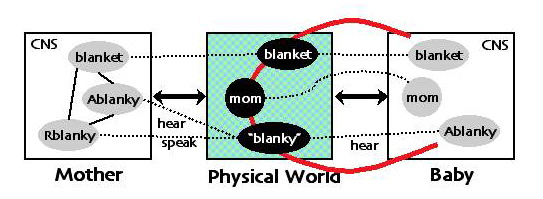

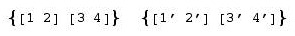

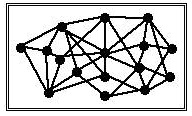

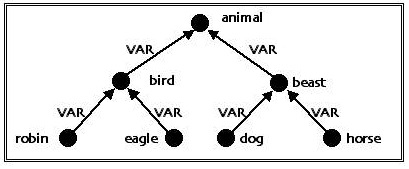

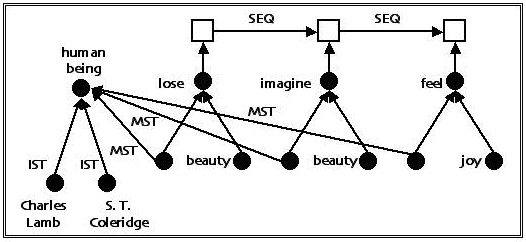

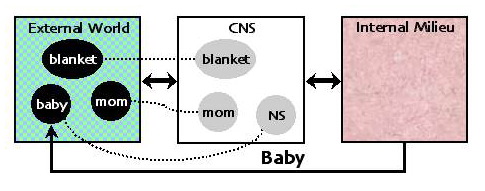

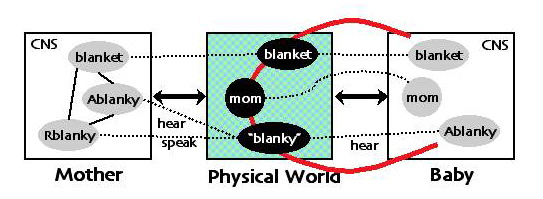

Prototypically, such objects include favorite blankets and toys. Winnicott is arguing that, while these objects are distinct from the infant, the infant does not quite treat them so. Consider the following diagram:

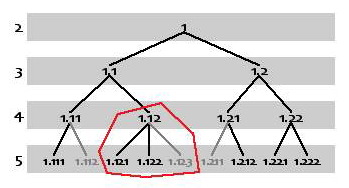

Figure 1: Transitional Object

The diagram depicts the fact that the central nervous system (CNS) regulates activity in two environments exterior to it, the interior milieu (represented to the right) and the external world (the box at the left). The CNS regulates activity in the inner world through the autonomic branch of the peripheral nervous system and through the hormones of the endocrine system. It regulates activity in the external world through control of the skeletal muscles and through sensory input from the eyes, ears, skin, tongue, and so forth. The double-headed arrows indicate these two-way functional relationships. We know, of course, that the CNS and the internal milieu belong to the same body, but the diagram does not depict that. The dotted lines, which I will describe later, indicate intentional relations between the infant and the world.

I have picked out three "chunks" of neural tissue for special consideration. One of them is the neural representation of some blanket, which is depicted there to the left in the external world. Another bit of tissue represents mom, the Caretaker figure, who is also there in the external world. Then we have the NS, Damasio’s (1994, 1999) neural self, which is a rather larger, more dispersed and considerably more diverse hunk of tissue (cf. Benzon 2000). The NS includes all the systems devoted to understanding and regulating the organism itself, as opposed to dealing with the external world. It thus includes the neural systems that regulate the internal milieu. It also contains the system that registers one’s personal history. But what is that link between the NS and this baby person in the external world?

As the diagram indicates, this nervous system is some infant’s nervous system. The baby indicated in the external world is the infant’s body as the infant sees it, touches it, smells it and so forth. For the infant’s body is out there in the external world just as mom and that blanket are. The arrow at the bottom of the diagram indicates that there is a direct relationship between the internal milieu and the body. If, for example, the heart rate increases and blood vessels in the skin open up, the infant’s body will be flushed, and she can see the color even as she feels and hears her heart pounding.

That blanket, of course, is the infant’s favorite blanket and serves her as a transitional object. Imagine the infant, mom, and blanket all playing together. Just how does the infant tell them apart? When you touch something, you have a sensation, but that sensation does not itself distinguish between the object and the skin. To make the distinction you have to move your skin over the object and correlate your touch sensations with both your motor effort and your sense of moving body parts. But the young infant lives in a world where her mother often moves her body for her, lifting her up and carrying her around, moving her limbs, and so forth. Sorting all of that into me and you is not simple and the addition of a soft blanket just makes it more challenging, because now it must be discriminated as well.

Finally, I note that the dotted lines indicate an intentional relationship between the nervous system and the external world. These are not relationships of physical causality; those are all summarized in the double-headed arrows. Rather, they reflect the meaning that the infant confers on those external things by virtue of her history and the current state of her needs and desires. I have the notions of intentionality and meaning from Walter Freeman's (1995, 1999) discussion of the nervous system, though both are consistent with at least some standard philosophical usage. The relationship between the neural self and baby is one of identification. In pathological states that identification may be broken but it may also be deliberately set aside for aesthetic or ritual purposes (cf. Benzon 2000). The relationship between the external and internal blanket and the internal and external mother is one of reference. Physical processes allow Jill to see, smell, and touch the blanket, but her intentional relationship to the blanket is given only in the internal dynamics of her nervous system. It is that relationship that is indicated by the dotted line.

It is in this intimate little world that an object can become a transitional object. The infant can control the object fairly well and so, to the infant it is not only mine, but it is me, almost as much as my hand is. It is familiar and comfortable and so much like mother. But it also resists the infant a bit and so is other. To the extent that these objects are within the infant’s grasp and power, the infant regards them as an extension of herself and assimilates them into what Winnicott calls the "personal pattern." He then goes on to note (p. 4):

Patterns set in infancy may persist into childhood, so that the original soft object continues to be absolutely necessary at bed-time of at time of loneliness or when a depressed mood threatens. In health, however, there is a gradual extension of range of interest, and eventually the extended range is maintained.

It is, of course, quite an extension to move from the toddler’s use of attachment objects to a fully adult poet’s use of a friend as a mediator between himself and Nature, and then to invert that relationship. The extension depends on three things. One of them is the analogy between the significance that the mother has to the infant and the significance the poet attributes to Nature. The second is the nature of language itself. The last is the fact that what happens in poetry transpires under a seal of disbelief, "that willing suspension of disbelief for the moment, which constitutes poetic faith," to use the formulation Coleridge himself used in Chapter XIV of his Biographia Literaria.

On the first issue, imagine that you are a licensed Affective Technologist and are being commissioned to design a system for the manufacture of Art as defined by the words quoted below. They are from the opening paragraph of Coleridge’s essay, "On Poesy or Art," that he published in 1818, two decades after having written LTB.

Now Art . . . is the mediatress between, and reconciler of, nature and man. It is, therefore, the power of humanizing nature, of infusing the thoughts and passions of man into every thing which is the object of contemplation; color, form, motion, and sound, are the elements which it combines, and it stamps them into unity in the mould of a moral idea.

The obvious thing to do, it seems to me, is to recruit the attachment relationship into service. It is the deepest and most fundamental relationship between a person and the world. For the infant, her mother is the world, and so Nature is to the poet. It is one thing to argue the case philosophically, but if you want to "make it so" - to borrow a phrase from Jean-Luc Piccard, Captain of the starship Enterprise - you can do it in a poem where the relationship between Child and Caretaker is used to bring life to the relationship between man and nature.

That gives us a way to think about the story Coleridge tells in LTB, but we still have to think about language and then about the virtual domain of poetry. Those topics are sufficiently complex that each deserves its own section.

Language, Feeling, and Culture

The critical insight belongs to Lev Semenovich (1962, Zivin 1979, Benzon 2000, 2001, pp. 151 ff.) the Russian developmental psychologist. He argued that, at the beginning, others use language to direct the child’s action - "come here" - and attention - "see the doggie." As the child gains control over her vocalization she begins using speech in that way herself. That is to say, she is assuming a function that had formerly belonged to her mother, and others as well. She is beginning to internalize that function. While the speech stream passes outside the child’s body and so is physically external, it is nonetheless performing an internal function, that of regulating attention and action. The internalization is complete when external speech is no longer necessary, though it will return when particular concentration is warranted or in times of stress.

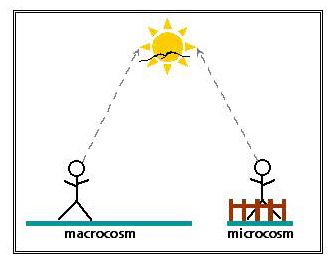

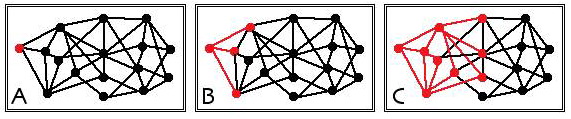

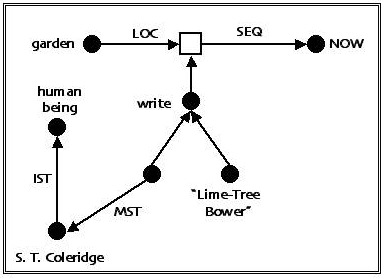

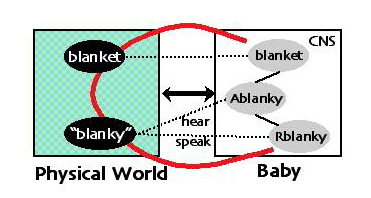

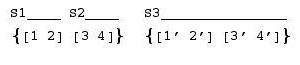

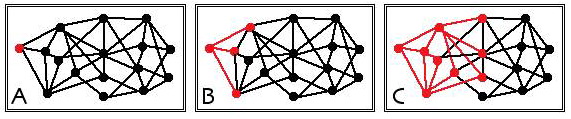

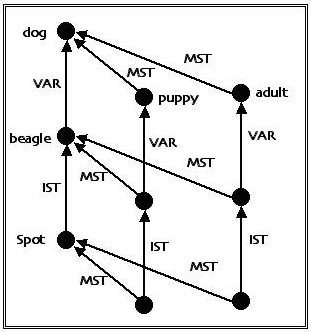

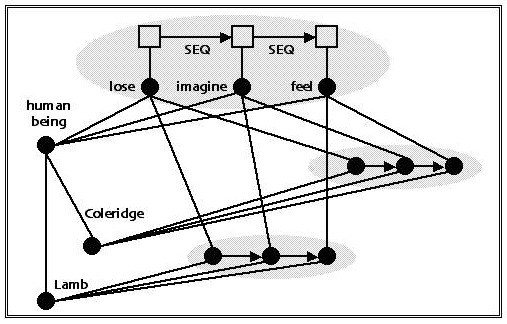

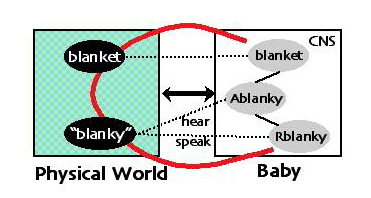

Consider Figure 2, where mother, infant, and blanket are playing at language:

Figure 2: Language in Potential Space

Mother’s nervous system is represented at the left while the infant’s is to the right. The physical world, which they hold in common, is depicted between them. Notice that the world contains both a blanket and the word "blanky," which represents the speech sounds used to indicate the blanket. Mother understands the connection between word and thing quite well; I have represented that by drawing a connection between the blanket node the blanky nodes, Ablanky and Rblanky. One blanky node is for the articulatory object (Rblanky), something executed by the motor system, while the other is for the auditory pattern (Ablanky), something one hears with the auditory system. Note that both Ablanky and Rblanky have an intentional relationship to the uttered sounds in the external world. [Following the same logic I should have one blanket node for the visual blanket, another one for the tactile blanket, one of the olfactory blanket and one for the gustatory blanket. But that seems a bit excessive for my present purposes.] In contrast, the relationship between the blanket and the word is not so secure for the infant, who is only listening to mother and only has the auditory representation, not the articulatory. Thus I have drawn no connection between the blank and Ablanky nodes in the infant’s brain, for none yet exists..

In this situation the infant’s sense of the connection between word and thing is critically dependent on her mother’s speech and intention as the infant reads them. That is to say, the infant is not only listening to mother’s speech and looking around in the world, but, as recent research shows, is actively monitoring mother’s angle of regard and facial expressions for clues about what she is attending to in the world as she is speaking (Bloom 2000, pp. 55 ff.; cf. Winnicott 1971 on the mirror role, pp. 111 ff.). While the infant has percepts of the sound thing, the link between those percepts is necessarily external to the infant (red line) as it includes the infant’s perception of mother and her activities. Mother is thus playing a role that is physically external but functionally internal to the infant’s mind-brain. Thus, in its formation, the link between word and thing is not merely one of the word "pointing" to the thing, but rather has implicit in it the social interaction of two human beings.

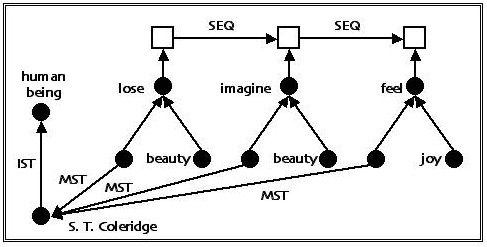

Figure 3 depicts a lone infant talking to herself while playing with her blanket:

Figure 3: Talking to Herself

Notice that there is no direct link between the articulatory blanky and, shall we say, the visual blanky (though it might be tactile as well) while there is such a link between the auditory and the visual blanky. The link between the articulatory and the auditory patterns is necessary for speech to occur at all. The infant practices this link though babbling. The link between the auditory pattern ("blanky") and the visual pattern is, in effect, something the infant learns while closely attending to mother’s expressions and actions as she talks. This linkage is something entirely out there, in the world. But there is no way for the infant to observe or sense a link between the articulatory and the visual patterns (at the ends of red line) except when the infant herself is speaking.

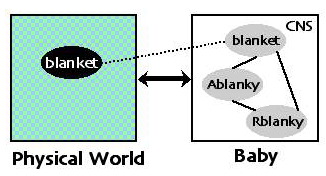

Thus while the infant rehearses the link between the auditory word and its meaning that she has observed so often when her mother was the speaker, she may also observe and solidify the link between the articulatory word and its meaning. In time, external speech is no longer necessary to evoke that link:

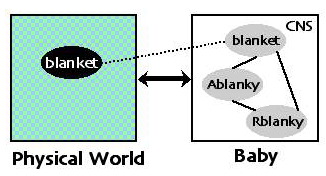

Figure 4: Inner Speech

The triangular linkage between the blanket schema, the word’s auditory, and its articulatory pattern is the familiar semiotic sign. The auditory-articulatory pair constitute the signifier while the visual-haptic-etc. blanket is the signified. The physical blanket out there in the world is, of course, the referent of the sign.

It is not at all clear whether language ever completely looses its status as a transitional phenomenon. The child who responds to taunts by chanting "sticks and stones may break my bones but names can never hurt me" does so precisely because names do hurt her, because she is unable to treat them as mere indices. Those nasty words exist in a space that is public in the sense that anyone can hear them but is private in that they directly affect the child’s feelings. Much language can be used more or less neutrally, more or less "out of range" of the affective life of speakers and hearers, and perhaps some very specialized language, such as the propositions and formulas of mathematics, can enter the private domain only under unusual circumstances, if at all. But what we call ordinary language has easy access to our inner life.

What is important in this account is that the process by which the sign has been created and stabilized in the child’s mind is, in effect, one of internalizing her mother. Because the mother spoke to and with the infant at one time, the infant is now able to produce inner speech for herself. In the next section I will argue that the "space" of literature comes into being when this sign function is once again "opened up." It is exactly because language originated in the public-private space between mother and child that we can, through appropriate cultural conventions, create the public-private space of literature.

Language is not the only phenomenon that exists ambiguously inside and outside. Recall from Figure 1 that the infant’s body is out there in the world as well. The physical indicators that signal the infant’s emotional and motivational state to others may also signal that state to the infant herself. Even as her heart is pounding away in excitement, she can feel the pounding in her chest, hear it in her ears, and sense the expression on her face that is so visible to others. This is the basis of the so-called James-Lange theory of emotion, which Damasio has reconstructed in his theory of the somatic sign (1994). What seems to be happening is this:

- Some subcortical centers generate output directed at heart rate, respiration, this that and the other, and muscle tone, posture, gesture, and facial expression.

- Various bodily activities change in ways that are visible to others, but also to the individual.

- Cortical brain centers detect these changes in various ways - you may hear your heart pounding, you can feel the pulse, see, smell, sense sweaty palms, and you can detect changes in muscle tone and posture though neural routes which are physically distinct from those in step 1.

So, we have one set of neural centers in step 1, a different set in step 3. And this particular communication between those centers, from 1 to 3, is external to the brain. There may also be connections between these centers that are internal to the brain, but we've got experimental evidence of various kinds indicating that some important information goes externally (Benzon 2001, pp. 40-42; Mandler 1975, pp. 131-33; Strongman 1973, pp. 76-78; Valins 1970).

Thus while emotional feelings and verbal meanings may be inside a person’s mind, the neuro-physical processes supporting these meanings and feelings have aspects that are public and external to the brain. In poetry the feelings and meanings are carried in one and the same verbal string through which activities in various brain-body centers are inter-related in a public space that can be shared with others. Thus we arrive at the passage from Winnicott (p. 100) that serves as one of the epigraphs to this essay:

The place where cultural experience is located is in the potential space between the individual and the environment (originally the object). That same can be said of playing. Cultural experience begins with creative living first manifested in play.

It is not so much that this potential space is between the individual and the environment (originally the attachment object) but that language and feeling and so play as well all involve information flows passing from one brain center to another by a route or routes that are outside the body. It is in this space that poetry is created and it is only when we are fully in this space that poetry is alive within us.1

Willing Suspension

In the formulation of Ernst Kris (1952), the creation and understanding of art involves a regression to earlier modes of experience, but a regression that is in service of the ego. In the more recent formulation of Norman Holland (2003), such regression involves an overall pattern of brain activity that is quite different from those obtaining when we engage the real world. The brain is not in reality mode, it is in a different mode. Thus Holland tells us (2003):

In psychoanalytic terms, Coleridge’s willing suspension of disbelief is a regression to an oral merger of infant and nurturing other in a potential space. In neurological terms, we could say that regression means shutting down some "higher" system that modulates "lower" systems. In the case of the willing suspension of disbelief, the prefrontal cortex inhibits action and the planning of actions so that we no longer are aware of the unreality of the fictions we are dealing with, but it does not - cannot - inhibit the corticolimbic systems that give rise to our emotions. They run freely on, busily prompting us to actions, to approaches and avoidances, we never perform, but the psychological feelings and the physical signs of emotion persist.

Thus it is that in the comfort and security of that mode we can allow ourselves to think and feel as though Nature were Mother.

Note that Holland has invoked Winnicott to explain the mode of literary existence in general (in this he follows Schwartz 1975); not just this particular poem, nor even all poems, but all works of literary art. Thus LTB is itself a kind of transitional object, as is any other poem. This particular poem also happens to be a meditation on transitional objects; but not all poems are like that. We need to be aware of the distinction so that we do not confuse general assertions about poetry with specific assertions about the meaning of this one poem.

In developing this idea Holland notes that, when we are immersed in reading literature, we no longer think of the text as being out there in the world. On the contrary, it is inside us. That can happen, as I suggested above, because language is acquired through a process of internalization. There was a time when all language was out there and coming to us only from others; in particular, it came from mother. What happens when we "relax" into the virtual world afforded by the text is that the sign function "opens up" and once more ushers us into a potential space in which speech is speech by, with, and to mother.

With this in mind let us return to LTB. Starting mid-way in line 26 the poet addresses his speech directly to one of his friends, gentle-hearted Charles. Up to that point the poet is speaking to no one in particular. He is just speaking. For all practical purposes he is speaking to himself, the addressee and addressor are one and the same. Now he speaks to someone. The addressee is no longer the same as the addressor.

To be sure, that someone is not directly present to him. He is only imagining that person. But the person is a long-term and very dear friend. In addressing this friend, the poet suggests how pleasing the sights must be to his friend Charles, who had experienced "strange calamity" while growing up "in the great City pent." That is to say, his friend had grown up in a world cut-off from Nature as he himself is at this moment, imprisoned as he is in the lime-tree bower.

Now consider lines 32-37, which follow his address to Charles. The poet now address himself directly to the natural world:

Ah! slowly sink

Behind the western ridge, thou glorious Sun!

Shine in the slant beams of the sinking orb,

Ye purple heath-flowers! richlier burn, ye clouds!

Live in the yellow light, ye distant groves!

And kindle, thou blue Ocean!

Not only is Coleridge addressing himself to the sun and the flowers and so forth, but he is giving them orders and expecting them to be followed. He has gone from addressing himself to a friend, to directly addressing Nature. When he began the poem he feared being cut-off from Nature. Now he is giving Nature orders.

Furthermore, he does not have to imagine the sun and the ocean in order to address them, as he had been imagining what his friends, Charles in particular, were doing. He can easily do that wherever he is. And so he does it. The act is at once delusional in its grandeur and real in that Coleridge or anyone else, if one accepts the delusion, one can have the conversation at any time and in any place.

Now let us introduce one last passage from Winnicott (1971, p. 89):

. . . the essential feature in the concept of transitional objects and phenomena . . . is the paradox, and the acceptance of the paradox: the baby creates the object, but the object was there waiting to be created . . . To use an object the subject must have developed the capacity to use objects. This is part of the change to the reality principle.

While the poem does not state that the poet created the sun and the flowers, and so forth, it comes very close to it. The poet is clearly acting as though his will had power over the natural world. The stanza concludes with an image of both the poet and his friend gazing at the sun in rapture:

So my friend

Struck with deep joy may stand, as I have stood,

Silent with swimming sense; yea, gazing round

On the wide landscape, gaze till all doth seem

Less gross than bodily; and of such hues

As veil the Almighty Spirit, when yet he makes

Spirits perceive his presence.

This delusion is thus being entertained on behalf of his friend; it is for Charles that Nature must kindle.

At this point the poet has regressed very far indeed. First he gives orders to Nature and clearly expects to be obeyed. Then, having been obeyed, he all but merges with both his friend and with Nature, albeit now conceived as an almighty male spirit. Thus he has now moved through his friend - as conjured up in his own imagination - into contact with the Almighty Spirit. His friend has served as a transitional object between the imprisoned poet and the natural world.

This, I suggest, is the turning point of the poem. Not so much because it is more or less at the mid-point as measured by line-count, but because the distinctions between the poet, his friend, and Nature have all but dissolved in the blazing light. The poem began by sharply distinguishing between the poet, his friends, and Nature; the friends had left him and gone on a walk and he was deprived of natural beauty. That situation has now been remedied, but in an almost delusional way. The rest of the poem will, in effect, once again differentiate the poet, his friends, and Nature, but in such a way that leaves them in mutual contact rather than trapping the poet in isolation. At that point the poem will have achieved its end, thus allowing the reader once again to submit to reality’s rigors and emerge into the mundane world.

There is, however, one problem. I am arguing that Nature here functions as an attachment figure for both poet and Charles. So why is that Almighty Spirit male? One response is that, while an infant’s main attachment figure is usually the mother, that is not necessarily the case; in the right circumstances it could be the father or some other, unusually attentive, male. Further, regardless of the main attachment figure, infants develop secondary attachment figures as well and the father is likely to be among them. Another response would be that we are here dealing with mystical experience and the distinctions and categories of mundane reality simply do not apply. Taken together these considerations seem to me adequate to the case.

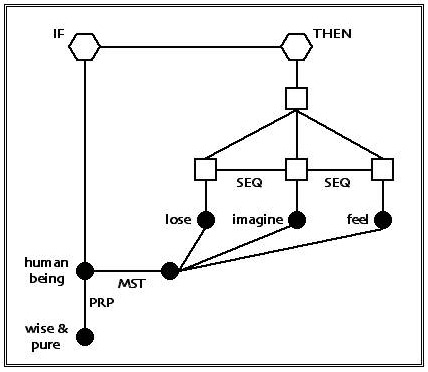

Meaning in "Lime-Tree Bower"

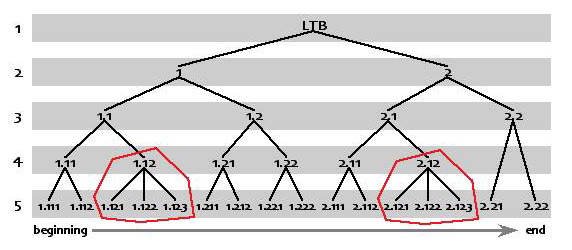

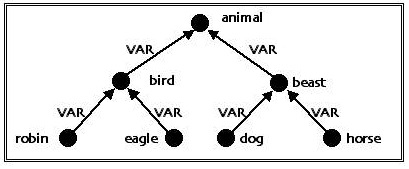

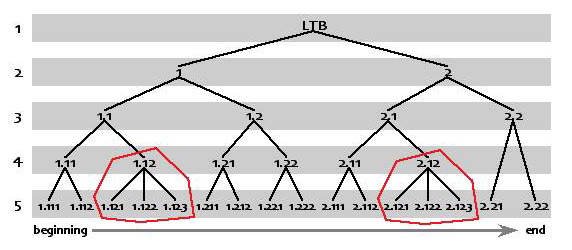

"This Lime-Tree Bower My Prison" presents a first-person narrative presenting the thoughts, feelings, and imaginings the poet had early one summer evening. Coleridge presents the poem in three stanzas (ll. 1-20, 20-43, 43-76), and critical work on the poem has accepted that division at face value. As I have indicated in the previous section, however, I believe that the poem is best analyzed as having two movements, one leading "away" from reality and the other "returning" to it. My first task is to explain, more or less independently of my previous argument, just why I think the poem should be treated s having two movements.

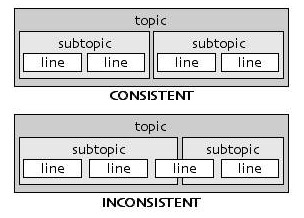

My basic assumption is that poems, and other strings of discourse, consist of big units and small units. The big ones are made of smaller ones and those smaller units consist of still smaller units and so forth. When Coleridge divided this poem into three stanzas he was telling us that it consisted of three large units. When he used periods, exclamation points, and capitalization he was giving us cues about how those larger units are divided into smaller units of the kind we know as full sentences. Some of them are very full indeed. For example, by the standard punctuation and capitalization criteria, a single sentence extends from the end of line five through to the middle of line twenty. I have no quarrel with Coleridge’s sentence-level divisions; but I believe that his stanza indicators misrepresent how those sentence-level units combine into larger units and, ultimately, the whole poem.

I have laid-out my entire analysis in Appendix 1, along with some comments on how I arrived at it. Before making somewhat different comments about that analysis, however, I would like to speculate about why Coleridge divided the text into three stanzas, rather that only two.

In the first place, many poems are written in specific forms that dictate various patterns of stanzas, repetitions, rhyme scheme, and so forth. LTB is not such a poem, nor are any of the other conversation poems. Any stanza division Coleridge offered would thus have to have been grounded in his sense of the "flow" of his material. Secondly, if we look at the breaks Coleridge has made we see that both come mid-line (in lines 20 and 43). As I will demonstrate later on, almost all of the divisions between one topic and the next occur in mid-line rather than between one line and the next. The effect is to minimize any sense of discontinuity between one topic and the next. I suggest, therefore, that Coleridge simply may not have known that the poem consisted of two movements both of which were, in turn, divided in two - with one level of subdivisions beyond that.

For myself, I see nothing strange or unusual about such not-knowing. In my youth I learned to improvise well-formed solos over blues harmonies before I had learned that those harmonies were almost always organized into three four-bar units with fixed relationships between the units. Somehow my "inner ear" figured that out and conveyed the information to my fingers, lungs, and tongue (I play trumpet) without informing me about the details. This seems rather similar to Coleridge’s situation, writing a poem but not recognizing its form.

Basic Shape

Imagine that, when Coleridge published LTB, he had published it without any stanza divisions at all. The text simply displayed a 76-line lump of poetry. How would you then go about determining the poem’s structure?

You would, of course, have to read the poem and see what it says. You would not have to read very carefully to notice that the poem has two relatively short sections that talk explicitly about the poet in the bower, albeit with a very different emotional valence. You might also notice that there are two places in the poem where the sun appears, at the end of the poem and just before the second bower section. At this point you might make some provisional notes, perhaps like this:

While that certainly looks like two sections having a parallel structure, the case would be stronger if those long strings of text between bower and sun, those bracketed somethings, provided further evidence. The first bower section is followed by a scene where the poet imagines what his friends would be doing out in nature. They would, so he imagines, wander around to they came to a particular dell and then they would enter into that dell and become engrossed in observing some weeds on the surface of the water. The second bower section is followed by a scene where the poet, not his friends, inspects what is around him in the bower. Are these sections parallel?

In some ways yes, in some ways no. Both depict fascinated observation of the natural world and both scenes offer contrasts of light and dark. In one case the dark dell contrasts with the yellow leaves of the ash within the dell. In the other we see the foliage appearing transparent in the light contrasting with shadows cast by the leaves. But the observers are different and so are the specific objects of observation.

At this point I would thus hesitate to say that these sections are parallel. I would be inclined to say that they are parallel if they resemble one another more than either of them resembles some other section that we have not yet examined. In the language of deconstructive criticism, we are looking at the play of différance within the text and that requires that we look at the entire field of possibilities, not just local comparisons.

In the earlier portion of the text, the exploration of the dell is followed by a dramatic emergence into "the wide wide Heaven." That is certainly a contrast, from dark to light, from enclosure to open-ness. But it still involves observation of nature. If we look at the latter portion of the text we find contrast there as well, but a somewhat different contrast. After the poet has examined the bower he offers us two homilies, one about Nature’s plenitude - "Nature ne’er deserts the wise and pure" - and the other about the virtues of rising above deprivation. That does not seem parallel with continued observation of Nature.

But that is not all that happens in the earlier portion of the text. After the poet has imagined his friends looking around under the wide Heaven he focuses on one of them in particular, gentle-hearted Charles, and recounts his history of deprivation growing up in the city. Now one might conceive of that as being roughly in parallel to a homily about the virtue of rising above deprivation, for they have deprivation itself in common. Where does that leave us?

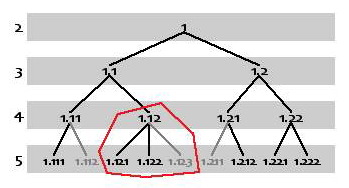

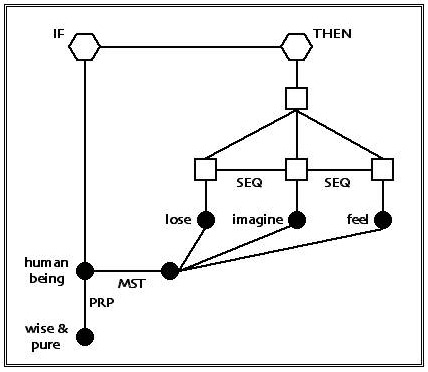

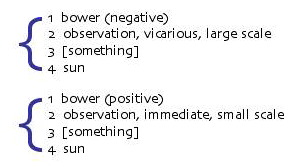

It leaves us still chasing différance around the hermeneutic circle. Rather than trying to run it to ground by continuing reasoning as above, let me declare an Aufhebung and say that I have decided in favor of parallelism between the two sequences. I will say considerably more about these matters in the course of the essay. For now the following diagram indicates where matters stand:

That is, the poem consists of two movements, and each of those involves four blocks of text. Those four blocks of text constitute roughly a middle level in the hierarchical structuring of the text. Those blocks have subdivisions, but are also grouped into blocks of two, like so:

As I have already indicated, you can see the full analysis in Appendix 1. In order to facilitate comparison of the parallelism between the two sequences I have placed them side-by-side in Appendix 2.

Since the first bower-to-sun sequence has the poet following his friends moving about in the wide world beyond the bower I will often refer to it as the macrocosmic movement. The second bower-to-sun sequence, in contrast, is more limited in physical compass and so I will refer to it as the microcosmic sequence. I do not assume that, in order to understand the poem, the reader must explicitly be aware of these parallel sequences and interpret them as such.

When Coleridge inserted stanza breaks, one of them went between the macrocosmic and microcosmic movements. The other went between blocks two and three in the macrocosmic movement, thus:

Note that, in the 1797 text, where the macrocosmic movement is not so well-developed as in the 1800 text, Coleridge did not make this stanza division (see Appendix 3). That earlier text has only one break between stanzas, and that break separates the macrocosmic and microcosmic movements. As I have already said, I do not know why he did not place a break in the microcosmic movement to parallel the one he put in the macrocosmic movement. But the parallelism between the movements is so unmistakable that that is a matter of no consequence.

Mediating Friends

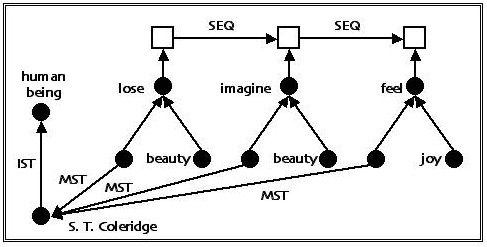

Now it is time to consider meaning in "This Lime-Tree Bower My Prison." My central contention is that LTB’s meanings have the attachment relationship as their foundation. In particular, I will argue that the poet alternates between the two roles available in that relationship, the Child role and the Caretaker role. By implication, the role note taken by the poet is taken by some other entity in the poem.

A second objective is to show how these role changes are managed from one section to the next. Think of this task as analogous to identifying the underlying continuity between a caterpillar and the butterfly it becomes. While they appear to be two different creatures, had one been able to observe closely and continuously, one would have seen the caterpillar enclose itself in a cocoon from which the butterfly emerged. Between the enclosure and the emergence nothing is seen to enter the cocoon, or to leave it. Thus while we are assured that the caterpillar and the butterfly are indeed the same creature - how could it be otherwise if the cocoon has been inviolate - we are left with the mystery of what happened inside the cocoon. Biologists now know a great deal about that mystery. Perhaps neuroscientists will one day provide us with the models we need to explicate the neural mysteries of Child and Caretaker in "Lime-Tree Bower." I propose only to identify which textual caterpillars and butterflies share the same identity and to leave the mystery of metamorphosis to a later generation of scholars.

Third, and finally, I want to show how the overall trajectory of the text can been seen as one moving first away from mundane reality and then returning to it. That circuit constitutes what the psychoanalytic critic Ernst Kris talks of a regression in service of the ego. The midpoint of LTB’s trajectory is the point of maximum regression.

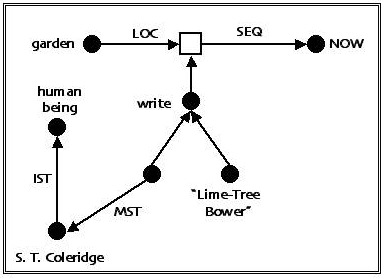

I will conduct this analysis by moving through the poem from beginning to end and focus on the blocks of text I indicated in the discussion of the poem’s basic shape. I will sometimes refer to blocks of text using the numerical labeling system in Appendix 1 and Figure 8 below.

Macrocosm 1: Isolation (lines 1-5)

The poet’s first words are those of loss: "Well, they are gone, and here must I remain." The next sentence, however, asserts that the poet misses the lost beauties and feelings, thus establishing that the poet is cut-off from nature. What is most interesting is that 1.112 projects far into a future of blindness in old age, thus establishing a temporal scope that extends well beyond the time course of the poem itself.

These lines establish the underlying attachment dynamic and place the poet in the Child role and nature in that of the absent Caretaker. Just what role his friends will play has yet to be determined.

When we imagine this opening as some spatial configuration, the image schema (cf. Johnson 1987, p. 126; Lakoff and Johnson 1999, p. 380) for enclosure comes to mind:

Figure 5: Imprisoned in Garden

This schema will re-appear in various ways throughout the poem.

Macrocosm 2: Exploration (lines 5-20)

This block opens with the poet imagining what his friends would be doing on their walk. By asserting that he might not ever see them again he reinforces his sense of loss and contrasts it with the gladness he imagines in them. Just as an isolated Child will go looking for his or her Caretaker, invoking what Jaak Panksepp calls the SEEKING system (1998, pp. 144 ff.), so the poet shifts from distress to exploration, but exploration that is imaginary and mediated by identification with friends who remain in the Caretaker role.

This block unfolds in three sections, as follows:

1.121 Friends wander in gladness, and come to that dell "of which I told."

1.122 The dell is deep and dark and the ash flings its trunk while the waterfall fans the ash’s leaves.

1.123 There friends behold the weeds.

Note that the friends are not explicitly mentioned in 1.122 , which is the longest of the three and devoted to describing the dell’s interior. We can infer that this space is isolated from the world outside, both from its darkness, and by the fact the ash’s leaves "Ne’er tremble in the gale," indicating that fierce winds cannot penetrate into the dell. Note also that the ash is presented as "flinging" its trunk from on place to the next, an active verb that is anomalous but, in this context, very effective. We might also argue that the waterfall is verbally implicated a similar anomaly since the poet describes it as "fanning" the poor yellow leaves.

We should also note that the dell is explicitly characterized as being dark. Not only does this contrast with hill-top wandering of 1.121 and the wide Heavens to follow, but, as Bowlby has noted (1973, pp. 115 ff., 164 ff.) darkness is a natural clue to danger. Children and adults alike are fearful of the dark. This darkness is thus, in Eliot’s formulation, an objective correlative for the anxiety of a poet who feels abandoned by Nature. He is imagining his friends in a natural setting where they might feel an anxiety similar to his own.

Finally, the section concludes by placing the friends in the dell as they examine one specific feature there, the weeds floating on the water’s surface. Given the pains Coleridge took to emphasize how the dell is cut off from the world, I believe that we are to imagine those friends as being enclosed by the dell even as they are fascinated by dripping weeds. Thus the image schema of enclosure is again being invoked:

Figure 6: Enclosure, friends in dell

The poem’s opening image of the poet enclosed in the bower has now given way to that of his friends being enclosed in the dell.

In three steps the poet has moved his friends from the earth’s surface to (something like) its interior. They are thus now well set to re-emerge onto the earth’s surface in a different place. What is happening is that the poet is preparing to assume the Caretaker role in relation to gentle-hearted Charles. By virtue of being fully enclosed within a natural feature of the landscape, the friends are placed into the Child role in 1.123. Since it is Nature that encloses them, Nature must now be in the Caretaker role with respect to them, if not with respect to the poet. That is the situation as we prepare to move from the first to the second of Coleridge’s stanzas, that is to say, from the first two to the second two of the four blocks in the macrocosmic movement.

Macrocosm 3: Reflection (lines 20-32)

Now we have a dramatic change in tone as the friends emerge beneath "the wide wide Heaven" at the beginning of 1.211. They are now in the Child role while Nature is in Caretaker role and the poet is safely in the background observing the broad landscape. The friends are dwarfed by the large landscape, which they merely view; they do not move around in it any more. Note also that we now see a sign of human habitation, the fair bark upon the surface of the sea.

Then, in the next section, 1.212, the poet assumes the Caretaker role from Nature, and addresses himself directly to one of his friends, "gentle-hearted Charles." At the same time the Child role "shrinks" to fit Charles and the temporal scope of the poem stretches back into the past, where Charles’s past is characterized as one of loss and privation, terms similar to those used by the poet to characterize himself in the opening section. The enclosure image thus continues with Charles being enclosed in the city.

This passage bears comparison to a similar passage from "Frost at Midnight," a poem where Coleridge’s infant son takes the role played by "gentle-hearted Charles" in LTB. That is to say, "Frost at Midnight" is literally addressed from father to son, Caretaker to Child. The poem’s third stanza opens with a direct address to his son:

Dear Babe, that sleepest cradled by my side,

Whose gentle breathings, heard in this deep calm,

Fill up the interspersed vacancies (ll. 44-46)

The poet then contrasts his son’s future with his own past, which he describes in terms much like those he used to describe Lamb’s city-bred childhood in LTB:

For I was reared

In the great city, pent ’mid cloisters dim,

And saw nought lovely but the sky and stars. (ll. 51-53)

By contrast, his son will be able to wander the landscape much as the friends in LTB do:

But thou, my babe! shalt wander like a breeze

By lakes and sandy shores, beneath the crags

Of ancient mountain, and beneath the clouds,

Which image in their bulk both lakes and shores

And mountain crags: (ll. 54-58)

As I indicated in my discussion of the nature of poetic space, the effect of directly addressing a character within the poem is to "open up" that poetic space. Specifically, it activates the affective bond the poet has with his friend. The poet has moved from isolation in the opening lines, through fearful fascination contemplating the dell, through delighted interest and now, through direct address, he begins to feel his love for his friend. He is now Caretaker to Charles as Child. He has activated an affective bond that stretches between himself in the bower and his friend out there in Nature.

Macrocosm 4: Invocation (lines 32-43)

The transition from 1.212 to 1.221 ("Ah! slowly sink . . .") is almost as dramatic as that from 1.123 ("dripping edge") to 1.211 ("friends emerge"). Remaining in the Caretaker role, the poet addresses an invocation directly to the sun and the heath flowers, etc. Through that act of command the poet has placed Nature itself into the Child role. Coleridge devotes just over five lines to this invocation, emphasizing its importance. I believe that what is happening, above and beyond manipulation of the Child and Caretaker roles, is the poetic world is becoming dedifferentiated. All that remains is the appearances of things and the sound of the poet’s voice.

As the invocation ends, the poet recovers his self-presence ("So my friend . . .") and, continuing in the Caretaker role, explicitly identifies with Charles - the only place in the poem he does so. Notice that he identifies with Charles in this moment of dedifferentiation where Nature becomes "the Almighty Spirit" and he and Charles become mere "Spirits" - all these Spirits beings having form and thought, but lacking physical substance. At this point Nature is, once again, in the Caretaker role while the poet, along with Charles, is in the Child role.

There is a similar passage in "Frost at Midnight" where Coleridge refers to Nature as the "Great universal Teacher." The tone is much like the LTB’s invocation:

so shalt thou see and hear

The lovely shapes and sounds intelligible

Of that eternal language, which thy God

Utters, who from eternity doth teach

Himself in all, and all things in himself

Great universal Teacher! he shall moul

Thy spirit, and by giving make it ask. (ll. 58-64)

Again, the world has become a matter of sights, sounds, and spirit. In these passages the world has become dematerialized; all that is relevant is shape and color, and sound, whether of the world or the poet’s commanding voice.

Both of these passages, from LTB and "Frost at Midnight," bear comparison with the lines 31-34 of the first movement of "Kubla Khan" :

The shadow of the dome of pleasure

Floated midway on the waves;

Where was heard the mingled measure

From the fountain and the caves.

The effect of these lines is to focus our attention on things that have all but lost contact with physical substance, the reflection of the dome and the sound from the fountain and the caves. These are thus close kin to the shapes and sounds intelligible of LTB and "Frost." But they have been introduced into "Kubla Khan" by an explicit construction - reflected light, heard sound - that is quite unlike the naked assertions of those two poems. And, as I have argued (2003), this construction has associative links all through the poem’s first movement. These lines from "Kubla Khan" are clearly from the same poetic universe as the lines from LTB and "Frost," but they express that universe from a different point of view.

What we have in these passages, it seems to me, is a set of motifs - to use a term that has both musical and folkloric resonance - that Coleridge has used in these poems. The wording is different, and so is the order, but there is a recognizable "core" of meaning for each motif. What is important in the context of my argument is simply that, in "Frost at Midnight" the poet is literally father to the person he addresses in the poem. That is not the case in LTB, but the underlying attitude is the same, not throughout the poem, but in the second half of each movement.

It is further worth noting that Coleridge’s words in lines 32-43 of LTB appear to reflect experiences he seems to have had while wandering about the landscape. A couple of years later he made the some remarks in a notebook about an experience he had while rock-scrambling. He had reached a point in scrambling down a steep precipice where, for a moment, it seemed he could not go back up and the way down seemed quite dangerous (Coburn 1951,p. 235):

My limbs were all in a tremble, I lay upon my Back to rest myself, and was beginning according to my Custom to laugh at myself for a Madman, when the sight of the Crags above me on each side, and the impetuous Clouds just over them, posting so luridly and rapidly to northward, overawed me. I lay in a state of almost prophetic Trance and Delight and blessed God aloud for the powers of Reason and the Will, which remaining no Danger can overpower us! O God, I exclaimed aloud, how calm, how blessed am I now.

The context is rather different from that evoked in LTB, but the words evoke awe and rapture in terms similar to LTB. While utterly passive - flat on his back - Coleridge most actively intends the world round him.

Returning to LTB, we have finished the first movement and the poet has managed to work out of his sense of isolation. Now what? This is about as close as one can get to an undifferentiated world while still having enough presence to score the page with verbal inscriptions. Coleridge has moved far away from a mental state where identities are conserved and assured behind fixed conceptual boundaries. The poem thus cannot continue its trajectory in this - direction, - that is, away from the mundane. It must now start back toward the mundane. And it will do so with the poet, once again, in the Child role and with Nature now acting the Caretaker role.

This section of the poem (1.22) lacks any obvious image of enclosure. If the poet, his friend, and Nature have all become so disembodied that they intermingle freely, how can anything be enclosed or contained by anything else? What happens, of course, is that the poet returns his attention to his immediate surroundings, albeit in a different affective tone. Once again, he will be enclosed within the garden.

Turn Around: Mediating Nature

In the transition from the macrocosm to the microcosm there is, perhaps, a temporal twist. The microcosmic movement begins in this way:

A delight

Comes sudden on my heart, and I am glad

As I myself were there! Nor in this bower,

This little lime-tree bower, have I not mark’d

Much that has sooth’d me.

The first sentence clearly marks a new feeling, delight. I take it that this delight is something that happens after the poet has commanded Nature to reveal its glory to gentle-hearted Charles. Thus I will also assume that that act is a precondition for this delight to have occurred.

Then, with "have marked" in the second sentence, the poet shifts into the present perfect, thus implying that the soothing sights and events he has noted took place in the (immediate) past. Were those sights soothing back then when he first experienced them, perhaps when he was also imagining his friends down in the deep dark dell, or are they now soothing now, but only in retrospect? I am not sure of the answer, nor am I even sure that the question is a reasonable one to ask of a poem. At the same time, I am not inclined to use this as an occasion to begin a triumphal unmasking operation. For me the overriding concern is the order of events as they are set forth in the poem. In the poem itself, the soothing experience is introduced after, not only the dell, but the summoning of Nature’s powers as well. However you call it, the second movement then comes forward in time, once again, to meet the setting sun.

Microcosm 1: Home Base (lines 43-47)

In the wake of his identification with his beloved gentle-hearted Charles, and their coupled ecstasy in the presence of the Almighty Spirit, the poet turns his attention back upon himself and upon his immediate surroundings. The poet remains enclosed in his garden, but the garden is no longer experienced as a place of containment; it has become a comforting presence. Nature is in the Caretaker role and Nature is now present in the bower, soothing the poet. The bower has thus become, in effect, the Child’s secure "home base" in the attachment relationship.

Microcosm 2: Local Exploration (lines 47-59)

Now the poet turns his gaze on the world around him within the bower. Though his attention moves about the bower, exploring it, there is no sense that he himself is moving. This is in marked contrast to the parallel section of the macrocosm where we have a vigorous sense of people moving about the land. I suggest we are experiencing the bower as though we were a contented infant or toddler situated on a blanket or in a crib in the middle of a garden so hushed that he can hear the buzz of a single bee. Or, if your inner psychoanalyst is so inclined, think of a Child examining his mother. Now that Nature has been summoned to activity in the first movement, she is fully alive, and has become the Child’s Caretaker.

Like the exploratory section of the macrocosmic leg, this one has three components as well:

2.121 Looks at the leaves and the patterns of light and dark.

2.122 Focuses on the walnut trees, the ivy, and the elms.

2.123 The humble-bee sings in the bean-flower.

Again we have a play between images of light and dark, and again something in Nature is "activated" through Coleridge’s choice of verb. In this case it is the ancient ivy "which usurps [the] elms [and] makes their dark branches gleam a lighter hue."

What is most interesting, however, about this section is that, for the first time in the poem, we see animal life, a bat (perhaps a touch of the sinister echoing the darkness of the dell), a swallow, and the humble-bee. Something new has entered into the poetic universe, as though we are beginning to see some differentiation. Having recovered his bond with Mother Nature, animal life is now differentiated from life in general, preparing us for further differentiation.

That humble-bee is clearly enclosed within the bean-flower, just as the poet’s friends were enclosed within the dell in the first movement. The physical scale is different by a factor of 100 and more, and so is the mood - this flower is not a dark and mysterious place within the earth; but the topological structure of the image is the same, something living is enclosed within something else that is living. As in section 1.123, we have the image schema of enclosure, this time the bee within the flower. That enclosure clearly differentiates and separates the bee from the rest of the natural world.

I suggest that, just as enclosure in the macrocosmic movement cast the friends into the Child role with respect to Nature, so enclosure does with the bee, a bee happily feeding within the flower - at which point I rather imagine the traditionalist psychoanalytic Jimminy Cricket on my shoulder is thinking, "Shazaam! the infant at mother’s breast!" Now that the bee, not the poet, has become the carrier of the Child role, the poet is free to move into the Caretaker role in the next block and to emerge into a wider world.

Microcosm 3: Reflection (lines 59-67)