Literary Morphology: Nine Propositions in a Naturalist Theory of Form

by

William L. Benzon

August 10, 2006

Naturalist literary theory conceives of literature as an adaptive behavioral realm grounded in the capacities of the human brain. In the course of human history literature itself has undergone an evolution that has produced many kinds of literary work. In this article I propose nine propositions to characterize a treatment of literary form. These propositions concern neural and mental mechanisms, and literary evolution in history. Textual meaning is elastic—through not infinitely so—and constrained by form. Form indicates the computational structure of the act of reading and is the same for all readers. Over the long term, literary forms become more complex and sophisticated.

The Naturalist Study of Literary Form

There are signs that the study of literature has begun recognizing the cognitive and neurosciences and evolutionary psychology, each a loosely organized arena of intellectual activity that has flourished in the last three decades. Empirical work continues being published on how people understand literary texts while the Stanford Humanities Review devoted an entire issue to cognitive criticism, taking at article by Nobel laureate Herbert Simon (1994) as its point of departure. Poetics Today has had special issues on cognitive poetics; Philosophy and Literature has been friendly to Darwinian thinking for perhaps a decade; book-length studies and anthologies are becoming more common, as are conferences.

Much of this work is theoretical and programmatic in nature, suggesting models, modes of explanation, and ways to proceed but not analyzing specific texts or groups of texts in any detail. Practical criticism inspired by these newer psychologies is, like most current practical criticism, concerned primarily with the meaning of texts. My emphasis is different. I am interested in form, in morphology. The purpose of this essay is to explain and justify that orientation and, in particular, to indicate why the newer psychologies provide an opportune conceptual environment in which to explore literary form.

There is nothing new about the study of literary form. But the term is ambiguous, between "literary form" as a kind of literary work, and "form" as differentiated from content. Sorting out the ambiguity is not easy.

Some ideas about form are basic to all study of literature, such as the existence of comedy, New and Old, tragedy, romance, lyric, and epic—discussed in such standard works as Northrup Frye’s Anatomy of Criticism and, more recently, Alistair Fowler’s Kinds of Literature: An Introduction to the Theory of Genres and Modes. Beyond these we have the categories that line the aisles of the popular fiction (as opposed to literary fiction) sections of bookstores: Fantasy, Romance, Science Fiction, Mystery, Horror, and their subtypes. All of these are literary forms, kinds of text; but discussions of them typically address matters of content as well as form.

Students of poetry can turn to handbooks detailing poetic forms, e.g. Lewis Turco’s The Book of Forms: A Handbook of Poetics, which in its third edition has well over 300 pages and describes I don’t know how many poetic forms—I own the 160-page first edition and it has more forms than I care to count. These forms are characterized in traditional terms, meter, stanzas, rhyme, number of lines and so the handbook is mostly about form as differentiated from content. This is not a theoretical treatise; it is a practical handbook, intended for poets and for those who need a way to describe the formal aspects of poems.

While my discussion has some overlap with those discussions, my intention and focus are different. Unlike the handbooks, my aim is methodological and theoretical, not descriptive. The intellectual program I outline might well have implications for discussions of literary kinds, but I do not take the sorting out of kinds as my starting point. My starting point, rather, is with the newer psychologies and how they can help us analyze the formal aspect of literary works. As that project proceeds it may well help us sort of literary kinds, but I cannot see that far into the future.

Turning to the task at hand, I have organized this essay around nine propositions, some of which are hypotheses susceptible to and requiring empirical and/or computational confirmation (i.e. simulation, cf. Benzon and Hays 1976: 271-273) while others seem to be facilitating assumptions: "if we start from here, then we can get somewhere." As I sometimes find it difficult to tell the difference, I leave that as an exercise to the reader.

0. Proposition: I will indicate these ideas with this formatting. All of these propositions are listed, in order, in an appendix at the end of the essay.

I have come to think of this work as critical naturalism. While I am not entirely happy with the term—"the natural" is a problematic notion—I prefer it to thinking of this work as deriving from some species of psychology. The problem is that none of these psychologies in themselves has much to say about literature. I find that one has to do quite a bit of conceptual construction to bridge the gap between what those psychologies can comfortably deal with and literature itself, especially literary form. Thus while I have made extensive use of those psychologies, I do not feel that my analytic and descriptive work is of them; it is only commensurate with them.

When I talk of critical naturalism I am thinking of biology as a disciplinary model. Biology involves the study of forms and their diversity, where that diversity is the result of a historical process, evolution. Biology is also, in the words of my colleague Timothy Perper, the study of worlds within worlds; there is the ecosystem within the environment, and the organism within the ecosystem. Some organisms are many-celled, and some are single-celled; in both cases we must study anatomy and physiology. When we study the anatomy and physiology of single cells are studying molecules and molecular processes. The most remarkable of those molecules are those of DNA and RNA; it is these molecules that make life possible. In the very small, biology is about how those molecules reproduce themselves and construct other molecules. In the very large, biology is about how vast populations of those molecules interact with one another through the mediation of phenotypes and environments.

To a first approximation, literature is like that. We have a large diversity of forms embedded in an intersecting multitude of histories. Works must be analyzed in the small, e.g. individual tropes and phrases, and the large, e.g. sonnet cycles and multi-volume novels. Where the biologist examines tissues and molecules, the naturalistic critic interrogates the mind in its brain. Considered one at a time, works yield analyses and readings. Considered in the many, we have periods and movements. Both biology and literature have a mystery at the heart of things, that of origins.

First I offer a general rationale for emphasizing the study of form rather than of meaning. After that I consider the embodiment of literature in the brain. Then we move to the conceptual heart of this essay, that literary works be analyzed as computational forms. I conclude with the long-term evolution of literary forms in human history.

Practical Criticism and Its Vicissitudes

While this essay is about theory and method, its ultimate commitment is to practical criticism. It is not simply that a theory is of little value unless it provides guidance to the practical critic but that a theory cannot even be constructed and elaborated without interacting with a substantial body of practice. Literary theory ultimately rests on the analysis of literary works and their circulation in minds and social groups. Given that, I want to examine the problem of practical criticism in as neutral a way as I can.

The practical critic, it seems to me, starts with the intuition that there is something very important going on in literature that is not obvious. Just how the "not obvious" is conceptualized varies from one critical methodology to another, but, as I am trying to make a neutral statement, I do not want to worry too much about the differences among all those characterizations. All that concerns me is that the practical critic seeks to discover something that is not obvious.

Let us say that what the critic is looking for is a pattern, one that bears the impress of the various "forces" shaping the work, whether they are biological or cultural, individual or socio-political, universal or locally contingent. On the one hand, literary works are very complex; they have many parts, many traits, and can be described in many ways. They exhibit many patterns. On the other hand, the human mind is extraordinarily good at seeking and finding patterns. And we can readily find patterns for things that are not there, not really. Is that face on the grilled cheese sandwich really the Virgin Mary, or is it merely the wishful whim of a true believer in search of miracles? Are those really a Big Bear and a Little Bear in the northern sky? What is that streak on the photographic plate? It wasn’t exposed to light, so how did that happen? Is it a freak occurrence or evidence or some recurrent regularity in the world?

Faced with the unlimited variety of patterns one can discern in a literary work, the practical critic needs a systematic way to eliminate most of them from analytic consideration. Hence critics have invoked authorial life and intention, historical context, the unconscious mind as construed in various psychologies, universal mythological patterns, a society’s means of production (broadly construed), and so forth. All of these rationales, and others, have been invoked to constrain the field of patterns that must be considered. In arguing for the newer psychologies I am simply casting them in the role of Provider-of-Constraint. I also happen to believe that they can do better service in that role than existing alternatives. That, however, can only be decided through practical criticism. I can make various arguments, but the final verdict must inevitably be in the hands of practical critics who adopt this perspective in their analytical work.

In offering the newer psychologies for use in this way, I am concentrating on the examination of literary form. In so doing I do not mean to imply that I believe that to be their only use, or even their only good and proper use. Though I believe these psychologies are useful in the examination of content, I am concentrating on form for several reasons. In the first place, as I have already indicated, the study of form has been neglected in both practical and theoretical work grounded in these newer psychologies. In the second place, these newer psychologies are not well-developed for the study of literature or of literary form. Thus here is an opportunity for students of literature to contribute to these newer psychologies. To make such contributions, however, we have to speak in terms that are commensurate with those of the newer psychologies. And so we must learn something about them and use those terms in our analytical and descriptive work.

There is a third reason. I believe that literary form places strong constraints on the mind-brain that experiences the text. This is not at all a new idea; one can find it, for example, in the work of Gregory Bateson (1972, pp. 128-154). Robert Rogers (1985), David Miall (1988), and Reuven Tsur (1992). If form imposes constraints on readers, then it seems reasonable to believe that explicit knowledge of form will provide practical critics with guidance in their search for patterns in the not obvious.

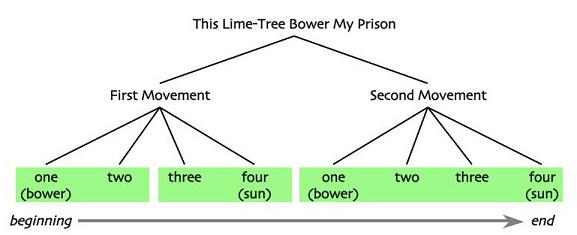

Let us consider a specific example, Coleridge’s "This Lime-Tree Bower My Prison". The published version of the poem consists of three stanzas; this division into parts is a simple aspect of the poem’s form. I have recently argued (Benzon 2004), however, that the poem actually consists of two major movements. This is an assertion about form, but one that is at odds with the ostensible form of the published text—though not with the form of a somewhat different unpublished text, which has two stanzas. I made that argument by attending to the poem’s meaning.

I noticed that the poem focuses on the bower in two places, at the beginning of the poem and at the beginning of the third stanza. Similarly the sun is evoked at two places, the end of the second stanza and the end of the poem. Thus the poem appears to consist of two successive movements, each beginning in the bower and ending with the sun. By attending further to what happens in those movements and to sentence-final punctuation, I concluded that each movement consists of four parts, and the four parts in the two movements are in parallel (see Figure 1 below, stanzas are indicated by green blocks). The first stanza of the poem contains the first two parts of the first movement, while the second stanza contains the second two parts. The third stanza is devoted entirely to the second movement.

Figure 1: Constituent Structure in "This Lime-Tree Bower"

That "Lime-Tree Bower" consists of two movements, each consisting of four parts, with the corresponding parts in parallel—that assertion is about its form. It tells you nothing about what the poem means, but it indicates some of the constraints acting on a mind that is reading the poem. No matter who reads the poem, the meaning they construct will involve the elements of those two movements.

Those two movements, with their four parts each, are an aspect of what I will call the poem’s constituent structure later in this essay. The bower itself, along with the sun, the poet, his friends, and a flying bird, these are all aspects of the poem’s armature—a term I adapted from Lévi-Strauss (1969, p. 199). While those two facets do not exhaust formal considerations—for many others, see Tsur 1992—they are among the most important formal features, and all literary works exhibit them. Literary works exhibit other formal aspects, but not all texts exhibit all of these features. The features associated with versification are an obvious example; patterns of rhyme and meter are not relevant to the study of prose texts.

In thus talking of reading, constituency, and armature I do not mean to invoke conscious and deliberate activity on the part of readers, much less the often protracted process by which literary critics produce published analyses and interpretations of texts. Most of what happens in reading is unconscious. Thus, one of the conceptual motifs of the cognitive sciences is that of the cognitive unconscious (cf. Lakoff and Johnson 1999, pp. 9-15). Most of our perceptual, conceptual, and affective processes are largely unconscious and, as such, not susceptible to deliberate notice and manipulation. The processes by which a mind reading "Lime-Tree Bower" apprehends the two movements, and the parts in each, is not a deliberate conscious process. It simply happens as a natural consequence of the way the mind apprehends texts. In contrast, the process by which a critic explicitly identifies these components, requires that one look at a text in a certain way, one that regards a text as a hierarchical structure of units which are considered to reflect the hierarchical structure of the underlying mental process. I am proposing that the newer psychologies justify this mode of analysis (cf. Alvarez-Lacalle and Dorow 2006) and will say more about this later on.

Returning to the poem, I further note that my examination of the poem did not stop with its constituent structure. I went on to offer a fairly elaborate speculation about the psychological mechanisms underlying the poem’s meaning. Here I touched on John Bowlby’s attachment theory, Winnicott’s conception of the transitional object, Vygotsky’s account of language acquisition, the notion of an image schema from cognitive linguistics, and various other ideas and observations from the cognitive and neurosciences. Thus, while this essay is about the newer psychologies and literary form, I do not think that their value, or intellectual responsibility, is confined to form. I think we must attend to the whole work and I have strong preferences about how to think about content, about meaning and feeling. But those preferences are not in play in this essay except as they follow from the type of formal analysis I propose. I do believe, moreover, that there is some measure of independence between the formal analysis of a literary work and the problem of analyzing and explaining that work’s content, or meaning. Thus a critic could accept the formal analysis I have offered for "This Lime-Tree Bower" while proposing a different account of its content.

In thus proposing to focus on literary form I am, in effect, proposing that we rethink the nature of a literary work. "Text" has come to be the generic term for such works, even oral performances. We know that such texts have physical form, but that the meaning is not, in any simple sense, carried within the text, as wine in a bottle. According to a conventional doctrine, which I accept, the relationship between the signs in a text and their individual meanings is considered to be arbitrary. It is up to the reader, then, to provide those signs with meaning. Societies devote considerable effort to ensuring that their members attribute mutually consistent meanings to linguistic signs, but the process is not a perfect one. And so different people will experience different meanings from texts, literary texts among them.

While true enough, this view is not adequate to the study of literature. I believe than we must construe the literary work to be, not merely a text consisting signs inscribed on some surface, be to be a largely unconscious computational form consisting of a constituent structure and an armature. In making this assertion I want to emphasize that I do not accept the computational metaphor in perhaps its commonest form, that the mind is a specifically digital computer. The general idea of computation is more general and more abstract than that (cf. von Neumann 1958, Minsky 1967, Wolfram 2002). I have explicitly argued against the digital metaphor (Benzon 2001) and do not regard it as essential. For my present purposes it is sufficient to say that I view computation in the broadest possible sense.1 What is essential is that the computational metaphor implies physical embodiment, which in turn implies action in time. All real computation takes place in physical devices and in real time; as such it is limited by computational resources, such as the number of computing devices and time available to complete the computation. If I were arguing in terms of Walter Freemans’s neurodynamics (1995, 1999, 2000) I might use a different term, dynamic form, or even intentional form. But I believe that computation is the best term for my purposes in this paper.

Finally, I should make a remark about genre as that is the standard rubric under which literary criticism attempts large-scale systematic treatment of forms. My first remark is simply that the problem is a very complex one, as one can verify through even a cursory look at Alastair Fowler’s Kinds of Literature: the Theory of Genres and Modes. Secondly, genre theory does not confine itself to formal traits as I am defining them. Kinds such as comedy, tragedy, and romance are more matters of content than of form—in the sense I am using the term. And such a very important and problematic genre as the pastoral demands fairly specific kinds of content. Thus, while I expect that more scrupulous attention to form may well provide insight into the general problem of literary kinds, I would not predict any blinding illuminations resulting in sudden resolution of the problem.

Embodiment: Literature in the Brain

Let us begin with the famous phrase that Coleridge published in Chapter XIV of the Biographia Literaria: "that willing suspension of disbelief for the moment that constitutes poetic faith." In 2003 Norman Holland published a neuro-psychoanalytic account of that suspension, arguing that when we read a literary text our perception of both our bodies and our environment is diminished, "we no longer judge probability or reality-test" and that "we respond emotionally to the fiction as though it were real." I believe that these observations are, in the main, valid.

For me the critical passage in Holland’s essay comes when he observes that "brains serve one overarching purpose," namely, "to move a body." Holland goes on to observe that we are generally static when "absorbed in a movie or play or book" and that:

Reality-testing, it turns out, is also related to planning movement and action.

To intend to act, to plan a movement, we imagine the outcome. If I plan to move that glass of water on the table, I have to imagine where it is going to be after I have moved it. I have to imagine what is not now true—a contrafactual. I understand where the glass now is—the reality of the glass—by noting where it is not. Having moved the glass, I know where it is by remembering where it was, again something no longer the fact.

Some minor qualification is necessary. After all, when reading we are generally sufficiently aware of our surroundings that, for example, we turn on a light when it grows dark, change our posture to prevent cramping, and so forth. But these things are not directly related to what is transpiring in the text. In our mind’s eye we may be perceiving ladies and gentleman at a courtly dance or sailors chasing a whale, but in reality we are relatively still. Such movements as we make are decoupled from the story we are reading.

This is all obvious enough, even trite. Holland’s point, however, is that, considered as an activity of the brain, reading texts involves an overall constellation of activities that is quite different from those in play when we engage directly in the business of living in the world. The same, obviously enough, is true when we are dreaming. We are detached from the external world, but the sensory areas of the brain are quite active, as are motor areas, though we move very little. That is because the motor impulses are blocked from reaching the body, and so it remains at rest (Hobson 1999). That literary experience is, in effect, a waking dream is a commonplace notion. It remains to be seen to what extent the reading of books and the viewing of plays and movies is, in any useful technical sense, significantly like dreaming (cf. Panksepp 1998 pp. 134-135, Benzon 2001, pp. 160-164). I bring it up primarily as another example of an overall pattern of brain activity being associated with a specific mode of experience.

Beyond this, there is a constellation of social conventions governing how we "consume" texts, how we talk about them with others, how, if at all, we integrate their lessons into our lives. These conventions have roots in our early childhood, both in play, and in listening to stories told to us by our parents and others. If one includes pre-linguistic babbling and the mother-infant play organized around that along with similar activity, one might even argue that the roots on aesthetic play with language are deeper than the use of language to accomplish the mundane tasks of living. However one might argue that specific point, the larger point is simply that literary behavior is learned behavior with roots in early interactions between the infant and others. The brain is trained in the ways of stories and rhymes.

By extension, I suggest that the properties of all literary texts are suited to the capacities of the brain as it is in the state of special receptivity that Holland describes. One of the characteristics of these texts is that they must allow for a suitable resolution when one has reached the end of the text. Texts have endings and they have definite beginnings as well, and middles too; Aristotle observed as much over two-millennia ago. This is a formal property and does not depend on having specific content or meanings for the film, or text. In this age of cognitive science this commonplace notion gains a new valence from the idea of computation. All real computations take place in time. Just how much time a computation will require, and even whether or not it will ever come to an end at all, is a matter of both practical and theoretical concern in computer science (see, e.g. Minsky 1967). I will say more about computation later on. For now I want to make one point, that the neural computation involved in one’s primary experience of a text must come to an end at some point. When that happens one can then "exit" the literary mode and re-engage the ordinary business of life, with the appropriate reallocation of neural resources to activing and perceiving in the external world.

Returning to Holland, he does not postulate some literary module in the brain. Rather, he looks to the overall pattern of activity. That is the approach I take here, with the additional observation that that pattern of activity is learned and that literary texts are crafted to suit it. With this in mind, I offer the first hypothesis:

1. Literary Mode: Literary experience is mediated by a mode of neural activity in which one’s primary attention is removed form the external world and invested in experiences prompted by the text. The properties of literary works are fitted to that mode of activity.

Given that literary experience is subserved by a certain disposition of neural resources, we might wonder whether or not the neural tissue that supports imaginary experience is the same as the tissue that supports real experience. My view on this issue was suggested by the elegant cybernetic theory of mind outlined by William Powers (1973: 222-226). The brain is full of schemas for perceiving, acting, and thinking. The content of literary works draws on exactly the same schemas as are used in mundane life (cf. Miyashita 1995; Grueter 2006; Benzon 2000). Thus, when I created a semantic model to investigate the meaning of Shakespeare’s sonnet on "Th’expence of Spirit" (Benzon 1976, 1981) I was implicitly asserting that the high-level sexual circuitry activated by that poem is the same circuitry activated in real-world sexual activity.

By pushing this idea a bit further we arrive at another hypothesis:

2. Extralinguistic Grounding: Literary language is linked to extralinguistic sensory and motor schemas in a way that is essential to literary experience.

Literature is not disembodied language (cf. Lakoff, 1987, Turner, 1996). It is language that evokes images and sounds and the semblance of physical movement. We may sit still when we read, or listen to a story, but we understand the movements of characters from one place to another because we ourselves know what it is to move about. We interpret the gestures and actions we are told about through our own experience of similar gestures. And so it is with the signs and sounds and smells and tastes, not to mention feeling as well. We can no longer afford to regard such sensorimotor grounding as somehow secondary in literary experience. It is essential (cf. Esrock 1994). The sense of this proposition is simply to deny the existence some non-corporeal and transcendental realm of meanings.

The fact of neural embodiment has some fairly general implications that are worth a moment’s reflection. In the first place, it implies that the meanings readers find in texts will necessarily be grounded in their social, historical and personal context. Brains mature in specific contexts and bear the imprint of those contexts. The formal properties of literary texts do not exempt their readers from the necessity of living in their worlds. A brain "trained" in 16th century Britain is going to be different from one "trained" in mid-twentieth century California. On that ground alone one would expect two such readers to experience different meanings in the same texts. But, I will argue in the next section of this essay, the form of the work will be the same for both readers.

Paradoxically, neural embodiment also gives literary culture a measure of independence from the contingencies of immediate historical context. The brain is not a tabula rasa. While it responds to the imprint of its immediate environment, it does so with internal structures and processes that have been shaped by millions of years of evolutionary history. Those structures make their own demands on the world and thus allow for some negotiation between biology and society. The long-term trace of that negotiation, I will argue in the last section of this essay, is the profusion of forms and texts that constitutes literary history.

Finally, consider the sentiment is expressed in the shopworn final line of "Ars Poetica" by Archibald MacLeish: "A poem should not mean/But be." The idea is that literary works afford a certain kind of experience and that attempts to explicate their meaning are beside the point. In this sense our experience of literature is as inaccessible to language as our experience of dreams. The fact that literature is expressed in texts that we may examine at will does not matter. For it is only when we apprehend the text from within a literary frame of mind that we can experience its meaning and significance. We can we remember and talk about texts we have read, as we can remember and talk about our dreams. But in neither case does the talk restore or recover the primary experience. To borrow a line from Coleridge’s preface to "Kubla Khan," as soon one has finished reading the text, the experience itself dissipates, "like the images on the surface of a stream into which a stone has been cast."

I am thus sympathetic to Hans Ulrich Gumbrecht’s recent Production of Presence (2004), where he argues that the experience of literature itself is one of presence, while the writing of criticism, the search for literary meaning, is quite different. It is not an experience of presence. However obvious this may seem, we need to recognize that, in the past few decades, criticism has forgotten this. For example, three decades ago Geoffrey Hartman (1975, p. 268) asserted bluntly: "Reading, then, includes reading criticism." More recently Tony Jackson (2003, p. 202) has said: "That is, a literary interpretation, if we are allowed to distinguish it as a distinct kind of interpretation, joins in with the literariness of the text. Literary interpretation is a peculiar and, I would say, unique conjunction of argument and literature, analytic approach and art form being analyzed." However common they are, these ideas seem deeply mistaken to me. The conjunction they imply between text and critical reading is but a nostalgic way to frame literary interpretation. Our task as literary critics in the age of the cognitive and neurosciences is to not explicate what individual texts mean, but to understand how they shape the experience of reading. That requires, among other things, that we undertake an examination of form with the ultimate goal of understanding how the formal properties of literary works are apprehended by the brain.

Computation: Literature in the Mind

While I am favorable to the view that the mind is what the brain does, I am not sure what that gets us in the absence of a deep understanding of just what it is that the brain does. Ever since reading on neural holography (1971) I have been convinced that what the brain does is strange enough that we need concepts and language about mental entities and events. The laws of mental entities must be consistent with those of brains, but they are not derivable from them.2 In private conversation David Hays and I talked of implementation as the relationship between mind and brain: the mind is implemented in the brain (Benzon 1997).

For some purposes it is useful to talk about words, for example, as indivisible objects. For other purposes, however, we may need to go further and make a distinction between the signifier, where a word is considered as being constituted by phonemes, syllables, and morphemes, and the signified, semantics—however one conceives that. Considered as a neural entity, however, even a syllable is a complex thing, having a vocal motor aspect and an auditory aspect, each of which is itself distributed over a complex neural meshwork. While it is convenient for us to think about e.g. syllables as unitary things, as implemented in the brain they are complex neural processes. One could say the same thing about literary characters. The representation of even an imaginary person will be dispersed over many brain regions, making such a representation a very complex neural entity indeed. Yet it is often useful to think about characters as unitary objects. The multiplicity that exists in the brain often seems, to the mind, to be a coherent unity.

This phenomenon is often discussed as the binding problem, which has received considerable discussion within the neuroscience community (Triesman 1996, Freeman 2000). What I am suggesting, however, is that the phenomenon of binding be interpreted as evidence of the mind at work. If you will, it is this capacity for binding that allows a nervous system to implement a mind.

We should also consider Eleanor Rosch’s (1997) sharp observation that experimental psychology has neglected any consideration of William James’ stream of consciousness, a neglect, so far as I can tell, that extends to the recent resurgence of work on consciousness in philosophy and psychology. It is not simply that language processes, for example, are complex, but that when we are talking we are at one and the same time observing the addressee, taking note of the flies gathering on the strawberry shortcake, the gulls flying across the sun, and the infant’s cry from across the street. All of these are interleaved in the stream of consciousness, and yet we manage to keep a conversation going in a coherent manner (Benzon 2001, 71 ff.; 2003a). That is the mind at work and, for all the advances we have made in understanding the brain, the mind—what the brain does—remains a mystery.

Beyond this we must take account of the fact that, while the human nervous system is pretty much the same in all human populations, and has been so for the last 100,000 years or more, culture varies considerably among populations (cf. Spolsky 2002, p. 46). There is, moreover, considerable variation among cultures in the formal and informal institutionalization of access to altered states of consciousness (Furst 1972, Winkelman 1992) and in the use of external supports for mental activity (e.g. image-making, writing, calculating devices, etc., see Donald 1991, Hobart and Schiffman 1998). These differences have to do, not with the brain, but with how the brain is used; these are mental differences.

Literary form is the trace of literary mode as characterized in the previous section. When we examine literary forms, we are observing traces of the mind in motion. The study of literary form is to a naturalist criticism as the study of animal form and anatomy is to zoology. Unlike anatomy, however, literary form is not spatial, it is temporal. Literature unfolds in time. That is why I have chosen to consider form under the rubric of computation. Computation is irreducibly temporal.

Computation and the Cognitive Sciences

While the temporal nature of literary experience is one reason for taking computation as a model for literary process, it is not my only reason for so doing. More generally, the idea of computation provided much of the excitement and energy in the early years of the cognitive sciences. As Ulric Neisser remarked thirty years ago (1976, pp. 5-6):

. . . the activities of the computer itself seemed in some ways akin to cognitive processes. Computers accept information, manipulate symbols, store items in "memory" and retrieve them again, classify inputs, recognize patterns, and so on. Whether they do these things just like people was less important than that they do them at all. The coming of the computer provided a much-needed reassurance that cognitive processes were real; that they could be studied and perhaps understood.

Much of the work in the newer psychologies is conducted in a vocabulary that derives from computing and, in many cases, involves computer simulations of mental processes. Prior to the computer metaphor we could populate the mind with sensations, perceptions, concepts, ideas, feelings, drives, desires, signs, and so forth, but we had no explicit accounts of how these things worked, of how perceptions gave way to concepts, or how desire led to action. The computer metaphor gave us conceptual tools through which we could construct explicit models.

Though it is an odd way of putting it, one might say that it is the computer metaphor that laid the groundwork for the currently fashionable notion of embodied cognition. That formulation is odd on two counts. In the first place, much of the rhetoric of computation talks of information and information processing in such a way that almost sounds as though information were not physical. The important point, of course, is that any given "chunk" of information can take different physical forms—marks on paper, voltage spikes in a circuit, polarized regions in magnetic form, etc.—but always, information is physically embodied and so available for use by the appropriate physical system. In the second place, at least some proponents of embodied cognition see their work in opposition to earlier versions of cognition that are tightly bound to notions of information and computation (cf. Lakoff and Johnson 1999, pp. 74 ff.). I take this confusion as evidence of the provisional state of our investigations.

However much inquiry has followed from application of the idea of computing to the understanding of human behavior, we are a long way from a consensus psychology built around the idea of computation. Nor does one seem to be on the horizon. It is very much a work in progress.

That being the case, how can one employ the idea of computation in the study of literary form? First I wish to make a simple observation about computation as it is currently understood. Computation is not essentially or even primarily about number and quantity. For most of us, arithmetic may be what comes most easily to mind when we think of computation. Arithmetic is certainly computation; but when we are doing it, we are actually manipulating symbols according to well-defined rules. We have symbols that stand for numerals (zero through nine) symbols that stand for operators (plus, minus, times, divide by, and equals), and the decimal point. When we manipulate these symbols in certain ways, we perform calculations. No more, no less. In the current understanding, computation is symbol manipulation as embodied in the abstract notion of a Turing machine and similar conceptions (cf. Minsky 1967). But this notion itself is too general to give us specific guidance. A good computational model of natural language would be obviously be useful. Despite considerable investigation going back to the 1950s, however, we do not yet have such a model. Nor is it obvious that such a model would be sufficient, for as our second proposition asserts, "literary language is linked to extralinguistic sensory and motor schemas." And that implies that a computational model for literary texts must deal with extralinguistic matters as well. And so we have worked our way back to the notion that we do not yet have a consensus psychology grounded in the idea of computation.

In this situation I can see little recourse but to proceed informally. I have already mentioned some basic concepts in my discussion of Practical Criticism and Its Vicissitudes. In the next section I will develop those concepts primarily through the notion of a relational network (cf. Norman and Rumelhart 1975). Imagine a spider’s web. The junctions between threads are called nodes and represent concepts while the threads themselves are called links and represent relationships between concepts. Such models are widespread in the cognitive sciences and have been developed in many different domains.3

Processes in Networks

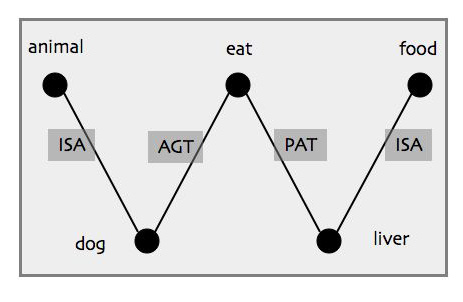

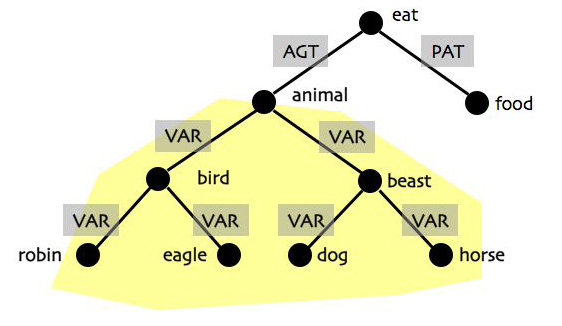

One of the primary objects of literary computation is simply to compose meaning, on the fly, from the succession of words in the text. This is not the only computational process—we must also consider the sound and rhythm of those words, we must consider style—but that is what I want to concentrate on in this section. Let us think of lexemes (that is, words) as being represented in a relational network. In Figure 2 dog would be linked to animal through an ISA link (dog is an animal) and to eat by an AGENT (AGT) link, while in the same subnetwork liver is linked to eat by a PATIENT (PAT) link (dog eats liver), and so forth through all the types of concepts and relationships.

Figure 2: Relational Network of Lexemes

The information depicted in this figure could also be represented as a set of propositions, as follows:

ISA (dog, animal)

AGT (dog, eat)

PAT (liver, eat)

ISA (liver, food)

Here we have four propositions, one for each of the relations depicted in the figure. Each proposition consists of the name of a relation (corresponding to a link in the diagram), over two arguments enclosed in parentheses (corresponding to the nodes at either end of the link). The order of the arguments corresponds to the direction of the relationship between them. Dogs are animals, not the reverse. When such networks are programmed on a computer, propositional forms are used.

The network depicted in Figure 2 is small and quite simple; think of it as a fragment of a larger network. The networks used in computer simulations of human thinking are quite large, but like that in Figure 2, they are composed of simple parts connected to one another in simple ways. In the work I did with David Hays we distinguished between sensorimotor schemas, on the one hand, and cognitive networks on the other (Benzon 1976, 1978, Hays 1981). Things like dog, pine tree, walk, salt, and so forth, things one can apprehend with the senses, would be characterized by sensorimotor schemas, and those schemas would, in turn, provide the foundation for nodes in the cognitive network. Thus the dog, eat, and liver nodes in Figure 2 would be associated with corresponding sensorimotor schemas. We also had mechanisms for defining abstract concepts over patterns in cognitive networks (Hays 1976, Benzon and Hays 1990a).

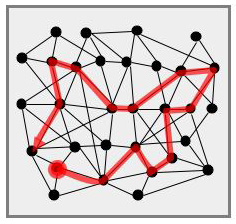

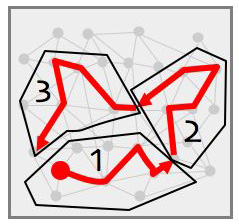

For our immediate purposes, however, the important point is that two general classes of operations can be defined in networks, path tracing and pattern matching (Hays 1977). These processes involve changing the states of the nodes in a network, e.g. from quiescent to active. In Figure 3 we see some network in which a particular path is highlighted; those nodes in that path are said to be active while the other nodes are quiescent. It might, for example, might trace the opening of Shakespeare’s sonnet 129, "The expense of spirit in a waste of shame/Is lust in action . . ."

Figure 3: Path Tracing

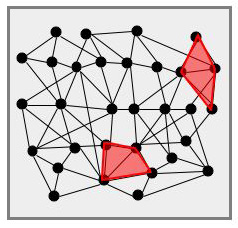

In Figure 4 two areas of the network are highlighted, each consisting of five nodes where the pattern of connection is the same in each network. Though the two subnets have different orientations and overall proportions in the 2D representation of the network, those are irrelevant; what matters is the pattern of connectivity, and that is the same in each network. Each consists of four nodes connected by five links in the same configuration. Hence the patterns match. Of course, pattern matching implies a second order network, or some other meta-structure, to recognize the match (Hays 1981).

Figure 4: Pattern Matching

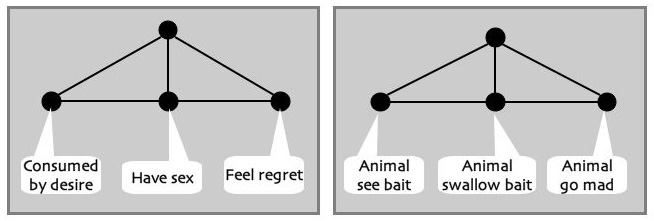

Continuing with Shakespeare’s sonnet, one of those fragments might represent the basic lust sequence at the heart of the sonnet while the other embodies the simile that is introduced in lines seven and eight: ". . . a swallow'd bait/On purpose laid to make the taker mad." Both of these actions involve a three part sequence and so the network fragments representing those sequences have the same form (see Figure 5).

Figure 5: Lust and Madness

Working in this way we could construct a relational network as the basis for the sonnet’s meaning (Benzon 1976). The meaning of the poem would then arise in the interaction between the text and such a network, where the network is implemented in someone’s mind. Such networks, of course, may differ from one individual to another and even where highly similar, may have different emotional resonance.

Thus far we have two general computational processes, path tracing and pattern matching; I believe there are at least two others. So far we have assumed that the meanings of individual lexical items combine in what I will call complementation mode. The perceptual and cognitive schemas that give meaning to the lexemes take their place "alongside" one another in a conceptual frame of some sort, but they do not interact with one another in a deep way. When the supporting schemas interact with one another in a rich way we have conceptual blending as Giles Fauconnier and Mark Turner have discussed (2002). Path tracing can support blending on a small scale while pattern matching supports blending on a larger scale. When David Hays and I (Benzon and Hays 1987) argued that strong metaphor depends on sensorimotor schemas we were, in effect, offering a neural model of at least some aspects of conceptual blending. In our view, metaphor uses the propositional power of language to "filter" one sensorimotor schema through another, with the resulting "precipitate" being an abstraction that is the emergent ground of the metaphor linking the two sensorimotor schemas.

Note that these processes of semantic meaning—path tracing and pattern matching in both complementation and blending modes—are not specific to literature. These processes apply to language in general. Specifically literary processes have to do with literary form and style. It is not clear to me that it is possible to formulate a completely general principle of literary style and form. When properly interpreted, Roman Jakobson’s (1960) well-known poetic function may well be just the thing. But I am not aware of such an interpretation. The sense of Jakobson’s function is to move the physical stuff of language, its sounds and rhythms, into the foreground or one's consciousness. I suspect that literary texts do this more thoroughly, and on more scales of organization, than do other texts. But I am not prepared either to assert or argue this point here and now; it must be considered open to further investigation. In any event, I see little need sharply to divide the world of texts into literary and non-literary texts. I am content to think of that division as a fuzzy one that depends on more or less local habits and conventions and, as such, is subject to change and revision.

Now let us connect use the idea of a network to develop the ideas of constituency and armature. Let us start with constituency. Consider Figure 6:

Figure 6: Path with Three Constituents

The diagram depicts the same path displayed in Figure 3, with is the path traced through some cognitive network as it is rendered into language. In Figure 6 the path has been broken into three segments. Each of those segments is a constituent of the entire path. Each of those segments could, in principle, be divided into constituents and, by the same token, the entire path could be a constituent in some longer path.

There is psychological evidence that the constituent structure of sentences reflects the way the mind (unconsciously) parses them for processing (Neisser 1966: 259 ff., Taylor 1976: 105 ff.). I am simply, and perhaps rashly, extending this notion to the entire text (as does Cureton 1992, pp. 179 ff.). The meaning of a text may or may not, ultimately, be a single gestalt. But the process of arriving at that meaning has a structure in which partial meanings are "computed" and, in turn, combined into more comprehensive meanings, until the entire text has been comprehended (Alvarez-Lacalle and Dorow 2006).

To develop the notion of an armature, consider Figure 7:

Figure 7: Animals Eat Food

At the top of the network we have three nodes that could be rendered into language as a simple generalization, animals eat food. Beneath the animal node we have a tree structure indicating that birds and beasts are animals, and that robins and eagles are birds while dogs and horses are beasts; obviously this is only a portion of the tree for animals. Anyone of these subordinate nodes could be substituted for animal in the assertion, "animals eat food," and the assertion would remain valid. Thus we could consider animal to be a variable while beast and bird would be specific values for that variable, and so on for robin and eagle in relation to bird and dog and horse in relation to beast. This fundamental distinction, between variable and value, is important to the notion of an armature.

Notice that the notion of food is as general as that of an animal. While robins and German shepherds do eat food, what is food for one is not necessarily food for the other. German shepherds generally don't eat worms nor do robins eat chopped liver. These are matters of empirical fact, not logical form. "Dogs eat liver" is a valid assertion while "dogs eat tofu" is not. Liver and tofu are both kinds of food but dogs eat the former, but not the latter. Once a variable has been chosen for one of the variables in a generalization—such as "animals eat food"—that choice places constraints on the values that can be chosen for the other variables. By armature I mean the generalization, such as "animals eat food," along with the constraints on animal types and food types (that is on values for the variables) required to produce valid assertions.

This is not quite how Lévi-Strauss proceeded when he introduced the term in The Raw and the Cooked (p. 199) for he was concerned with myths, not simple empirical generalizations. Where I talk of a general assertion—e.g. animals eat food— he talks of a "a pattern of functions," where his functions correspond to my variables. And where I talk of values he talks of the code. In both cases the armature consists of "a combination of properties that remain invariant" in various cases where code elements (values) have been assigned to functions (variables). In the case of simple generalizations, the proper combinations yield true statements; in the case of myths, the proper combinations yield satisfying myths. In the language of structuralist linguistics (e.g. Jakobson 1956, 1960), constituency is related to the axis of combination while armature is related to constraints on the axis of selection.

Given these various ideas about computation I offer these two closely related propositions:

3. Form: The form of a given work can be said to be a computational structure.

In this essay I will be concentrating on constituency and armature, but I do not believe that these computational notions exhaust the idea of literary form, as I have already indicated.

4. Sharability: That computational form is the same for all competent readers.

In effect the sharability proposition states that the computational structure of a work is an objective property of that work and, as such, is accessible to all qualified readers, that is, readers who have assimilated the conventions governing a particular type of text. The meaning of texts is open-ended, but their form is not.4 Most of my discussion will center on form itself, taking sharability for granted.

Constituent Structure

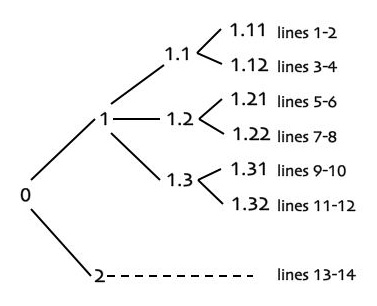

Let us begin our examination of constituency with a well-known formal pattern, the Shakespearean sonnet. In this 14-line form three quatrains are followed by a couplet, thus:

Figure 8: Structure of a Shakespearean Sonnet

The rhyme scheme is: abab cdcd efef gg. Note that this scheme reinforces the boundaries between the quatrains. Each branch of this tree indicates the "processing" of a portion of the poem. One processes section of 1.11 and obtains a partial result. Once one has processed 1.12, one can now obtain a partial result for 1.1. Sections 1.2 and 1.3 are processed in turn and, when complete, one can obtain a result for 1. One then processes the final couplet and combines that partial result with the result for the quatrains and thus arrive at the poem’s meaning. In the case of Shakespeare’s sonnet on "Th’expence of Spirit" the quatrains move back and forth through a sequence of desire, consummation, and shame and the concluding couplet brings stability and closure by admitting that all people share the emotional turmoil of that inevitable sequence (Benzon 1976, 1978, 1981, 1993a: 131-133; see Hobbs 1990: 115-130 for the analysis of a Milton sonnet).

All competent readers will parse the text in the same way; that is to say they will arrive at the same structure of partial meanings being organized into more inclusive meanings culminating in the meaning of the entire text. As I have already indicated, this process is unconscious. It is not something one does deliberately and according to explicit criteria. Where competent readers will differ is in the meanings evoked at the lowest level of this constituent structure. The important point, however, is that the varying meanings different readers bring to the words and phrases in a text are processed in a computational structure that is the same for all competent readers. The significance of this assertion will become more apparent with the discussion of hypotheses five and six below. For now, I want to return to constituent structure.

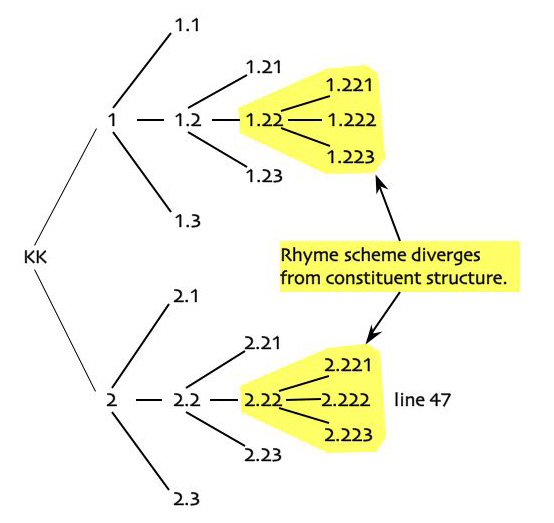

The constituent structure of fixed poetic forms, such as the sonnet or madrigal, is obvious enough; it is, in fact, defined in the form itself—which, of course, affords the poet the opportunity to work against the structure, a complication which is beyond the scope of a brief statement such as this (cf. Fish 1980, Tsur 1992, pp. 126 ff.). But constituent structure exists, of course, in poems not based on formulas that strictly govern meter, rhyme, and stanza structure, such as Coleridge’s "This Lime-Tree Bower My Prison" or "Kubla Khan." The constituent structure of "Kubla Khan" is quite elaborate, consisting of a systematic interplay of binary and ternary branchings (for details of this analysis see Benzon 1985, 2003b). The ternary branchings provide the key to the poem’s structure. The diagram below depicts those ternary branchings. I have "trimmed" the binary branchings to simplify the structure a bit; all of the terminal nodes in the following tree in fact have binary branchings except 1.221, 1.222, 1.223, 2.221, 2.222, and 2.223:

Figure 9: Constituents in "Kubla Khan"

The poem has an elaborate rhyme scheme which parallels the constituent structure quite closely, deviating from it in only two sections, 1.22 and 2.22. Notice that the deviation is at the same structural position in the two sections of the poem. In the first part of the poem that middle of the middle is where the fountain bursts into Kubla’s realm and gives birth to the river Alph. In the second part of the poem that middle of the middle consists of a single line (47), "That sunny dome! those caves of ice!" The poem’s structure thus suggests that those two elements perform a similar function in their respective contexts (cf. Roman Jakobson’s remarks on the poetic function of language, 1960). We should note that line 47 is a repetition of the line 36 ("A sunny pleasure-dome with caves of ice!"), which ends the first section of the poem and which, according to my semantic analysis, embodies the various threads of meaning at play in that section.

With respect to this particular poem, the identification of form with computation asserts that the meaning of the first section of the poem enters into the meaning of the second section at line 47. Sharability asserts that this is true for all competent readers regardless of the specific and individual associations each may have for the various words and phrases in the poem. However the sense of that pairing (the sunny dome and caves of ice) may vary from one reader to another, that the paring occurs twice in the poem, and just where it occurs, that is the same for all readers. Given the infamous history of this particular poem and its critical commentary (see Tsur 1987), these are not trivial assertions.

The more general argument, of course, is that similar assertions are true for all works of literature. My examples have been drawn from lyric poetry, but I think the principle applies to other distinct types as well. I do not, however, regard the business of "scaling" up from relatively short lyrics to full-scale dramas and narratives as a simple or obvious matter. Let me offer a few informal remarks.

One example of a large-scale formal structure is the ternary form that Northrup Frye (1965) and C. L. Barber (1959) have identified in Shakespearean comedy. As both of them knew, the form is an old one. The skeletal story is a simple one: 1) boy meets girl, 2) they are separated, 3) they are reunited. Patrick Colm Hogan (2003) has found this story in many oral and literate cultures around the world. As Shakespeare has realized the form, the whole world of the play shifts into a different mode in the separation phase. In this middle phase social structure is temporarily dissolved and it is through that dissolution that the couple can become reunited society be reconstituted around them.

Note that at this point we have gone beyond simply identifying constituent structure. We are now analyzing the relationship between different constituents. It is one thing to say that a story has three components; it is another thing to assert that, for some class of texts each having three components, the components have certain characteristics. In general, once one has identified the constituents, one then goes on to characterize the role each component plays in the complete work. I have analyzed a different kind of triple form in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight (1977). The story begins and ends in Camelot but the middle episode (the third of the text’s four divisions) takes place at Hautdesert, in the wilderness far from Camelot. Hautdesert is an anti-court. King Arthur presides at Camelot, but a woman—Arthur’s half-sister, Morgan Le Fay—presides at Hautdesert. Whereas knights pursue ladies at Camelot—Gawain was among the most gallant—ladies pursue knights at Hautdesert; Gawain is pursued by his host’s wife. The story is rich and ironic, and resists easy summary. My point is simply that it has a triple form, one that shares a critical characteristic with other stories of triple form, that the middle sequence takes place in an anti-world.

More elaborate structures, of course, are possible. One such structural type is so-called ring form (Peterson 1976, Paxson 2001), where a narrative will unfold through a series of steps to a mid-point and then trace its way back through the same series of steps, but in reverse, thus:

1 2 3 . . . X . . . 3’ 2’ 1’

Mary Douglas (1993, 1999) has been investigating ring structure in books of the Old Testament, while I have found it in Osamu Tezuka’s graphic novel, Metropolis (Benzon, in press). The fact that rings are symmetrical about a mid-point suggests that they may ultimately depend on the cognitive structures we use for use for spatial navigation. If you travel from location A to N and then back you will pass the same landmarks on each half of the journey, but in reverse order. This, of course, is no more than a raw suggestion.

Haruki Murakami’s recent novel, Kafka on the Shore, employs a different kind of formal device. The story follows two protagonists, a teenaged boy and a middle age man and is organized into 49 relatively short chapters plus a short introductory section focused on the boy. The first chapter is set in the present and is about the boy. The second chapter is in the past and is about the man. The chapters then alternate to the end of the book: boy, man, boy, man, and so on. As the story advances the two plots become intertwined into the same story. While there may well be a higher level structure at work, that is, in this context, a secondary matter. What is important is simply the use of alternating chapters as a formal device. And so it could go for who knows how many more formal devices governing constituency. The objective here is not to make an exhaustive list, but only an indicative one.

Armature

As the computational metaphor and algebraic example suggests, the notion of constituency has mathematical roots. Mathematical expressions have variables (x and y, etc.) and variables can take values (such as numbers). The elements of the armature are analogous to variables. As such, any number of elements in a literary work could be in its armature—practically anything named in word or phrase. I do not, however, believe that is the case; but I do not know how to formulate an a priori definition of armature elements. So we must proceed inductively, by considering examples.

Characters may be the most important class of armature entities. For that reason I want to begin my discussion of the armature by discussing characters. Let us start with a paragraph from Norman Holland's The Dynamics of Literary Response. Holland is preparing to argue that we are justified in treating literary characters, mere fictions, as though they we real people:

Let us turn and look in another direction, namely, Smith College where in 1944 two psychologists performed a quite fascinating experiment. To a group of undergraduates, they showed an animated cartoon detailing the adventures of a large black triangle, a small black triangle, and a circle, the three of them moving in various ways in and out of a rectangle. After the short came the main feature: the psychologists asked for comments, and the Smith girls "with great uniformity" described the big triangle as "aggressive," "pugnacious," "mean," "temperamental," "irritable," "power-loving," "possessive," "quick to take offense," and "taking advantage of his size" (it was, after all, the larger triangle). Eight per cent of the girls even went so far as to conclude that this triangle had a lower I. Q. than the other.

Those simple geometrical figures are no more representations of real people than are the subjects of a Mozart sonata. Yet the Smith students were quite comfortable discussing them as though they were human beings, just as Barlow easily treated musical subjects as human subjects. Holland’s point is that we project human fullness on to such things.

And so we do. But I want to suggest a somewhat converse notion, that on some level we experience the diverse richness and articulation of well-wrought characters as though they were simple geometric figures dancing about in space. That is to say, when we watch a Shakespeare play or read a Flaubert novel, there is a level of our understanding that apprehends the interacting characters as though they were no more elaborated than the triangles and circle of the film watched by the Smith students. I would speculate that those mechanisms are subcortical and thus intimately linked to our subcortical emotional circuitry.

Consider the "vibe" you get upon first meeting someone, that lasting first impression in which you inscribe later impressions. If I had to guess, I would guess that such appraisals are made in the portions of the limbic system (informally, i.e. the "lizard" brain) that are devoted to emotion and social cognition while our more differentiated apprehension of others is embodied in phylogenetically more recent cortical tissue. And so it would be with literary characters as well; each character has a relatively undifferentiated subcortical component that is linked to a highly articulated cortical component. The "paths" the subcortical components "trace" in "socio-emotive space" are analogous to the development of musical subjects in a composition.

I am thus asserting that we treat characters, not simply as complex ordered collections of various attributes (cf. Rimon-Kenan 1983, 29-42), but that we also treat them as integrated wholes. If this is true at all, it will be true because human beings are very astute at assessing one another and in appraising social situations, a matter that has been given considerable attention in recent thinking about human evolution (see e.g. Barkow, Cosmides, and Tooby 1992; Baron-Cohen, 1995; Boehm 1999; Allman 1999, 173-174, and Mithen 2005). I further suggest that the various manipulations considered under the heading of point of view and focalization depend on the capacity to treat characters as single units of computation. Darwinian critic Joseph Carroll (2004, 2005) has given special consideration to this in his most recent theorizing. Let me suggest this proposition:

5. Character as Computational Unit: Individual characters can be treated as unified computational units in some, but not necessarily all, literary forms.

Now we are ready to consider a specific example, Shakespeare’s Much Ado About Nothing. This comedy presents us with two very different couples, Claudio and Hero, and Beatrice and Benedick. Each couple is involved in a romance and the overall structure of the play derives from the interaction of these two plots. I suspect that competent readers "filter" (cf. my remarks about blending above) one couple’s story through the other couple’s story and arrive at a psychological problematic which is common to both couples. This is a formal possibility inherent in multiple plots and does not depend on the exact nature of the plots nor of the characters in them (cf. Empson 1974, 34).

At this point it seems to me that we are working at the level of abstraction Propp assumed when he discussed the functions of a tale’s dramatis personae. As Propp observed, "the number of functions is extremely small, while the number of personages is extremely large" (Propp 1968, p. 20). The configuration of functions realized in a particular story is a formal matter, while the details of the characters occupying those functions belongs to the story’s content. The Shakespearean double plot involves a certain configuration of functions; these functions are formal elements in the computational structure of the story-form.

One issue that has come up in commentary on Much Ado concerns Claudio’s character: Is he a true romantic, deeply in love with Hero, or is he an opportunist on the lookout for an eligible heiress? Critics favoring these positions (or variants of them) argue in the standard way, quoting passages to substantiate their views on the matter. Both views thus have textual authorization. I would like to suggest that this particular argument is of little consequence.

I make this suggestion, not because I am indifferent to the conflict between these two readings of Claudio’s character—though one might well argue that, just as real people are not thoroughly consistent, neither are literary characters—or even because I wish to allow different readers their own readings, though I do wish to allow that. I have something different in mind. It seems to me that what is central to this play, as with the subjects of a sonata, is formal contrast. In the play we contrast the two relationships and the individuals in those relationships: Claudio and Hero, Beatrice and Benedick. It is the contrast between Claudio and Benedick that is important, not the exact formulation of either one’s character. Whatever Claudio’s motivation, he interacts with Hero in a way that is quite different from the way Benedick interacts with Beatrice. The relationship between Claudio and Hero is asymmetrical; he talks and pursues while she says little and consents to his suit. The relationship between Beatrice and Benedick is symmetrical; they both talk, a lot, and there is no conventional male pursuit of his beloved. The contrast between these two sets of lovers is, I submit, more robust than their individual natures considered in isolation. That contrast is central to the play and it is, in the sense that I am arguing, a formal matter. That contrast is between characters in the play’s armature.

My next proposition is a generalization of that observation:

6. Armature Invariance: The relationships between the entities in the armature of a literary work are the same for all readers.

Whether or not that proposition is true, what it means is clear enough in the case of characters. To take another example, however readers may disagree about Hamlet’s nature, the relationship between Hamlet and Ophelia, Hamlet and Gertrude, Hamlet and Claudius, and so forth. But what does this mean for other kinds of entities, and just what other kinds of entities might be in the armature?

Let us consider a recent movie: the recent remake of King Kong. The armature of such a story certainly includes the main characters, such as Kong, the actress Ann Darrow, the movie director, the boat captain, and few others. But it may also include places, e.g. New York and Skull Island. There is a moment somewhere in the middle of the film when Kong and Ann are resting in his nest on Skull Island, high up on the mountain. It is early evening and we see them interacting against the sunset in the background. This moment had been preceded by a great deal of strenuous action and violence. There is a similar moment near the end of the film. In this moment Kong is atop the Empire State building and is wounded from having been shot several times by machine guns mounted in airplanes. He had carried Ann here as we was running from his captors. Again, a great deal of violence has preceded this moment. But, for this moment, the planes have stopped shooting at Kong and he is resting, with Ann sitting in his hand. It is evening, and the sun lights the sky behind them, just as it had back in his mountain nest.

Whatever any given movie-goer feels in these moments, whatever they think they mean, the parallel is there for everyone to see. I am suggesting that even such incidents, akin to Propp’s functions, are components of the armature as well. Whatever feelings these scenes may evoke in viewers, the relationship between the two scenes is fixed for all viewers. That relationship is fixed by the movie itself, the relative ordering between them, the exact time between them, the preceding and succeeding sounds and images, those are all fixed.

Beyond this, it is not obvious to me how one would provide a general and a priori characterization of the entities that constitute the armature of a text. I have talked about the major characters in a narrator, and about specific episodes. Are minor characters part of the armature? What of the many characters in, e.g. War and Peace: are all of them in the armature? The answer is not immediately obvious, nor is it particularly pressing.

Lyric poetry presents more pressing issues. Here there is only one speaking character, the poet or poetic voice, though there may be one or more characters addressed or spoken about. In any event, the burden of the work is variously on what is seen, thought, felt, or desired. Consider, once again, Shakespeare’s sonnet 129. How many characters do we have here? Certainly there is the rather abstractly conceived person consumed and troubled by lust. Is "the world" that "well knows" this story to be considered a separate character? Regardless of the answer, I also believe that the stations of lust (recall Figure 5) are in this poem’s armature. The order in which they are evoked is necessarily the same for all readers.

As another example, recall "Kubla Khan." Kubla and the wailing woman are in the armature, as are the ancestors, all in the first movement. In the second movement we have the poet, the damsel with a dulcimer, and the auditors who cry "Beware!" Beyond that, I have already noted that lines 36 and 47 are almost exactly the same, and have asserted that the poem’s structure fixes the relationship between those lines for all readers. But we could also consider simply the caves of ice, on the one hand, and the sunny pleasure-dome on the other. They are significant entities in that poem and I would expect that the relationship between them is the same for all readers, through each reader might well have his or her own sense of them. The poem has other significant entities as well, including the fountain, the river Alph, the music loud and long, and so forth.

As a still different example, consider William Carlos Williams’s "To a Solitary Disciple," the poem Lakoff and Turner used as their central example in More Than Cool Reason. We have the poetic voice, an addressee mentioned only once—"mon cher" in the first line—and a series of admonitions from the first to the second—observe, notice, grasp, see, etc. -- and two central objects, the moon and the church steeple. The moon and the steeple are surely armature entities, but the poet and his disciple? What of the colors—pink, turquoise, orange, etc.—so important in the poem? The answers to these questions are not clear. Other than the steeple and the moon, it is not clear that these entities play the signal role in this poem that characters play in a narrative.

Perhaps the notion of an armature is not so useful for such poems, either because it captures too little or even because it might be forced to capture too much. I can see no way to puzzle through the issue except to consider specific examples in some detail. That is beyond the scope of this essay. If the notion of an armature is useful for a large set of literary works, that is all I ask of it. A generalization need not be all encompassing if it is to be useful.

An Empirical Note

It is fine and dandy to assert, as I have done, that relationships between the entities in the armature of a literary work are the same for all readers. I have even provided some argumentation in one specific case, Much Ado About Nothing. But how could we get empirical evidence on the matter?

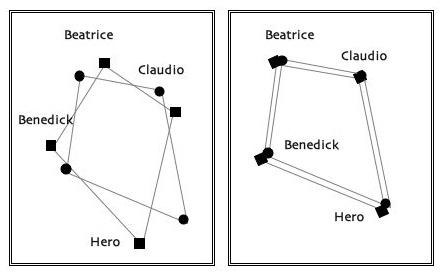

While I certainly do not have a general approach to offer, nor do I know of any empirical work that speaks to the problem, I have a suggestion about how we could begin gathering evidence. Let us consider the case of literary characters and continue with Much Ado as an example.

I think the five-factor personality model could be used to gather relevant evidence. This model conceives of personality as have five factors: Extraversion, Agreeableness, Conscientiousness, Emotional Stability, and Openness to Experience (cf. Carroll 2004). Mathematically, each of five factors corresponds to a dimension in an abstract personality space—perhaps this is the perceptual space of our neural equipment for social cognition. A subject completes a test instrument and, on the basis of his or her responses, is assigned a value on each of the five factors. Thus the nature of one’s personality is characterized by a point in a five-dimensional space. While the commonest use of the model is for individuals to appraise themselves using an appropriate test instrument, it is also possible to use test instruments to appraise the personalities of others (Funder 1999). I have been assured by experts (David Funder and Joseph Glickstein, personal communication) that it would be possible to evaluate the personalities of fictional characters.

To test my hypothesis about characters in Much Ado we would have subjects read the play or watch a performance of it. Once they are done, let them rate each of the four central characters using a five-factors test instrument. Thus, for each test subject we will end up with four points in the five-dimensional space defined by the five factors; each point indicates the personality of one of the central characters in the play: Beatrice, Benedick, Claudio, or Hero. Four points determine a quadrilateral. So let us now compare the quadrilaterals generated by each subject’s response as measured by a five-factors inventory. My hypothesis is that, while the quadrilaterals may vary among the subjects in position and orientation within the space, they will be congruent with one another. That is, the corresponding sides will have the same lengths and the corresponding angles will be the same as well.

Figure 10: Characters in Abstract Personality Space

Figure 10 illustrates the general principle; though that space is only 2-dimensional, the principle holds for spaces of higher dimensionality. On the left we see two sets of points indicating the personality judgments of two hypothetical subjects; the judgment of one subject is represented by round points, the other by square points. Since the corresponding points for these two subjects are in different locations, it is clear that these two subjects differ in how they assess the personality of each of the characters. Now look at the right, where one set of judgments (square points) has been rotated counter clockwise so that we can more readily compare the two sets. We see that the quadrilaterals are congruent, indicating that both subjects regard the relationships between the characters as the same.

Obviously this particular mode of empirical investigation will not work where we have armature entities that are not people. It would not be appropriate if we wanted to gauge the relationships among fountain, dome, and caves in "Kubla Khan." We might, however, try asking subjects to think of those things as though they were people and then to ascribe personality characteristics to them—recall the Smith experiment that Holland reports.

More directly, we could use a different text instrument. Psychometricians have many other them; perhaps the venerable semantic differential (Osgood, May and Miron 1975) would produce useful results. Whatever the test instrument, I do not, in principle, see any problem with conducting such measurements.Forms and Formalism

However important constituency and armature are, they are not the only formal aspects of literary works, as I have remarked before. Returning to Shakespeare, for example, he uses distinctly different kinds of language -- blank verse, rhymed verse, prose, etc. -- for different dramatic purposes. That too is a matter of literary form, as are the various strategies of the narrative voice in novels. Other phenomena are relevant, many discussed under the rubric of narratology (Genette 1980, 1988), but these examples are enough to suggest that there is more to literary form than constituent structure and poetic sound patterning. A naturalist criticism will need to reconceptualize traditional discussions of these forms using computationally informed strategies. Reuven Tsur’s Toward a Theory of Cognitive Poetics, conceived under the aegis of Gestalt psychology, catalogues and illustrates many formal devices, and brings them within the scope of the contemporary cognitive sciences.