The depiction of the house in the free drawings of Haitian street children: Dreaming of and recreating a habitat.

by

Amira Karray ,

others

,

others

March 7, 2015

The aim of this article is to analyse the spontaneous drawings of houses produced by 45 street children in Haiti after the earthquake of 12 January 2010. The drawings were made during workshops held in children’s homes and child reception centres. Given that over half of the random sample free drawings (n= 270), depicted houses, questions were raised in our minds about the expressive and projective value of drawings of houses for children deprived of such homes. We also sought to explore the symbolic and creative value of the act of drawing itself. Based on the theories of Winnicott (1975, 1984) and Anzieu (1984), analysis of the 161 drawings produced revealed that these street children seek a sense of inclusivity and healing for the envelopes weakened by their experience on the streets, alongside a desire for familial bonds and support, and a narcissistic fragility. However, the analysis also revealed evidence of a set of potentially creative resources – a targeted and contextualised capacity for expression; a quest for socialisation and interpersonal skills; an ability to ‘compensate’ for failure through attempts to construct. Drawing as a creative activity and play area, thus appears to represent a model of artistic activity with the potential to be a resilience factor.

The depiction of the house in the free drawings of Haitian street children

Dreaming of and recreating a habitat

Amira Karray, Daniel Derivois, Jean-Pierre Durif-Varembont, Eric Jacquet, Iris Wexler Buzaglo & Helen Marchal.

University of Lyon

Author note

Amira KARRAY, PhD, psychologist

Daniel DERIVOIS, PhD, Associate professor, psychologist

Jean-Pierre DURIF-VAREMBONT, PhD, Associate professor, psychologist

Eric JACQUET, PhD, Lecturer, psychologist

Iris WEXLER BUZAGLO, PhD student

Helen MARCHAL, Student

Correspondance concerning this article should be adressed to Amira Karray.

The depiction of the house in the free drawings of Haitian street children

Dreaming of and recreating a habitat

This paper focuses on children and teenagers from the streets of Haiti, in the post-earthquake context, through the mediation of free drawing. While the issue of street children is not a new phenomenon, it has become a greater preoccupation since the earthquake of 12 January 2010, with the increase in numbers of street children, and the growing challenges of living on the streets. These children both inhabit and occupy the streets. They live in groups, moving around, surviving and frequently changing places… From time to time, as a result of random meetings and movements, they are taken in or accommodated in children’s homes, before returning – more often than not – onto the streets.

Through the drawings of houses, freely produced by children and teenagers encountered in the context of the research project Résilience et Processus Créateur chez les Enfants et Adolescents Haïtiens Victimes de Catastrophes Naturelles[1] (RECREAHVI, ANR-10-HAIT-002), we examine the concerns of these young people and their ways of depicting their traumatic lives as well as inhabiting both their bodies and – for want of a home – the streets. We also investigate the creative capacities of these children in terms of the construction of a house – a home of their own that they have lost but continue to seek.

In this paper we attempt to analyse the drawings of houses by street children as a representations/projections of an inhabited or potentially inhabited place, of a sought-after house and its symbolic role (Eiguer, 2004). The house drawing is also considered in its projective capacity as a projection of the child’s own body as well as that of the family (Cuynet, 2010). Moreover, the house drawings also help shed light on the dynamic between the indoor and outdoor worlds, in which the characteristics of the walls of each house offer an insight into the quality of the subjects’ psychic envelopes (Anzieu, 1984). More broadly, the drawing of a house – in particular when it is produced without specific instructions as a form of free drawing – offers us a way of understanding the emotions, (Picard & Baldy, 2012) and apprehending the markings made by the child himself and addressed to others (Vinay, 2014).

Drawing gives the child a means of expressing and setting down their concerns and offers a glimpse in the case of street children of traces of the traumatic past (individual and collective trauma as well as the possibility of psychological and intersubjective healing, support and construction. The drawing paper thus becomes an intermediary space (Winnicott, 1965, 1971) where the child projects and transforms aspects of their inner world and outer environment. Drawing thus becomes a means, a mediator, for relating to the outer world, while engaging a number of internal psychological processes (Vinay, 2014). It is, therefore, a creative act.

Creative processes lie at the heart of child development, whether emotional or cognitive. They emerge in any activity where a playspace becomes possible (Winnicott, 1971). It is this playspace that becomes, for the child, a place of bonding and identification of the successive losses inherent to development. This playspace and the processes it involves requires a sound and secure environment. In situations of deprivation, deficiency, or trauma, this environment is often missing – at least for a time – thus hampering the possibility of playing/bonding and creativity (Winnicott, 1984). However, paradoxically in these situations, creativity offers an ideal and feasible path towards repair and access to pleasurable experiences (Nicholson, Irwin & Dwivedi, 2010).

This paper examines the creative process in Haitian street children through their drawings of houses. This subject can potentially show both what the children are missing while living on the streets and express the desires and defence and creative mechanisms they deploy in order to compensate for these deficiencies and dream of another environment. It therefore explores these children’s capacity to create a structured inner world while at the same time structuring their potential resilience. These are studied in terms of their internal aspects linked to the creative process and the reliability of internal objects, as well as the external aspects, linked to the possibility of harnessing the real environmental resources in the context of the streets.

We therefore focus on the drawings of houses in terms of what they say about inclusion, and the springboard they offer for self-projection, reflecting the quality of the narcissistic foundations, as well as a canvas for projection of the family unit and for bonding with the external environment.

Method

The methodology involved a series of drawing workshops for 45 children and adolescents aged between 10 and 18 in three different institutions in Port-au-Prince. In every institution, the workshops took place three times a week for a period of three weeks (total = 9 sessions per institution). Participation in the workshops was free and the only instruction given to the children was to create a free drawing. Blank paper and pencils were made available. The sessions, led by a trainee psychologist and a facilitator, lasted 90 minutes and the children were allowed to make several drawings within a single session. This methodology produced over 600 drawings for our collection. This paper seeks to analyse a sample of 270 drawings randomly selected.

Although the children were asked to produce free drawings, we noted that several children spontaneously drew houses – and did so over several consecutive sessions. Based on our observation of the characteristics of the houses in the sampled drawings, our analysis focuses on five criteria:

1. The prevalence of houses in the overall sample

2. The quality of the walls of the houses (envelopes)

3. The richness and detail of the houses (narcissistic aspects/aesthetic quality/investment/movement)

4. The existence of family life in the house and the quality of family ties

5. The existence of an external environment and the quality of that environment

Results

The prevalence of houses in the overall sample

We used 161 drawings of houses out of a total 270 drawings on the same theme produced in the free drawing workshops – a prevalence of 59.6% of the spontaneous drawings of houses. This first observation is in itself interesting, as free drawing promotes instinctive and emotional expression, unconscious tendencies and the notion of targeted communication (Vinay, 2014). The frequency of house drawings, in a context where instructions were deliberately lacking (no guidelines were given concerning content) can be understood as the expression of the need for a context that offers inclusion and structure. Just as the children lack a house on the streets, they seem to transpose this experience into the drawing workshops and thus doubly underline this deficiency, this need and desire for a house – the need and desire for inclusion.

Seem from this perspective, the house drawing is an attempt par excellence to give expression to something that is missing, and desired, in a way that is addressed to others. Given that the drawings were produced in a collective context, we may also presuppose a collective element to this addressing of the same problem, the same preoccupation, but also the possibility of a shared experience, a non-dangerous experience of intersubjectivity (Hagman, 2000) which is sure to be received and heard.

The quality of the walls/envelopes of the house

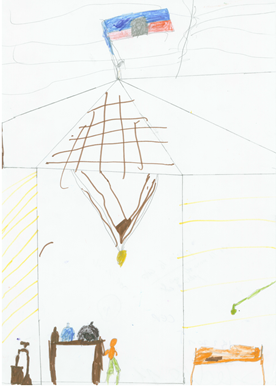

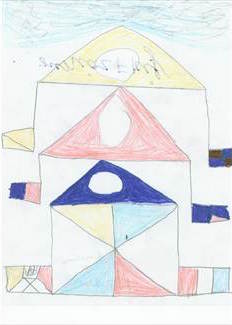

Most of the houses feature rigorous and carefully delineated geometric forms (drawings 1, 4, 5). The external contours of the houses are extremely emphatic, with forceful lines drawn time and time again. These lines demonstrate the need to separate the inner from the outer, to differentiate between these spaces and to create an internal space for oneself that is both real and psychological.

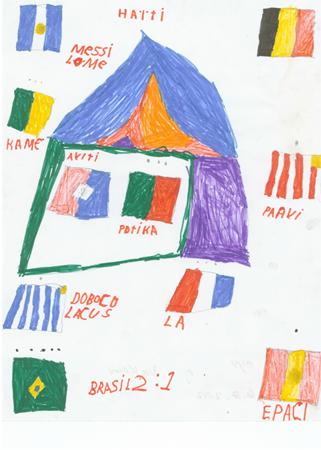

However, despite these strong lines, the houses give the impression of being embedded in the environment that surrounds them, without distance. As if they represented a continuity of the environment against which the carefully drawn line alone provides a contrast (drawings 1, 2, 3, 4). This creates compact drawings, in which the houses are separate from the environment but the same time encased within it.

The rigidity and opacity of the walls in the drawings also reveal a fear of collapse and the need to structure – through lines and geometric shapes – a personal and individual space sheltered from the eyes of others. This seems to denote a need for protection, in contrast with the children’s lived experience in which they are exposed both physically and psychologically to the hazards of the environment, the gaze of others, noise, etc. In fact, in these drawings of houses, we see very few openings (windows, doors), (drawings 1, 2, 3, 4, 5).

However, another type of house exists – albeit rare within the sample (N=7), which includes a number of openings and walls that are much thinner, even creating an impression of transparency or of dynamism between the inner and the outer, and of psychological vitality (drawings 6, 7, 8). We will address this type of house in the fourth section of the results (family life in the houses).

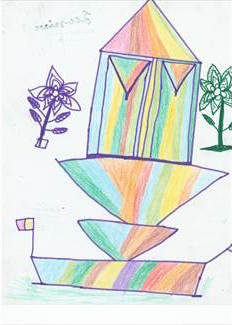

The richness and details of the house (narcissistic aspects/aesthetic quality/investment/movement)

Seen as a whole, the drawings of the houses display a number of signs of considerable narcissistic investment. For the most part, the drawings, in which great attention is accorded to aesthetic elements, are not only symmetrical but feature a number of multiple symmetrical effects and mirror elements. These effects sometimes undermine the fixed character of the houses, in particular in the case of ‘houseboats’ (drawings 10, 11, 12). Some of them are drawn on the basis of several parallel symmetries that endow them with a sense of movement imbued with a precarious and shifting balance, thus enabling them to be seen as houses, whatever the observer’s point of view (we also see a house or a boat if we turn the sheet upside down, cf. drawings 4 and 12). The symmetrical elements are invested, both in order to contain and structure the houses but also as aesthetic elements.

The absence of ‘real’ details in the house drawings, such as windows and doors, etc., is compensated for by ‘personalised’ aesthetic details, such as combinations of colours, artistic. Religious or national symbols: the Haitian flag, the flags of foreign countries, Vodou symbols, abbreviations or signs connected with musical movements, floral decoration, etc. (drawings 6, 7, 8, 9). These elements reinforce the idea of the house drawing as the projection of an internal space, where preoccupations and desires are foregrounded (drawings 6 and 9). These children are seeking out stable and secure identitarian bearings, as if, for lack of representations of family ties, or in order to represent these failed or deficient family ties, these children need to locate their habitat in an inclusive collective environment that symbolises their identity. Living in a house in their country, living in a protective house.

The existence of family life in the house and the quality of family ties

154 of the 161 drawings represent uninhabited houses. These ‘block’ houses represent immutable landmarks, occupying their place in the environment (drawings 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 11, 12). The majority are imposing, as if their very existence sufficed to communicate a message of distress. The need is expressed here for a solid house, which we translate as the need for a solid protective environment, not at risk of crumbling from one moment to the next. This evokes a rigid and yet fragile balance, an ‘abstract’ house – carefully portrayed but fixed and silent. Is it unreal? Inaccessible? Or incredible? It is as if these drawings are saying ‘It doesn’t matter what’s on the inside as long as I have house!’

We noticed a number of particular aspects about the seven drawings of inhabited houses (drawings 6, 7, 8). For a start, these are the only ‘inhabited’ houses. Through the transparent walls, family life can be seen continuing inside, with daily scenes which perhaps offer sufficient security to allow a certain ‘relaxation’ when the walls are drawn. For these children, a view from the outside on what is happening inside is possible, even desirable. Furthermore, at stake here is their own possible view – a fantasy of an internal world in which bonds exist and, whether deliberately or not, suggests a dream of family life.

The existence of an external environment and the quality of that environment

In most of the drawings, the houses are surrounded by a real environment, but separated from it by rigid walls. The surrounding scenes are more lively, dynamic, eventful, sometimes marked by hostility, an atmosphere of violence or insecurity (people arguing, arms, threatening animals, etc.), (drawings 1, 2, 3, 6, 7) thus confirming the protective value of the sought-after house.

These environments around the house also depict elements of the reality lived by these children in the street: a sociability accompanied by fears and intense anxieties but also by defence mechanisms constructed and interpersonal skills developed by these young people (outside scenes, dialogues, negotiations, self-expression and the expression of personal positions.).

The existence of this environment shows the possibility of ties, and the richness of social life even where this is unstructured, and a certain psychological vitality, albeit marked by great vigilance and a search for external references. What is inaccessible in and by the house is sought in a state of distress, out on the streets.

Discussion

The lost home and the experience of wandering

The drawings of houses produced by street children reveal the extent to which children and adolescents feel the need for a supportive and structuring environment. Time and again in the drawings of block houses, closed to the outside world, these children emphasise their need for a physical and symbolic structure that is lost and scattered in streetlife. This tendency to gather together, which finds expression in the solid form of the houses, appears as an attempt to recover lost objects, and beyond that an experience of lost unity. This leads us to consider the wandering life of these children as a life characterised by dispersal and, spatial, temporal and psychological discontinuity, which threatens their sense of existence.

Almost impossible to capture in direct words and symbols, the experience of loss is met with resistance in order to face up to reality and stay solid, characterised in the drawings of these imposing houses. Meanwhile, those few drawings featuring houses ‘open’ to the outside world offer a glimpse of the children’s capacity to express what is missing, as if appealing to the environment to support them.

The dream house

The houses drawn also appear as idealised, dream houses – places of healing. Through the search for narcissistic consolidation expressed by the large dimensions, the colours and the aesthetic elements, the very act of drawing takes the children into the heart of a process of creating the ideal houses – houses that could potentially meet their needs. This also involves anchoring the drawing by means of imposing, laboured shapes, and the significant addition of detail which – beyond its aesthetic qualities – seems to relate more to the marking of each child’s own traces (Hagman, 2000).

This is also a dream house in the way it differentiates spaces and structures the link with the outside world. Analysis of the drawings reveals their attempts to control and master the limits of the living space, which these children and adolescents cannot control in their reality. They therefore flag up, limit and emphasise the lines separating the spaces.

Creativity as a way of healing gaps in the inner and outer habitat

The spontaneous drawings of street children reveal how the very act of drawing enables these children to articulate what they lack and what they desire in one and the same composition. The drawing thus acts as a support for depicting what has been destroyed, lost or deconstructed, as well as support for representing what could constitute a reassuring landmark. Each series of drawings and indeed each individual drawing can combine traces of a traumatic past and – based on these very traces – represent the blueprint for a new, palliative, defensive or creative act of construction.

Just as they do in their streetlife, these children therefore deploy strategies that compensate for a deficiency, using that very deficiency as a starting point for creativity, adding and throwing together objects, times and places of life/survival which thus become part of their inner habitat (Eiguer, 2004). This is part of the creative process, as a means of dynamic construction/expression, but also part of the development of the capacity to listen and communicate one’s own emotions (Relay, 2012). This leads us to conclude that these drawings prove the potential capacity of these young people to ‘cobble together’ their habitat as their daily life in the streets continues and through their potentially traumatising experience.

Conclusion

These spontaneous drawings of houses produced by Haitian street children and adolescents offer us a glimpse into the way that they cope with the absence of inclusion and family life. They also reveal their capacity to ‘cobble together’ their inner habitat which – although precarious and characterised by a fundamental void, seems to offer a way of ‘facing up to’ the conditions of life on the street, in the light of the absence of secure ties and a reliable and stable environment. The drawing activity helped us understand this creative capacity in the young people, who used their drawing paper to show both their capacity to create and to dream amid the turmoil of their daily life on the streets.

Consequently, drawing and by extension any special artistic activity, could become a means of support for psychological and mental health for street children (McNiff, 2014), as a mechanism for expression and (re)building. It is also undeniably a way of valuing these young people, acting as a sort of mirror, enabling them to become aware of their own adaptive and creative resources.

Drawing 1.

Drawing 2.

Drawing 3.

Drawing 4.

Drawing 5.

Drawing 6.

Drawing 7.

Drawing 8.

Drawing 9.

Drawing 10.

Drawing 11.

Drawing 12.

Acknowledgements

This paper received the financial support of the ANR (French National Research Agency) -RECREAHVI, ANR-10-HAIT-002.

References

Anzieu D. (1984). Les enveloppes psychiques. Paris : Dunod.

Cuynet, P. (2010). Lecture psychanalytique du corps familial. Le divan familial, 2 (25), 11-30.

Eiguer A. (2004). L’inconscient de la maison. Paris : Dunod.

Hagman, G. (2000). The creative process. Progression in self-psychology. How responsible should we be, 16 (1), 277-298.

McNiff, S. (2014). Developing art and health. Within Creative arts therapy or separately ? Journal of applied art & health, 4 (3), 345-353.

Nicholson, Ch., Irwin, M. & Dwivedi, K-N. (2010). Children and adolescent trauma. Creative and therapeutic approches. Jessica Kingsley.

Picard, D. & Baldy, R. (2012). Le dessin de l’enfant et son usage dans la pratique psychologique. Développements, 1, (10), 45-60.

Relay, M. (2012). How creative process imact on emotional welbeing. Horizon, 59, 16-19.

Vinay, A. (2014). Le dessin dans l’examen psychologique de l’enfant. Paris : Dunod, (2nd Ed).

Winnicott DW. (1984). Deprivation and delinquency. London : Tavistock.

Winnicott DW. (1971). Playing and reality. London : Routledge.

Winnicott DW. (1965). The maturational process and the facilitating environment : studies in the thories of emotional development. New York : Internation UP Inc.

[1] Resilience and the Creative Process in Haitian Children and Adolescents who are Victims of Natural Disasters

Received: January 9, 2015, Published: March 7, 2015. Copyright © 2015 Amira Karray and others