Three Austrian Filmmakers. A psychoanalytic view on works of Kurt Kren, Peter Tscherkassky and Martin Arnold.

by

Andreas Fraunberger

December 31, 2008

I present the works of three central figures of the Austrian avant-garde film movement. The works of these figures will be analyzed from the perspective of the possibility of expression of the unconscious mind in the film medium. Hence, the main point of this project is the application of the metapsychological model of Freudian theory and subsequent theories to the film theory.

Author: Andreas Fraunberger

Translation: Mehrdad Fahramand

In the following, I would like to present the works of three central figures of the Austrian avant-garde film movement. The works of these authors will be analyzed from the perspective of the possibility of expression of the unconscious mind in the film medium. Hence, the main point of this project is the application of the metapsychological model of Freudian theory and subsequent theories to the film theory.

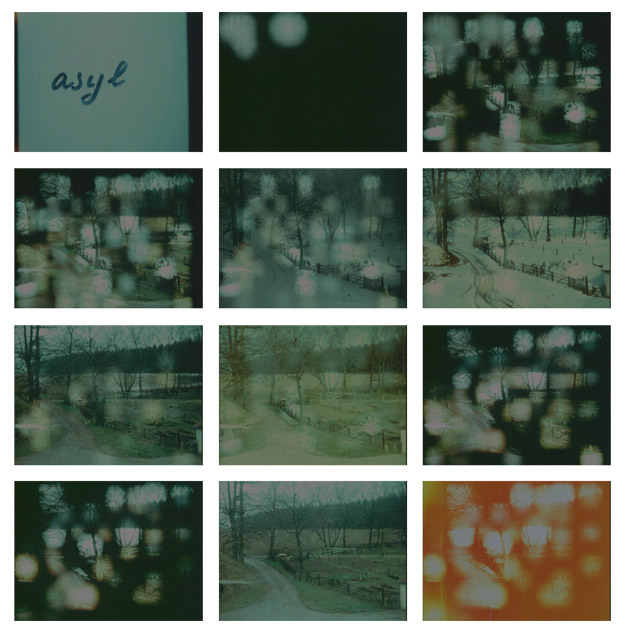

Kurt Kren and the formalism of the absurd

Kurt Kren is one of the central figures of the avant-garde film movement. He represents a radical, and contentious, artistic approach. His works are characterized by precision as well as an unbending devotion to his ideals. Kren’s experimental documentaries about Viennese Actionism go beyond simple pleasentries. Out of this confrontation emerged novel structural films, which would become harbinger for a new way of movie making. The illegalization of the works of Viennese Actionism in Austria made the continuation of any artistic work practically impossible. The course of these events led to emigration of Kurt Kren from Austria to Germany before he permanently resided in the United States. The works of Kren from this point on are characterized by a certain conceptualism. The work 31/75 Asyl was created during a stay in Saarland, where Kren visited the movie critics Charlotte and Hans-Peter Kochenrath. This film is considered as one of the main representatives of structural film. It consists of a single angle and take. In 21 consecutive days the camera captures pictures, which are filtered through a black mask installed in front of the camera with variable number of holes. On each day different parts of the film picture are illuminated. Peter Weibel coins this methodology ‘temporally extended multiple lighting’. As a result, each illumination captures only a small surface. This methodology expresses the temporally oriented visions of Kren. The Film was made in late autumn. Consequently, the pictures can be distinguished by weather changes. In some pictures we can identify a brown summerhouse and in some others the fallen snow on the ground. This technique enables a partial temporal differentiation of each frame. Through a static take a view out of the kitchen window is presented: a road, a fence, trees, and clouds. The different temporal frames which remind on an objet trouvé allow the emergence of a time-sculpture. The chronological Order of objects in a frame is reorganized through modeling within the movie length of 8 minutes and 26 seconds.

The ‘multiple illuminations’ process of the mix-photography of Francis Galton represents, from the Freudian perspective, an instance of primary function of condensation. Freud’s main interest was the cognitive processes of the unconscious mind. From the onset of the psychoanalytic movement there was a close relationship between the role of metaphors in the manifestation of mental processes and film. In the Interpretation of dreams Freud explains the process of condensation through theprinciples of composite photographs.

The face that I see in my dream is at once that of my friend R. and that of my uncle. It is like one of those composite photographs of Galton’s; in order to emphasize family resemblances Galton had several faces photographed on the same plate. (Sigmund Freud: S.E. Vol. 4, 135)

Kurt Kren: 31/75 Asyl

For instance, the beard of the uncle functions as frame for the head of the friend.

Freud explains the mechanism of dream by the analogy of Galtons phototography. Thorston Lorenz indicates this process is based on forensic picture identification (Thorsten Lorenz 1987: 108). In 1883 Sir Francis Galton developed a mix-photography techniques, in which the pictures of up to hundred subjects, such as criminals, soldiers, or patients, were illuminated on a single negative. The goal of this project was to identify common features, which could reliably indicate criminal tendencies through analysis of physical features. Here, the common features are spotlighted, while the differentiating features are relegated to the background.

Freud was interested in the relationship of presenting common features from different pictures to the condensing function of the unconscious. The point that Freud is a protégé of the cinematographic process presents an important realization for my project. The content of the optical condensation process represents a historical-structural kinship to the Freudian model of the unconscious, where the former can be derived from the latter. To this end, I will rely on meta-psychological principles to analyze the film-photographic works. In 31/75 Asyl one could also recognize the commonalities of various frames, which are informed by the condensed pictures of the unconscious. This film simulates the unconscious order of the mind at two levels, as Freud postulated it. At the first level, the setting of the film represent the topic model of the mind and hence the ‘censor’. This is illustrated through the movie medium, where a mask is inserted in between the theme and the recording material. This mask allows for the manifestation of only certain parts. This characteristic of the mask simulates the function of the censor, since here only parts of the present impressions, or past wishes, are permitted to reach the preconscious/unconscious system. Furthermore, condensation occurs at the level of censor as well, according to Freud. What the censor allows to emerge from the unconscious system will be available to our consciousness. The condensation of various temporal units represents the second level of the representation of unconscious mind within the technical setting of 31/75 Asyl. Condensation coordinates memories and desires of various temporal origins and proceeds to reorganize them in a new manner. The masked, or censored, parts in Kren’s work are of different temporal origins. However, they are put together like pieces of a puzzle generate a condensed time-sculpture. However in contrast to dreams, the material of condensation are not the impressions of a whole life lived, such as processing of the secrets of the previous day. Kren consciously chooses forms which summarize the impressions of the same theme in 21 successive days. The point of this is to relay a notion in a compressed manner. Through this, it becomes possible to simulate through the film media, and technique, the temporal functioning of the unconscious along with the process of condensation. For a painter, the fleeting and not directly presentable moments are fascinating. A filmmaker, in contrast, has from the onset the moment and the temporal montage at his disposal. Jacques Aumont writes on this difference: the filmmaker seeks “simply the ineffable, which is subject to a cumulative and hence a contradictory temporality as if it has lost the most obvious quality of time: its passage” (Jacques Aumont 2003: 22). The same essential quality of time is also missing in the primary process of condensation: the unconscious representations are rooted in past experiences. Instincts and representations, which have various temporal origins, are dragged into the present in a way that undermines their very temporal order and differentiation. In place of a linear sensory-motor time perception, this process generates through the media of pictures a direct connection between time and thinking. The aesthetics of Kren, therefore, invades a level of reflection, in which our sensory-motor capabilities are required to contemplate that which has been seen. According to Deleuze, this would be the result of a process of crystallization of time: The time is broken into crystal pieces and the movie presents on the screen the consequence of this break. Parts of the pictures remain un-illuminated and descend into darkness.

The incomplete presentation of the theme reminds us on the fragmentary testimony of persons in everyday situations as well as in clinical-therapeutic settings. The contents of the unconscious are processed at the same level of reality as the content of the manifested text, according to Laplanche/Pontalis (Jean Laplanche 1999: 224). Kren simulates this dynamic relationship in his films. Every ‘gap’ is variously illuminated, through which the temporal order thereof can be presented only partially: In the frames of 31/75, for instance, the presence of snow can be an indication of temporal differentiation of winter from the autumn as reflected by characteristic tree colors. However, the majority of frames are not temporally differentiable. Whether the pictures are of the past or the present is not determinable. The observer is required to supplement the missing information with the given features. 31/75 Asyl, consequently, represents the Freudian characteristics of the unconscious: the pictorial representation, the primary process of condensation and novel arrangement of temporality and themes.

Peter Tscherkassky – The cinematography of the psyche.

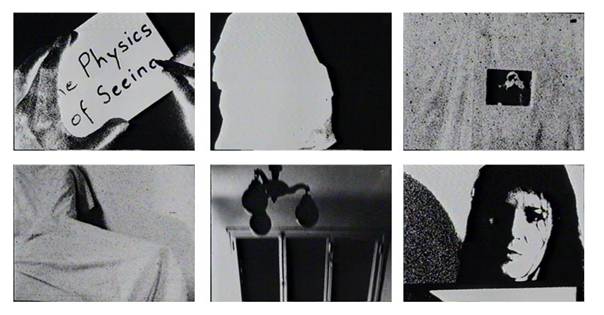

The multifaceted works of Peter Tscherkasky are characterized, since his first work at the beginning of the 1980s, by a continuous transformation. This process of change can be best noted in ‘Tilogie’ (L’Arrivee, 1998; Outer Space, 1999; Dream Works, 2001), which received worldwide acclaim. His Śuvre awakes the interest of this project due to the artist’s direct critical dealing, both in his films as well as his texts, with respect to film theory and history. His short films are characterized by a focus on the relationship of the Ego, desires, and the material, which comprise the typical subject matter of the psychoanalytic theory. That is also the reason why Tscherkasky’s Śuvre provides an appropriate platform for the analysis of the presentation of the unconscious in the Avant-garde film. In the film Parallel Space: Inter View (1992), which is the subject of my analysis, is the relationship of film and psychoanalysis unpacked. Parallel Space: Inter View leads us through a regressive temporal journey of the inner psyche by mirror pictures, psychoanalytic symbols such as the couch and the chair as locale for the memory of dialog, parental bonding, and baby or youth pictures. The accompanying text indicates to the audience the conceptual intention of the film and a view of the scrutinizing of the subject’s constitution through the given medium: ‘The Physics of Seeing’ and ‘The Physics of Memory’. The production of this work, in which partially very personal themes are dealt with, lasted more than four years. During this time Tscherkasky underwent psychoanalysis, the theme of which are presented in some of the sequences within the context of this experience. On the computer appears the script ‘all I remember…I was looking for you’ followed by pictures of a Fauteuil and a couch, which are at beginning abstract and gain in clarity with time. Through this sequence a picture in picture montage becomes recognizable, which is presented through Flicker technique.

Peter

Peter

Tscherkassky: ParallelSpace: Inter-View

In a small cadre, which is shown to the audience by the filmmaker where he films himself in the mirror, every frame is alternated with the frame of psychoanalytic furniture. This evokes the impression that the picture is located between the couch and the chair. Following this sequence the autobiographical intention is clarified by zooming on a portrait. Shortly after that the phrase appears: ‘When I got conscious, there was nobody’ followed by the picture of a woman, who looks through a door at the audience. Gabriele Jutz writes with this regard: “not as a body is she present (no body), but as a gaze”(Gabriele Jutz: 2007). The subject of the gaze is presented not only through the picture of the woman, but also through a wall with a window in it. The coming to consciousness, which is announced by the text (‘when I get conscious’), does not succeed in psychoanalysis by the patient through looking at the picture of the mother, for instance. The actual gaze is achieved by looking at the walls and windows of the practice (‘there was nobody’). This reflects the important distinction made in psychoanalysis between the remembered and the imagined. This point signifies a turn in the film, in which various pictures and themes are brought in action, for instance the psychoanalytic encounter with the mother, the family, the time of the Oedipal conflicts, or the sexuality. In this context, we could interpret the picture of the woman as dealing with the symptoms. While we see the picture of a boy, we hear a neurotically interpretable voice (‘you say what mother says…’), where the subject is lead by unconscious motivations. The familial codes comprise an important component of the picture material, which is constantly presented through the triad of mother-father-child and seeks an interpretation thereof. The critics of the Oedipus by Deleuze and Guattari, which are rooted in the object-relation theory of Melanie Klein, point to the societal composition of the unconscious. Tscherkasky succeeds in portraying this criticism by the pictures of Parallel Space: Inter View, which correspond to the typical representations of the Oedipus complex that are made of Found Footage-Material. These pictures of the actor bring forth the intuition of the parent-child scenario. At the same time, they refer to Hollywood, which represents the media culture and the ability to regulate and control the production of desires. It is through this reference to a public that familial limitations are resolved. In other words, the nature of group fantasy is revealed through portrayal of the individual fantasy and the “theatre of representation is transferred back to production of desires...” (Gilles Deleuze, Felix Guattari 1989: 351) The application of ‘found’ material could function as reference to the public aspect of the medium. Before, I go into details about this claim; I would like to discuss the technical and perception relevant aspects of the film, which is necessary for a more intimate understanding of the content of this work.

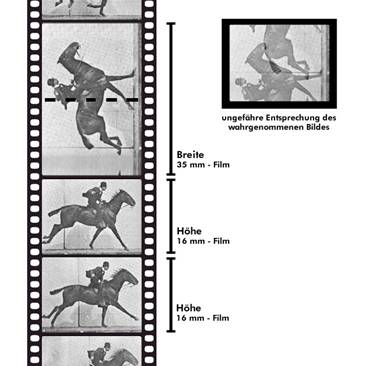

In a conversation with Tscherkasky I found out that he makes a crucial distinction between the order in the optical and the visual. Dream and memory relay pictures out of the inner world of subjectivity. Hence, they are based on the visual representation, which cannot be optically represented in a direct way. The intention of this film, among others, is to take the optical representation and subsume it under a subjective visual regime through the application of the film processes. One of these transformation techniques is the Flicker film technique, which has been partially adopted from the structural films of Peter Kubelka or Paul Sharits and further developed. The 35mm photographs, which originated partially from film pictures, are vertically illuminated on 16mm film stripes. Since the negatives are exactly double so wide as a picture of the small film format, throughout the projection the bottom half or the top half is alternatively presented (see picture 8; ‘film formats’). A location on the picture or film is projected and it is simultaneously divided in two moments. However, the observer experiences this duality as a unity, since the pictures are presented at a speed of 24 frames per second. Moreover the top and the bottom are abstracted under the Flicker technique. The fact that picture parts are composed of isolated cadres becomes surprisingly manifest when the film is stopped during playing. While during play this fact is hidden by Flicker technique. Similarly, in the pictures of dream and memory, which are composed of two pictures, are united as single impression.

This technical setting of uniting of pictures corresponds to the mental process of condensation, which characterizes the primary process of the unconscious mind. Condensation is regulated according to the visual and auditory representability, according to Freud (Joseph Sandler 2003: 136). Through this process various contexts are united into a closed inner representation. The observer tries to recognize each part separately. However, this fails due to the high speed of the presentation of the frames. Inference about individual parts is only possible, when significant correlations between different parts become apparent. Psychoanalysis recognizes the latent meaning of dreams through manifest symbols of dreams.

We arrive at a knowledge of these by dividing the dreams manifest content into ins component parts, without considering any apparent meaning it may have (as a whole), and by then following the associative threats which start from each of what are more isolated elements. These interweave with one another and finally lead to a tissue of thoughts which are not only perfectly rational but can also be easily fitted into the known context of our mutual processes (Sigmund Freund, S.E. Vol. 9: 160)

Parallel Space: Inter-View evokes through the technical setting a gaze, which is the object recognition of the individual pictures. Through generation of correlation between the ‘Flickers’ condensed frames a new sense of meaning emerges. Here, it is not the unconsciousness of the film which becomes manifest. It is more about the position of manifest symbols, which should not be perceived as isolated phenomena but as requirement for the recognition of hidden qualities of an internal unification of separate components. An Inter-View tries actively to see behind the manifest meaning of the pictures and establish the relationships thereof. Throughout this process, the optical presentations of the observer are transformed into visual regiments, which require the intellectual participation of the observer. Refering to Bergson Mauritio Lazzarato follows a similar model in which the optical perceptual model is juxtaposed to simulation technologies: “technologies that simulate formations, which compete against each other in the process of the subject-constitution” (Lazzarato 2002: 95). In Parallel Space: Inter-View the condensation process is not used exclusively for unification of different components of a picture. The film also condenses in a autobiographical journey back to childhood various temporal and spatial moments through Flicker technique: Parents and child, loving and loved objects, window and couch, the couch and the picture of the filmmaker, man and woman, child and baby, which are all instances with psychoanalytic significance. Temporal and symbolic dualities are juxtaposed separately and then presented together again through montage. According to Freud, the processes of unconscious mind are timeless:

They are not ordered temporally, are not altered by the passage of time; they have no reference to time at all. Reference to time is bound up, once again, with the work of the system Cs [Consciousness]. (Sigmund Freud: S.E. Vol. 14, 187)

The combination of various moments of different chronological origin into a condensed picture, which is generated through accelerated projection, corresponds to the Freudian secondary process within the topic model of the mind. Here the unconscious representations, which are temporally unrelated to each other, are condensed and they are treated by the secondary process, where the temporal aspect of the unconscious system functions. Tscherkasskys film simulates those processes, which, according to Freud, deal with the novel presentation of the temporal relationship of condensation in the secondary process. Here, as well, the observer is addressed as an active decoding participant.

Some of the pictures of this work are as negatives presented and compared to the developed pictures. This also provides an avenue for treatment of the relationship between the latent and the manifest memories. Here, the question is posed whether the negative stage of the pictures can be developed freely, or is it subject to censorship. Freud formulated this question in terms of an illustrative example for his theory of mind. Accordingly, “…every psychical act begins as an unconscious one, and it may either remain so or go on developing into consciousness, according as it meets with resistance or not” (Sigmund Freud: S. E. Vol. 12, 264). A movie picture serves in the movie theatre and the production of desires and consciousness. However, it is not essentially of such characteristics. When the negatives and the positives are juxtaposed, then the cultural-industrial process of production of desires and with it the censor function is reflected upon. The negative represents those aspects, which were banned form the production domain, but, nevertheless, succeeded in the conscious production.

The

Repetition

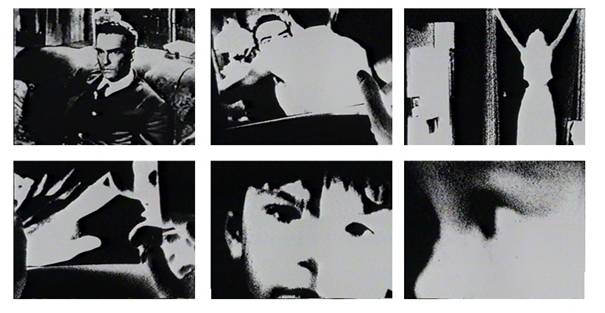

Techniques of Martin Arnolds as film-time

In the following section, we will examine the repetition based presentation of the unconscious in the films of Martin Arnold. His work Piece touchee (1989) was produced by self-built optical printers. Here, an 18 seconds frame of the movie The Human Jungle (1954, director: Joseph M. Newman) is analyzed in terms of movements, where short parts that last few single frames are played in fraction of seconds alternatively in forward and rewind manner. This microscopic method examines and interprets the given material in a novel way and enables a new perspective. Through this process those aspect of the movie, which would go unnoticed in viewing of a typical Hollywood production are brought to the forefront through this process of repetition. This provides the opportunity to examine the manifest meaning in terms of latent meaning of the material. Through repetition and the novel arrangement the details gain a life of their own. The early phase of Martin Arnold’s work with respect to repetition can be distinguished in two types. The first type consists of historical film material, which are imparted a new actuality by appropriation. This is followed by decomposition into smallest possible temporal units, which are played forwards and backwards. The meaning emerges through this second process of repetition is manifested as a differentiation from the original material. This process does not reproduce a copy but an interaction is expressed: the repetition brings forth the difference. The length of the production is extended in order to confront the observer with a new modus of perception through these repetition loops. This process indicates commonalities with the process of bringing into consciousness-repressed material, as postulated by psychoanalytic theory.

Martin Arnold: Piece Touché (1989)

Maurin Turim, who holds Arnolds movies as a meta-commentary to the history of Avant-garde films, maintains in his analysis of the first scene of Piece touché (1989) a relation to the dynamics of the unconscious. I would like to add the following in order to establish the possibility of portrayal of the unconscious mechanism through cinematic medium:

Here the women sits, alone, reading her newspaper, on the right a table with a lamp, on the left, parallel to it, a vase and behind her fauteuil the anteroom/hallway with the closed door. The only thing moving are the fingers of her right hand, absentminded drumming against her left forearm – the slightest of all displacements, a tremor/wince. Yet with the obsessive repetition of alternating cuts, the movie raises this tremor to the frenetic center of attention of the viewer. Her waiting becomes nervous – a tremor, a symptom. (Maureen Turim 1995: 300)

The ‘symptom’ can be understood as the symptom of the fictitious waiting woman in particular, or the general symptom of the film. Through a persisting and repetitive presentation it seems that any Hollywood production can be portrayed in terms of latent symptomatic potentials. For instance, the nervous hand movements at the beginning can be observed simultaneously closing and opening of the ajar door in the background. This process of condensation exposes the latent anxiety of the woman. The tapping of her fingers symbolizes the anxiety of the woman and her expectation that something unpleasant is about to occur. Although, it turns out that a friendly man enters through the door.

Psychoanalysis assumes that the symptoms of the patient repeat themselves in the everyday life of the patient, because an unconscious drive is being repressed continuously. Hence, this repressed drive will manifest itself in different ways in everyday situations instead of being represented in the consciousness.

If the ego, by making use of the signal of unpleasure, attains ist objects of completely surpressing the instinctual impulse, we learn nothing of how this happened. We only find out about it from those cases in which repression must be described as having to a greater or less extent failed. (Sigmund Freud: S. E., Vol. 20, 94)

This function of repression is also of great relevance in the modern theories of psychoanalysis, such as that proposed by Howard Shevrin:

As it is true for manifest dreams (and glosses and associations) in relation to the latent dream thoughts they simultaneously disguise and represent, we must remember that symptoms (and conscious explanations) are displacements; thus, they are more consciously acceptable versions of the underlying conflicts, contents, and fantasies that have remained largely unconscious. (Howard Shevrin 1996: 30)

The repressed drives find substituted expression through displacement, distortion, or suppression. This substituted expression takes the form of a compulsion, which leads to a constant repetition of the symptoms without being noticed by the patient. The analyst becomes aware of this repetitive phenomenon during therapy session and tries subsequently to expose the latent thoughts behind it. At the beginning of the therapy the patient is confronted with an opaque, and hard to decode, ‘message’, which represents the symptom. However, the patient feels this as externally imposed. The goal of the therapy is to enable the patient to take ownership of this ‘message’, which makes it possible for the patient to deal with the disease.

Freud, and psychoanalysts consider the repetition, as an impetus for the patient to revisit the repressed memory continuously. This technique is described as ‘working through’, by which the patient actively confronts the memories. One comes closer to the contents of the unconscious, as it manifests itself, through repetition. This ‘working through’ points to the rhythmic nature of the mental apparatus as well the therapeutic process. In his essay ‘The Uncanny’ Freud portrays his encounter with the phenomenon of repetition during his walk in an Italian city as he continuously finds himself returning unintentionally to a street that is occupied by ‘made-up women’ (Sigmund Freud: S.E. Vol. 17). A walk always takes distractions and never takes the direct path. Therefore, from its essence it is something that harbors the repetition within itself, since it is an expression of the pleasure principle. The pleasure principle leads always the subject within its own psychic organization in a way that the subject constantly feels compelled to perform those actions, which consciously or unconsciously lead to a satisfaction of the pleasure principle. One could think of a film as a path, which runs from a beginning to an end. When a feature of a film is played over and over again, this can function as a continuous return. Normally, in film this serves as style point, which functions as an orientation tool for the audience in order gain a level intimacy with the topic rather than being distracted. Martin Arnold performs this principle through his loop technique to a point that the sense of intimacy is converted into a sense of loss. His early works function not as a direct path, but as a detour.

The mainstream culture, from which Arnold takes his sources, produces a reality with respect to which the desires of subjects develop, for instance, an expression such as dream-factory points to the function of Hollywood. This movement can be analyzed from a film perspective. In the beginning sequences of Pičce touché the man and the woman move to a different location in the room after they have greeted each other ‘extensively’. In the original version, the sequence, in which the man makes a gesture with his hand as he goes ahead, would have been rarely noticed. This movement, through which the man points with his index finger, functions as revealer of the way to be taken. This gesture can give a threatening impression. The extent of this gesture comes to light through persistent repetition of the frames. It becomes apparent the male actor prompts the female figure to act through his hidden gestures. The backplay of the same sequence indicates that the man compels the woman simultaneously to take a seat. Consequently, one can see that the Hollywood film relays latent, hidden, and patriarchal behavior recipes. The symptomatic here is the hidden power relationship within the sexual organization of the gender roles. This pattern can be recognized through a psychoanalytic-like examination modus.

The portrayal, as well as deconstruction, of the family in the Hollywood films is the subject matter of Passage a l’acte (1993), in which a 33 second sequence of the movie To Kill a Mockingbird (1962) made by Robert Mulligan is deconstructed. Again sequences that last approximately 3 to 15 pictures with an alterative speed of 24 frames per second are presented. These frames are played again successively and alternatively forward and backward. The film is dedicated to a criticism of the family situation and the sequence begins with the father voicing an incomprehensible utterance as a result of which the son runs out of the room. This frame lasts about 5 seconds and does not require the usage of a time-manipulating technique. Subsequently, Arnold proceeds, using the loop techniques, to work out the tension in the scene. The father looks at the mother with raised eyes. The mother, in return, makes a small movement, which through further repetition gives the impression as if she would shake as a result of this further filmic repetition. Arnold stays at this sequence for a noticeable 15 seconds. Through this sequence the critical intention of the film, in form of a significant examination of this subject matter, is clarified.

Martin Arnold: Passage á l'acte (1993)

As this sequence further develops, the father raises his brow, to which the mother responds with agreeable nodding that does not give the impression of being the result of a free choice. Moreover, the impression is relayed that gestures of the father demand the gestures of the mother. The patriarchal quality of this sequence would not have been recognized in the original version. This emerges clearly as a result of the analysis. The movie focuses on the details like a microscope. However, it is not a spatial dimension, which is magnified but the temporal dimension. The latent fear of the mother, which is hidden in the manifest version, is recognized. The methodology used by Arnold to reveal these symptoms is the same used in psychoanalysis to ‘work through’. The existing claims and pictures are piece by piece over and over again looked at, through which the internal meaning is revealed. Akira M. Lippit applies this mechanism to the functioning of the memory:

„Like the work of memory, the reworking that passage accomplishes uncovers entirely new movements and gestures within the original footage”. (Akira M. Lippit 1997: 6)

The repetition is accordingly always a reference to the past and might lead to a change of perception thereof. One could certainly also recognize drive-based symptoms in the original version (To Kill A Mockingbird). The repetitive treatment of the film leads to a deepening of the recognition of this resistance within the context of the familial reality of the Hollywood film, which were otherwise rarely noticeable in the original version.

Short sequences are divided into single streams, taken on, abandoned, and newly re-worked. In this process the audience is engaged in a dialog of the pictures and action informed by the deep structures of the work. The modeling process generates a work of art the structure of which indicates commonalities with the psychoanalytic methodology. This is further revealed through subsequent sequence of the movie. As the son enters again through the door, the father indicates to him to take a seat. The hand movements of the father, at first, generate a tapping sound, which through the repetition process is revealed to be more a knocking. After the hand moves upward, it points to the empty chair as the seat to be taken by the son. Arnold, through his analysis, succeeds in showing the nervous character thereof and the symptomatic nature of the whole situation. A certain comical, and childish, element accompanies the father’s hand gesture as if it were toy gun. This impression is magnified by the sound of the closing door. The repetition of this element imparts an impression of a gun shot sound. Here the imposing seriousness of the father is condensed with a certain naiveté as well as reference to violence of gunshots. This condensation generates a joke, which tends to portray a critic of the ruling master relationship that is ‘invited to dance’. The Freudian formulation of the nature of joke, which is treated along with repetition techniques, portrays two different variations of humor in the films of Arnold. One variation is characterized by tendency, while the other lacks any tendency. The pleasure ground of the variation without tendency lies in recognition of the already acquainted. Through the repetitive presentation of the pictures comes into being, as it happens by the repetitive pattern of the joke, a relief of the psychical effort that is perceived as pleasure. Patrizia Giampieri- Deutsch concurs with Freud on this matter and formulates this as relief-pleasure, ‘which through relief of psychic load comes into being’ (Patrizia Giampieri-Deutsch 1998: 65). According to Freud, the same type of pleasure is generated in poetry and arts. In Arnold’s film relief-pleasure is generated through the fact that the pictures from their first appearance are recognizable and subsequently they are repeated. The observer already knows the content after its first appearance. As a result there is no further necessity to generate a psychical load, which would be required to recognize and decode. The slow and stepwise revelation of the novel, and hence the unknown pictures, contains an excitement that avoids the descension of boredom.

After the scene in Passage a l’acte, in which the son was compelled to take a seat, it ensues an argumentative dialog between the siblings. Again, the verbal exchange is temporally manipulated so that it lasts longer. The primary medium of interpretation here for Arnold is the picture and tone. After switching the frames back and forth between the quarreling siblings, Arnold establishes a direct connection between children’s desiring and the parents. This happens as voices of the children, or parts thereof, are being presented in relation to parents. While one could hear the boy uttering ‘come on’, we see the parents. Moreover, since the father is seen to move his mouth during this utterance, we get the impression that it is indeed he is who speaks. This succeeds to illustrate the determinability through the superego, which chooses the claims of the subject determined by the father. The figure of father, or mother, conveys the presence of the whole society and its involvement, such as the father’s boss, the nanny, or the sister. The forcing choice of father is that of the whole community. Žižek maintains that this structure leads to a rejection. The subject finds the subordination under the authority of the name- of-the-father as bad and “thereby the subject ‚yields its desire’ and thus saddles itself with an indelible guilt” (Žižek 1993: 74). This guilt corresponds to the Freudian dis-ease in the culture. Žižek, hereby, also explains Lacan’s theory, in which the subject is reduced to a forced choice and an empty gesture.

Lacans pronouncement states that it is possible for the subject to disengage itself from the oppressiveness/pressure of the super-ego, as it repeats the choices and in that way frees itself from the constitutive guilt. The price is exorbitant. If the first choice is ‘bad’, the repetition in its formal structure is ‘worse’, for it is an act of dissociation from the symbolic community. (Žižek 1993: 76)

For Lacan, the subject can rarely free himself/herself from the symbolizing and repressive real and through which generated repetition compulsion. The subject finds always himself in a simultaneous effort to act against it and yield to it. In contrast, the Freudian theory maintains that subject through the process of therapy adapts to the repressive ground and proceeds consciously to evade the compulsion and deal with it. The quarrel scene in Arnold’s film illustrates the Lacanian variation. The symbolized quarrel between the siblings results in an association of the voice of the son with that of the father. The ‘come on‘ of the son, which refers to the forced choice, appears in the moment when the discussion runs out of control and the ego loses its integrity. Parallel to this sequence, the girl reaches for a cup, which relays an impression to flee. This movement is associated with the mother through a process of acceleration, who sits across the daughter, with a bowed head, and drinks from her cup without uttering a word. This too portrays the symptomatic contained in the scene. The forced choice finds its expression continuously from the father through the son; while the silence finds its manifestation from the mother through the daughter, who does not speak. This is rooted in a continuously present traumatic symptomatic. This repressed symbolization, which is noticed through repetition, gives rise simultaneously through the same repetition to a resistance. Arnold shows via his technique the hidden symptoms of the Hollywood movies, which are brought to consciousness. The aspects, which in the original material were not completely symbolized and in the universe of meaning not integrated, are made for the observer comprehensible through a pulsating rhythm of the picture. This occurs both in strengthening of its repression and intimation for the audience.

As I indicated, we encounter repetition in Freud twofold: on one side, it compels, under the influence of the unconscious, the subject to wrong actions, such as taking detours during a walk. The relationship of the perception to primary function of condensation is rhythmically organized. However, there is repetitive movement in therapy, where the symptom can be acted against through a repetitive movement. The film techniques rely on those structures of the psychoanalytic methodology as well as the constitution of desire. Consequently, there emerges a justified comparable view between film and theory.

References

Akira M., Lippit. 1997. “Martin Arnold’s Memory Machine” in: Afterimage. The Journal of Media Arts and Cultural Criticism. Vol 24 No.6. New York: Rochester.

Aumont , Jacques. 2003. Kurt Kren. „Die Denkfähigkeit der Bilder“ in: Kurt Kren, Das Unbehagen am Film, ed. Thomas Trummer. Trans. Mehrdad Fahramand and Stefanie Diwischek. Wien: Sonderzahl Verlag.

Deleuze , Gilles and Guattari, Felix. 1989. Anti-Ödipus. Kapitalismus und Schizophrenie I. Trans. Mehrdad Fahramand and Stefanie Diwischek. Frankfurt: Suhrkamp.

Freud , Sigmund. Standard Edition [S. E.].

Giampieri-Deutsch , Patrizia. 1998. „Zur Psychoanalyse des schöpferischen Prozesses“ in Schöner Wahnsinn. Beiträge zu Psychoanalyse und Kunst, ed Karl Stockreiter. Trans. Mehrdad Fahramand and Stefanie Diwischek. Wien: Turia und Kant.

Jutz , Gabriele. 2007. „Die Physik des Sehens“. Internet reference: http://www.tscherkassky.at/inhalt/txt_ue/03_jutz.html (accessed 17 May 2007). Trans. Mehrdad Fahramand and Stefanie Diwischek.

Laplanche, Jean. 1999. “The Unconscious. A Psychoanalytic Study” in The Unconscious and the Id., ed. Laplanche, Jean. London: Rebus.

Lorenz , Thorsten. 1987. “Der kinematographische Un-Fall der Seelenkunde“ in Diskursanalysen 1. Medien, eds. F. A. Kittler and others. Trans. Mehrdad Fahramand and Stefanie Diwischek. Berlin: Opladen.

Sandler, Joseph and others. 2003. Freuds Modelle der Seele. Trans. Mehrdad Fahramand and Stefanie Diwischek. Giessen: Psychosozial-Verlag.

Shevrin , Howard, A. O. 1996. Conscious And Unconscious Processes. Psychodynamic, Cognitive and Neurophysiological Convergences. New York: The Guilford Press.

Turim , Maureen. 1995. „Eine Begegnung mit dem Bild – Martin Arnolds ‚pičce touchée’“ in Avantgardefilm – Österreich. 1950 bis heut, eds Alexander Horwath and others. Trans. Mehrdad Fahramand and Stefanie Diwischek. Wien: Wespennest.

Received: July 7, 2008, Published: December 31, 2008. Copyright © 2008 Andreas Fraunberger