Farewell Lucian Freud (1922-2011), Master Painter of the Subjective Body

by

Joseph Dodds

January 17, 2012

Lucian Freud (1922-2011) is widely acknowledged as one of the greatest painters of the second half of the 20th and early 21st centuries, and someone who kept figurative painting alive. Many in the field of psychoanalysis are first drawn to Lucian because of his famous grandfather, but are then captivated by the depth and texture of bodies and their ability to portray the density and inner psychic truth of the individuals painted. The physicality of Lucian Freud's works are intriguing and powerful for anyone interested in the overlapping areas of psychoanalysis and art, mind and body, psyche and soma. This paper functions as a psychoanalytic obituary to a master painter of the subjective body, and explores concepts such as skin, abjection, the body, death and mourning, painting and therapy, as we are drawn in to a cartography of flesh. For both Lucian and Sigmund Freud, transience does not remove the power of life or art, its value or its beauty, and the importance of Lucian Freud’s creative works will endure well beyond the death of its creator.

Farewell Lucian Freud, Master Painter of the Subjective Body (1922-2011) - Joseph Dodds

Lucian Freud died aged 88, at home on July 20th, 2011, his latest painting not yet finished. As well as being the grandson of Sigmund Freud, Lucian Freud is widely acknowledged as one of the greatest painters of the second half of the 20th and early 21st centuries, and someone who kept figurative painting alive at a time when it was unfashionable during the rise and reign of abstract and conceptual art. Like many in the field of psychoanalysis, I was first drawn to Lucian because of his famous grandfather, but was then captivated by the depth and texture of bodies and their ability to portray the density and inner psychic truth of the individuals painted. As someone who is fascinated by the overlapping areas of psychoanalysis and art, and the connections between mind and body, psyche and soma, the physicality of Lucian Freud's works are intriguing and powerful.

Lucian Freud was born in Berlin as the son of the architect Ernst Freud and Lucie Brasch. Ernst Freud was known for both art deco and modern styles, and included amoung other commissions the consulting room for Melanie Klein, and remodeling the house in Hampstead, London which Ernst’s father Sigmund and sister Anna moved into in 1938 (now the Freud Museum). Lucian moved to London with his family to escape Nazism in 1933, and became a naturalized British citizen in 1939. His first solo exhibition was in 1944, and despite brief periods in Paris and Greece, he worked in London until he died.

Lucian Freud was born in Berlin as the son of the architect Ernst Freud and Lucie Brasch. Ernst Freud was known for both art deco and modern styles, and included amoung other commissions the consulting room for Melanie Klein, and remodeling the house in Hampstead, London which Ernst’s father Sigmund and sister Anna moved into in 1938 (now the Freud Museum). Lucian moved to London with his family to escape Nazism in 1933, and became a naturalized British citizen in 1939. His first solo exhibition was in 1944, and despite brief periods in Paris and Greece, he worked in London until he died.

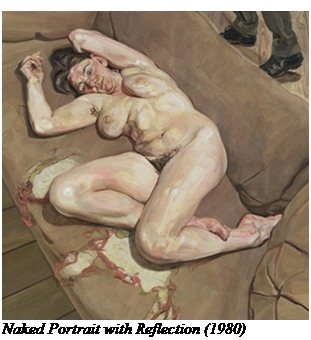

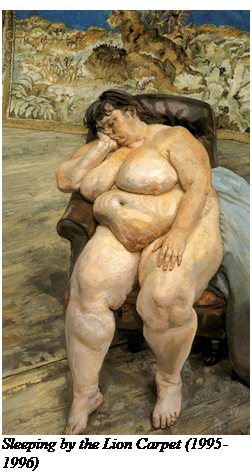

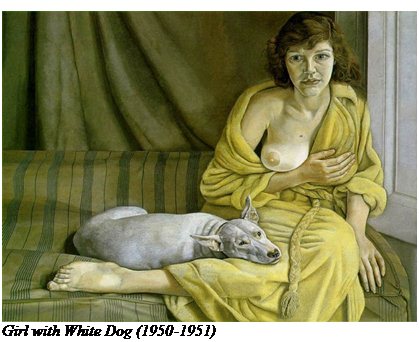

On May 28th, 2011, the Czech Psychoanalytical Society (IPA) hosted a presentation by Rotraut De Clerck on Lucian Freud, entitled ‘How Deep is the Skin? Surface and Depth in Lucian Freud’s Female Nudes’. Many of the ideas De Clerck presented I will be working with internally for some time to come, and they offer one way of dealing with the sadness of his passing. Key ideas from her presentation was the emphasis on the skin as text in Lucian Freud’s nudes, such as Sleeping by the Lion Carpet (1995-96), Naked Girl (1966), Lying by the rags (1989 – 90). These were explored in profound ways through psychoanalytic theories such as psychic skin and the skin ego (Freud 1923, Anzieu 1989), as well as being seen as resisting the postmodern emphasis on surfaces and airbrushed perfection (Butler 1993). Lucian Freud’s portraits evoke and bring to life an inner depth. "I paint people," Freud said, "not because of what they are like, not exactly in spite of what they are like, but how they happen to be."

De Clerck (2011) claims that for Lucian Freud, “the skin is the principal vehicle for the expression of the individuality of the person, more important in this way than is the face”, connecting to “issues of identity in modern society: the place of mental life, of thinking and phantasies, the place of the body, of pleasure and pain, the place of sex and of sexuality...issues of time and space in relation to the physical existence, of death and decay.” While Freud (1923) saw the ego as a mental projection of the surface of the body, De Clerck emphasized the connections between the body, in particular the skin, and wider society and culture. The problems of identity in contemporary society where boundaries no longer seem secure are manifested in attempts to manipulate the skin and body, in self-harm, liposuction, and skin disorders. The scars that mark the fragile individuality of the body, the pain which temporarily revives a sense of aliveness and body boundaries, the skin disorder which embodies the lack of meaning and encapsulates what the mind is not able to hold onto. The skin is where inside and outside, self and society meet.

Lucian Freud’s work can also be explored in relation to Kristeva’s theory of the abject (Dodds 2011b). From the standpoint of the symbolic, the semiotic/pre-Oedipal is a constant disruptive pressure on ordered language (word-play, colour, death, gaps in sense, laughter, unstructured music). The abject is a way of reacting to the encroachment of the semiotic. As the subject is socialised it gradually reject the mother and the corporeal semiotic realm through 'rites of defilement' (toilet training, cleanliness, ritual, taboo, etc.) The clean and proper body excludes the abject, the semiotic, the marginal and what is rejected “constantly exerts pressure on the symbolic order, threatening disruption and reminding the subject of the impossibility of transcending the corporeal origins of subjectivity” (Vice 1996, 153).

In Lucian Freud's portraits of nudes, especially female, there is an evocation of abjection, of the corporeal mother who must be symbollically expelled in order for the subject to come into being. And yet rather than staging a 'rite of defilement', there is a fascination, we are drawn in. The 'glare' of the portraits refers both to the external sources of light reflected on bodily surfaces, and also glare as in look, the stare. The images, at once abject and beautiful, stare back at us, but not from the eyes of its subjects, from the skin itself. We are caught in the gaze of bodies. After first looking away, filled with disgust, there is a return, to the folds, the textures, the touch and smell, the loving portrail of every bump of skin, to a fascination with Freud’s cartography of flesh.

In Lucian Freud's portraits of nudes, especially female, there is an evocation of abjection, of the corporeal mother who must be symbollically expelled in order for the subject to come into being. And yet rather than staging a 'rite of defilement', there is a fascination, we are drawn in. The 'glare' of the portraits refers both to the external sources of light reflected on bodily surfaces, and also glare as in look, the stare. The images, at once abject and beautiful, stare back at us, but not from the eyes of its subjects, from the skin itself. We are caught in the gaze of bodies. After first looking away, filled with disgust, there is a return, to the folds, the textures, the touch and smell, the loving portrail of every bump of skin, to a fascination with Freud’s cartography of flesh.

Lucian Freud uses no fig leaf, as De Clerck pointed out. He paints every part of the body in realistic detail, not excluding the genitals, treating them just as another part of the body. In painting bodies he is painting people, and bodies rather than faces are placed at the centre of psychic life, as his grandfather had done before. De Clerck’s (2011) paper focussed on the emerging of subjectivity in direct contact with the sense of touch, our first archaic sense (Detig-Kohler, 2000), and the move in psychoanalysis from an emphasis on the skin with orifices to the skin as a container of meaning and holding, of protection and boundaries. Anzieu’s (1989) ‘skin-ego’, and its close connection to bodily contact with the primary object, brings a specific sense to our experience of Lucian Freud’s paintings.

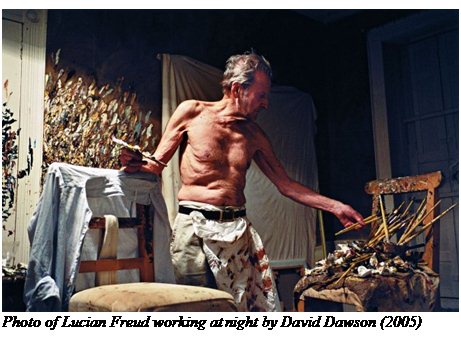

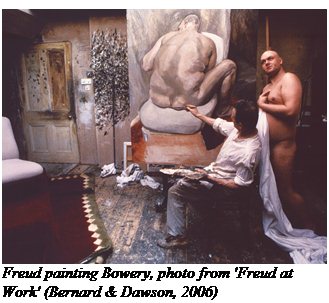

Here it is useful to get a sense of his artistic process. He painted very slowly, spending a huge amount of time with each subject, and demanded the model's presence even while not directly working on the portrait. A nude completed in 2007 (Ria, Naked Portrait) required sixteen months of work, with the model posing all but four evenings during that time; with each session averaging five hours, the painting took around 2,400 hours to complete (Gayford 2007). The level of intensity and depth of this process, and the sheer scale of work and time involved, is perhaps only comparable to a full psychoanalysis. For both Lucian, and those following in the footsteps of his grandfather Sigmund, time and space is required to establish and uncover the inner depths of the individual, to allow the unconscious to speak. The truth of Lucian Freud’s paintings, as beautiful as they are harsh, emerges from hour upon hour of intense engagement with the people he paints. As in psychoanalysis, a rapport with his models is necessary, a painterly version of the ‘therapeutic alliance’. This bond is powerful and exclusive. Lucian Freud says that while he is working on a painting it is important that this is the only painting he is working on. Or more than this that it is the only painting he has ever worked on. And even further as though it is the only painting that has ever been painted.

Freud’s technique usually begins by first drawing in charcoal on the canvas. He then applies paint to a small area of the canvas, and gradually works outward from that point. For a new model he has not yet painted before, Lucian of often starts with the head as a means of "getting to know" the person. He then paints the rest of the figure, returning to the head as his feeling/understanding of the model deepens. One is drawn to the experience of the infant, who gradually gets to know his mothers body and his own. From a focus on part objects such as the breast, and from the mirror of the mothers face (Winnicott), to a gradual awareness of the mother as a whole person, with her own desires, wishes, and suffering, and the connection with the discovery of the infants own body and gradual psychic integration. Freud leaves a section of canvas bare until the painting is finished, reminding that the work is in progress. This brings to mind the work of the great Kleinian psychoanalyst Hanna Segal, who also sadly passed away the same month as Lucian, on July 5th 2011, and her idea (Segal 1981) that works of art are always incomplete, as our own imagination as viewers must “bridge the last gap” through internal contemplation. Segal’s emphasis on the relation of art to mourning and the working through of the depressive position is one of her many important legacies to psychoanalysis and psychoanalytic aesthetics.

Freud’s technique usually begins by first drawing in charcoal on the canvas. He then applies paint to a small area of the canvas, and gradually works outward from that point. For a new model he has not yet painted before, Lucian of often starts with the head as a means of "getting to know" the person. He then paints the rest of the figure, returning to the head as his feeling/understanding of the model deepens. One is drawn to the experience of the infant, who gradually gets to know his mothers body and his own. From a focus on part objects such as the breast, and from the mirror of the mothers face (Winnicott), to a gradual awareness of the mother as a whole person, with her own desires, wishes, and suffering, and the connection with the discovery of the infants own body and gradual psychic integration. Freud leaves a section of canvas bare until the painting is finished, reminding that the work is in progress. This brings to mind the work of the great Kleinian psychoanalyst Hanna Segal, who also sadly passed away the same month as Lucian, on July 5th 2011, and her idea (Segal 1981) that works of art are always incomplete, as our own imagination as viewers must “bridge the last gap” through internal contemplation. Segal’s emphasis on the relation of art to mourning and the working through of the depressive position is one of her many important legacies to psychoanalysis and psychoanalytic aesthetics.

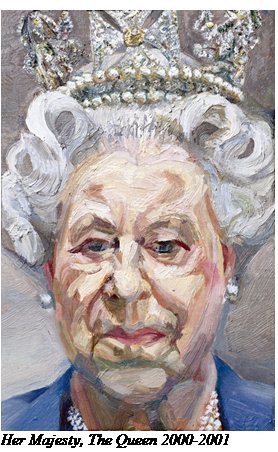

Freud’s final work is an full-spectrum experience, embodying months of intense observation and exploration. Asked when he knows he’s finished, his answer could be also given as one way to answer how we know when a psychoanalysis is finished. For Lucian, he feels a work is finished when he gets the impression of working on somebody else’s painting. As well as painting family and friends, Freud painted those at both ends of the social hierarchy, from aristocracy (including even Her Majesty The Queen2000-01) and the cultural elite including fellow painters such as David Hockney, to paintings such as those of the obese benefits supervisor Sue Tilleym, which includes the most any painting by a living artist has ever sold for (Benefits Supervisor Sleeping, oil on canvas 1995, which sold for $33.6 million.) Freud also loved painting animals, either on their own (especially horses), or in intimate relations to human subjects (such as Naked Man with rat,1977-78). In fact his portraits of animals show at times a greater level of sympathy then some of his human subjects (Auerbach 2004), and can be usefully explored as a study of the psychology of human-animal relations (Dodds 2011a).

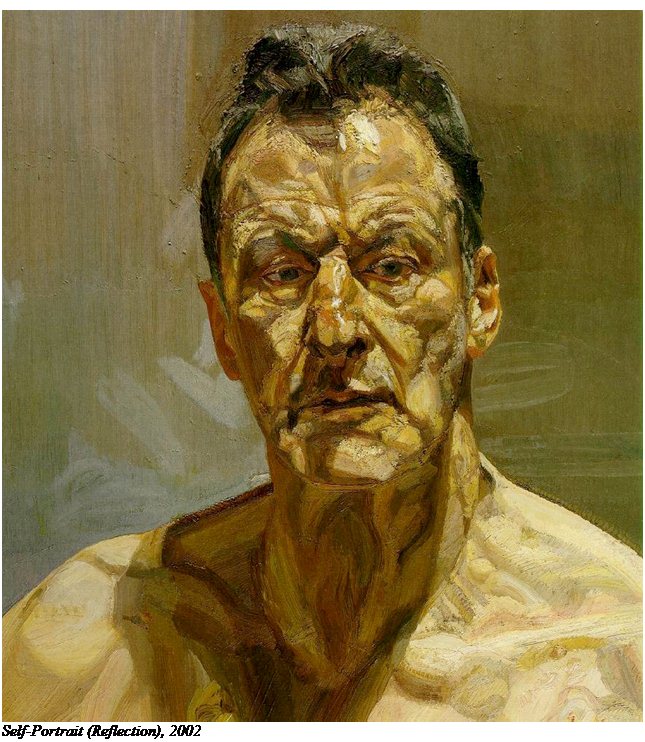

Lucian Freud painted until the end, and his self-portraits such as for instance Reflection (Self-portrait) (1985), Painter working Reflection (1993), Self-Portrait (Reflection) (2002) are perhaps the most evocative at this moment. Lucian once said that self-portraits are the most tempting to do because the subject is always ready to hand, but that he both starts and destroys more self-portraits than any other, because they so often ‘go wrong’. In a documentary interviewing his subjects (Auerbach 2004), his children (who have been painted frequently by Lucian, and was a crucial ways in which they were able to maintain a relationship with their father) expressed amazement that he is able to see himself in this way, with such unflinching stark honesty. In addition they expressed a sadness, as each self-portrait clearly documents the inevitable march of their father towards his appointment with death.

According to De Clerck, the shock of the nakedness in Lucian Freud’s paintings owe as much to death as sexuality, Eros and Thanatos, and we can also see the dialectic discussed by Winnicott, the desire to both hide but yet reveal, the deep fear and simultaneous intense longing to be found. From Lucian’s difficult childhood involving a flight to England to escape Nazi persecution, through his long, productive and creative life, Lucian engaged in a struggle with the difficult truths of existence with an authenticity and truthfulness which reminds us of the spirit of his grandfather, and yet he has undoubtedly carved out a unique place for himself in his contributions to the culture and humanity. In Freud’s paintings, we are faced with reality of ourselves, own sexuality, our aging bodies: “Freud’s paintings do not allow distancing, they leave no space for it, make us feel our own bodies, trapped in a skin that will record the imprints of our life.” They force us to face the reality of our own bodies, what in Lacanian terms might be called the ‘real’ body as opposed to the ‘imaginary body’ of the glossy artificially smoothed image (which we attempt to recapture through our own gaze at our mirror reflection, where we hold our stomach in, try to find the best angle, etc). or the 'symbolic body' of cultural texts.

According to De Clerck, the shock of the nakedness in Lucian Freud’s paintings owe as much to death as sexuality, Eros and Thanatos, and we can also see the dialectic discussed by Winnicott, the desire to both hide but yet reveal, the deep fear and simultaneous intense longing to be found. From Lucian’s difficult childhood involving a flight to England to escape Nazi persecution, through his long, productive and creative life, Lucian engaged in a struggle with the difficult truths of existence with an authenticity and truthfulness which reminds us of the spirit of his grandfather, and yet he has undoubtedly carved out a unique place for himself in his contributions to the culture and humanity. In Freud’s paintings, we are faced with reality of ourselves, own sexuality, our aging bodies: “Freud’s paintings do not allow distancing, they leave no space for it, make us feel our own bodies, trapped in a skin that will record the imprints of our life.” They force us to face the reality of our own bodies, what in Lacanian terms might be called the ‘real’ body as opposed to the ‘imaginary body’ of the glossy artificially smoothed image (which we attempt to recapture through our own gaze at our mirror reflection, where we hold our stomach in, try to find the best angle, etc). or the 'symbolic body' of cultural texts.

Instead we have flesh, and folds. A skin with history, with a memory, and above all with an irreversible entropic direction, as it heads towards its material destiny of the corpse. De Clerck suggests we look at the move in Lucian Freud’s work from a sense of skin as fragile and almost see-through in paintings such as Girl with leaves (1948) or Man with a feather (1943), to the skin as encasement, and carapace, through the psychoanalytic ideas the ‘thin-skinned’ and ‘thick-skinned’ narcissitic syndromes (Rosenfeld 1987), and connect this to the shift in the painter’s own life and trauma.

As Lucian’s grandfather quoted in one paper, ‘though owest nature a death’. As dead skin and excreta are abjected from the body so that I might live, at the end the body itself, I, am abjected. The thick skin, and thick paint, are perhaps both a protection from this fate, and its premature actuality. This reminds us of Sigmund Freud’s beautiful paper ‘On Transience’ with its important concept of anticipatory mourning. For Rilke, who many identify as the nameless poet in Freud's essay, knowledge that a flower is temporary, that it will fade, die, and rot, removes the beauty it still has while it is alive. For both Lucian and Sigmund Freud, this transience does not remove the power of life or art, its value or its beauty, and the importance of Lucian Freud’s creative works will endure well beyond the death of its creator. Perhaps, at this moment, the painting which best captures the spirit of the man who has just past away, is his self-portrait from 2002, a ‘reflection’ as he called it, a reflection of an extraordinary artist.

- Joseph Dodds, University of New York in Prague, dodds@psychoanalyza.cz.

Based on a paper read to the Czech Psychoanalysis Society on May 28th 2011, 'Confronting the Abject: Reflections on Rotraut De Clerck’s (2011) “How deep is the skin? Surface and Depth in Lucian Freud´s Female Nudes” ' (Dodds 2011b).

References

Anzieu, D. (1989) The Skin Ego, New Haven, Yale Univ. Press

Auerbach, J. (2004) Lucian Freud: Portraits (television documentary).

Bateman, N (2006) Freud at work. Lucian Freud in Conversation with Sebastian Smee, London, Jonathan Cape, Random House.

Bernard, B. and Dawson, D. (2006) Freud at Work: Lucian Freud in Conversation with Sebastian Smee. Knopf

Butler, J (1993). Bodies that Matter. New York, NY: Routledge.

De Clerck, R. (2011) “How deep is the skin? Surface and Depth in Lucian Freud´s Female Nudes.” Presentation to the Czech Psychoanalytical Society, May 28th, 2011

Detig - Kohler, C (2000). Hautnah: Im psychoanalytischen Dialog mit Hautkranken [Skintight: A psychoanalytical dialogue with sufferers of dermatological illnesses]. Giessen: Psychosozial-Verlag.

Dodds, J. (2011a) Psychoanalysis and Ecology at the Edge of Chaos: Complexity theory, Deleuze|Guattari, and psychoanalysis for a climate in crisis. Routledge

Dodds, J. (2011b) Confronting the Abject: Reflections on Rotraut De Clerck’s “How deep is the skin? Surface and Depth in Lucian Freud´s Female Nudes.” Discussion paper, Czech Psychoanalytical Society, May 28th, 2011

Freud, S. (1923). The ego and the id. SE 19

(1916) On transience. SE 14

Gayford, M. (2007) Lucian Freud: marathon man: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/3668104/Lucian-Freud-marathon-man.html

Rosenfeld, H.(1987) Impasse and Interpretation. Therapeutic and anti-therapeutoc factors in psychoanalysis. London: Tavistock.

Segal, H. (1986) A Psychoanalytic Approach to Aesthetics, in The Work of Hanna Segal: A Kleinian Approach to Clinical Practice Jason Aronson. Free Associations, 1986.

Vice, S. (1996) Psychoanalytic Criticism: A Reader. Polity

Received: January 16, 2012, Published: January 17, 2012. Copyright © 2012 Joseph Dodds